After my stroke, I didn't want to be the miracle girl in the wheelchair

When I was 26, out of the blue, I suffered a massive brain stem stroke caused by an arteriovenous malformation, or AVM, a rare congenital tangle of blood vessels of which I had no warning or symptoms. The malformation surrounded my brainstem and filled my cerebellum, over half of which would be removed in a life-saving brain surgery that took place in the hours following my stroke. What’s more, my AVM contained four aneurysms and was the largest the UCLA neurosurgeon on call had ever seen. He told my husband, who held our sleeping 6-month-old baby in the emergency room's waiting area, that I would likely not survive the day.

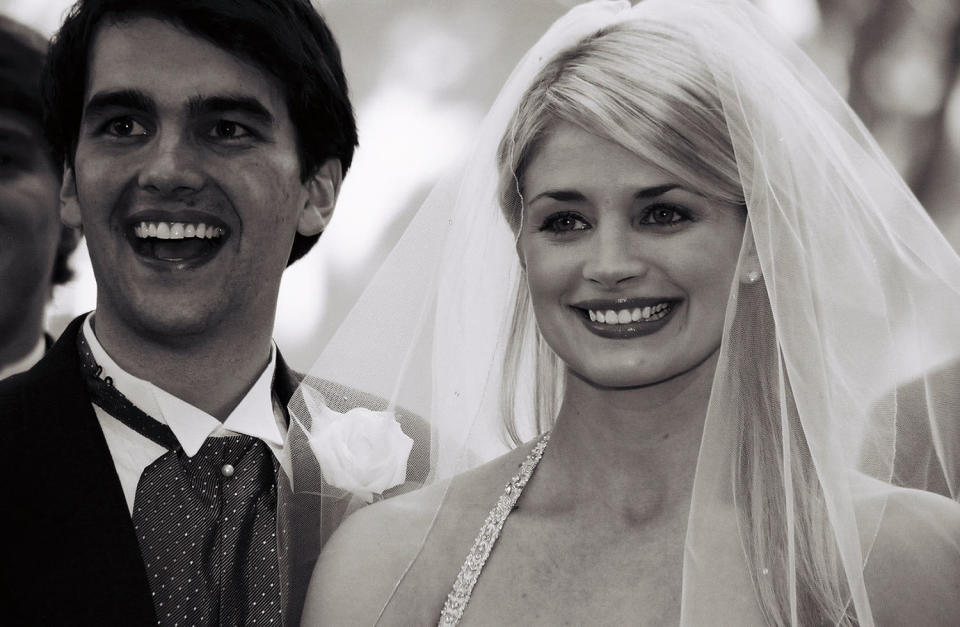

I did survive the day, and I have now lived 16 years of second-chance life. I spent 40 days in the intensive care unit on life support and another year and a half in inpatient brain rehab. I was living with whiplash from the complete upheaval of my reality. In the blink of an eye — or really, the bursting of a blood vessel — my life of blissful new motherhood and steady modeling gigs and California sunshine was leveled to nearly nothing.

Through years of excruciating effort, I relearned to walk, talk and eat. I was hitting all these milestones in pace with my son, actually. Even to this day, those fundamental abilities are nothing like they used to be. Thirteen surgeries, a broken leg, unrelated brain issues later, and a host of deficits remain. From deafness to double vision, facial paralysis to lack of fine motor skills, impaired balance to muscle coordination, my disabilities mean communicating is different, walking is difficult, and driving is altogether out of the question. Yet since my stroke, I have had another biological baby and, with the help of my husband, I share my story and the lessons we’ve learned as a speaker and advocate for other people with disabilities.

As a girl, my favorite pastime was giving inspirational speeches about hope and justice to a captive audience of dolls in my closet. I quoted Martin Luther King Jr. and Holocaust activist Corrie ten Boom until my mom called me to dinner. Even at a young age, I knew I wanted to help people. But in the early days of my new normal, I found myself distraught at the notion I would now be the miracle girl in the wheelchair. I could not wrap my mind around identifying as a bonafide member of a disenfranchised population, rather than just an outside ally and encourager.

Only when my husband and I were asked to speak at a camp for families affected by disabilities did that wounded paradigm start to shift and heal. At the camp, we heard stories of campers whose lives would never be the same after their spouse had an accident or their child was born with a genetic condition or they were diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. We were the speakers, but we could have been the campers. These were our people. They uniquely understood what it felt like to navigate a world not made for them. I felt a new and electrifying call on my life to do what I had been doing since I was a little girl: encourage and advocate for the hurting, but this time, I’d do it from the inside.

Seeing the world from the vantage point of a wheelchair has been eye-opening and shocking. I am now living in a world that’s not made for me. The inaccessibility of public spaces and the thoughtlessness of much of the general population when it comes to disability have been painful but also intensely motivating. And yet if a person with actual disabilities, like myself, had difficulty associating herself with the story of disability, how much more so would the typically abled community?

From the beginning of my speaking career as a woman with disabilities, I’ve attempted to connect with my majority non-disabled audience by opening each talk with this provocative statement: “We are ALL disabled.” At first the audience might bristle or be confused by this claim, until I continue. “Some of us sit in physical wheelchairs, but we all have invisible wheelchairs inside.” Then I often recite a litany of experiences that probably resonate with every member of the audience: “Who among us feels truly free, even when she can walk and drive on her own? Who feels fully beautiful and desired, even when her face is not paralyzed? Who feels heard and understood, even without a speech impairment and deaf ear?” The answer is a resounding and rhetorical NO ONE. We are all disabled. And thus, we need each other.

In my experience, that simple reframing has been the key to taking an inspirational story and making it a personal one. It has invited a non-disabled audience to look at their lives through a new lens and consider how every person is situated on the same spectrum of limitation, rather than in the black-and-white of disabled or abled. The typically abled majority will never effect lasting change for the minority until they see themselves in their story. Our struggles, whether obvious or invisible, do not have to end in isolation but rather can be the beginning of true connection.

In theory, the universalizing of disability might seem to dilute the hardship of living with a disability. In practice, we’ve found the opposite to be true. Just three years later, we were given the opportunity to take ownership of that camp for families with disabilities where we were once the speakers, the camp where our perspective changed so dramatically. And instead of inviting only individuals with disabilities or people with one type of diagnosis to create this community, we invited entire family systems experiencing any kind of disability to find rest, resources and relationships there. Last year alone, 80 different kinds of disabilities were represented among our campers, who ranged from newborn to 78 years old. When we connected over our struggles and shared the hard stuff, we gained new perspectives. We realized “Well, if they can do it, maybe I can too.”

I don’t own the story of loss and marginalization and disappointment. It can belong to all of us. In fact, it’s a better story when it belongs to all of us because then we believe more fully that the story is not over yet.

While I’m giving all my talking points away, I might as well tell you another: “We ALL have a seat at this table together, but some of you will need to hold the door open so others of us can wheel into the room!” If the disabled and typically abled communities agree to both mindfully extend and graciously accept the invitation to the communal table, we will gain things we desperately need but couldn’t find on our own. An untapped healing and an unstoppable hope. A newfound knowledge that we’re not alone. A slower pace at which to move through the world. A vulnerable space to tell our stories and listen intently to others. An embodied practice of looking into the eyes of a stranger and seeing ourselves reflected back. And in doing so, we can deny the lie that the good experience and the hard experience belong to two different groups.

Today, I could not feel more grateful for my place in life, my seat in this wheelchair. Losing nearly everything I thought was important has redefined what goodness, freedom and purpose mean to me. There was a time when I didn’t want to belong to the disability community, but now there’s no identity I’d rather have.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com