How to Stretch Your Fashion Dollar for the Greater Good

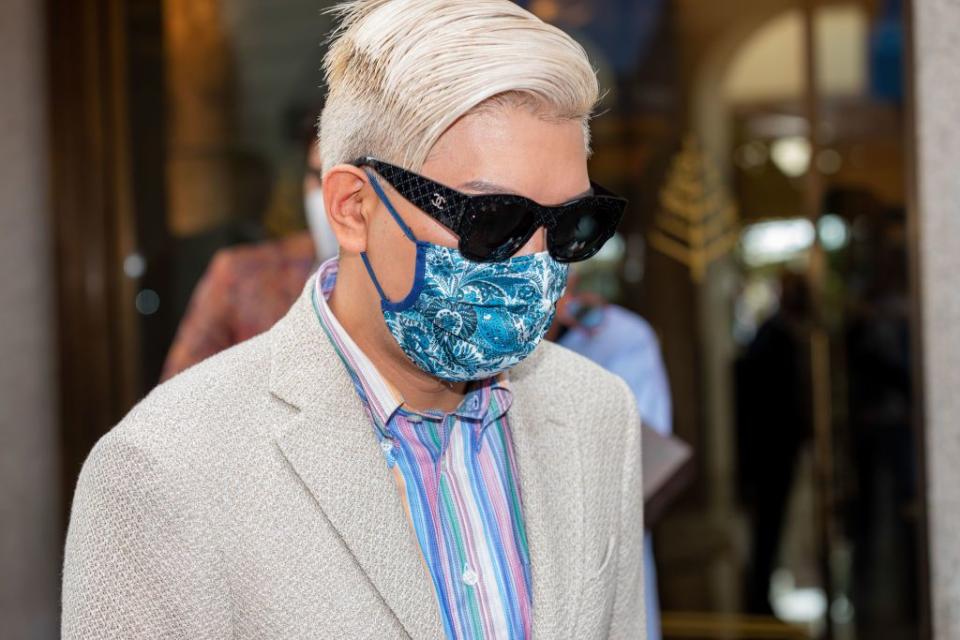

Bryan Grey Yambao, better known by his nom de internet, Bryanboy, made his last big haul in Paris at the start of the year: two Chanel jackets, a few Hermès bags, eight pairs of shoes from various designers, and “Saint Laurent everything.” He tends to do his seasonal shopping mostly during fashion week, as the new collections hit stores, adding something here or there in between.

Nearly every aspect of public life has been upended since then, and now, as shoppers begin to dip their Prada flat–clad toes back into real life after a long lockdown, Yambao, 38, finds himself feeling an uncharacteristic restraint.

“Anything you put on your body is a statement,” he says.

Set against the background of a global pandemic, a social justice reckoning, an ongoing environmental crisis, and a volatile presidential campaign, the new fall season brings a set of tricky questions for luxury buyers that have always been brooding under the surface but only recently struck a nerve: Are you well versed in a brand’s sustainability practices? How about its diversity initiatives? Do you keep up with the founder’s political donations?

From Rodeo Drive to Madison Avenue to Via Monte Napoleone, retail’s main thoroughfares are littered with landmines, and the wrong move can leave the casual shopper not with a status symbol but with a scarlet letter. Wearing current-season designer was once enough to telegraph taste, status, and access. But was shopping ever really all that innocent, or was it always a hidden Rorschach test of our values?

“Fashion has been a tool to communicate who I am, where I’m from, how I see the world, and my hopes for how I want the world to be,” says Aurora James, the founder and creative director of the accessories label Brother Vellies. It was with that credo in mind that this summer she launched the 15 Percent Pledge, a campaign that asks retailers to procure at least 15 percent of their stock from Black-owned businesses.

“Everyone needs to take a look at what’s important to them. For me that’s female-owned, minority businesses and sustainability,” she says, likening the idea to the way many people favor locally grown produce and farmers markets over big box brands and chain grocery stores. “This is about asking people to look a little harder, beyond the typical channels.”

Fashion, an industry built on ideas of exclusivity, is not usually inclined to introspection. As in every other bottom line–driven business, its players are perfectly willing to look the other way as long as buzz is hot and sales swift. But its fissures, in areas ranging from representation to appropriation, have always been hiding in plain sight.

In his memoir, The Chiffon Trenches, André Leon Talley recalls strolling on Avenue Montaigne with Diane von Furstenberg in the 1970s and hearing the comments of the Parisians: “Look, it’s Princess Diane von Furstenberg with her friend the African king.” In the 1990s, when Jean Paul Gaultier raised eyebrows with a collection he dubbed “Chic Rabbis,” he wasn’t called insensitive—he was hailed as an enfant terrible.

“There was a previous point in history when people would say, ‘Can we just not talk about it?’ ” says the longtime communications strategist Bonnie Morrison. “People now realize, with these demonstrations and protests, that they have a lot of agency. They’ve begun thinking where that spending can be an act of solidarity.”

This year may be an inflection point. An overdue injection of accountability is being brought to the fashion industry by such groups as the Black in Fashion Council and the Kelly Initiative, which is named after the late designer Patrick Kelly and calls on luxury brands to hire more Black talent. It is led by the stylist Jason Campbell, the creative director Henrietta Gallina, and the journalist Kibwe Chase-Marshall. There are also petitions like James’s and social media muckrakers such as the Instagram account Diet Prada. By and large, true influencers, the leaders of globe-spanning behemoths, are paying attention and adapting accordingly. They know that good politics is also good business. Sephora, the beauty giant owned by LVMH, was the first to commit to James’s pledge.

“Luxury shoppers, particularly Gen Z and millennial ones, are increasingly dropping brands based on campaigns or missteps that don’t uphold their values,” says Emma Chiu, global director of the innovation group at Wunderman Thompson. These are socially fluid generations with an expansive vision of what can or should be deemed stylish, cool, and beautiful.

More than advertising campaigns or celebrity adjacencies, ethics are increasingly part of the calculus plugged-in consumers make before untying their purse strings. In this environment, veterans like Stella McCartney, who has long championed animal-friendly and sustainable practices in luxury, and upstarts like Telfar Clemens, who grew his namesake business on the basis of egalitarian design, have an immediate leg up. Which is why Clemens’s Bushwick Birkin is no longer ubiquitous just in Brooklyn.

“The method of shopping has not changed for me, but the perception and execution of responsible luxury consumption has,” says Christine Chiu (no relation to Emma), a Los Angeles–based business-woman, philanthropist, and couture collector. “What has changed is the deepening realization that the value of my luxury shopping dollar can go much further and can do exponentially more good beyond the purchase of the physical item.”

When fashion megahouses, from Kering to Ralph Lauren and beyond, used their resources to help coronavirus relief efforts earlier this year, the message trickled down to clients like Chiu, who saw their largesse as a call to action. “This was a great incentive and a new challenge for me,” she says. “How can I stretch my fashion dollar for the greater good?”

After the great reset, perceptions of luxury may start to look very different, if they haven’t already. From Silver Lake to Shelter Island to Shanghai, no one wants to be out of step with current fashions.

“The thought of running through Erewhon Market in platform Louboutins and a crocodile handbag,” Chiu says, “is very much a thing of 2019.”

The question is how long that renewed consciousness will stay front and center. Yambao, for one, is gravitating less to buzzy, of-the-moment items than to things one might call investment pieces. “You know, clothes that have a longevity,” he says from Sweden, where he’s based, “as opposed to some trendy thing.”

Regardless of the churn of social and geopolitical drama, some things stay the same, pandemics and recessions be damned.

“It’s a running joke with my friends that if we run out of cash, we can just sell our clothes,” Yambao says, laughing. “When you buy an Hermès bag, its value triples the second you walk out the door.”

This story appears in the September 2020 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like