'Streaming stole my record money': why Spotify is ruining rock

Two events in the music world this week have highlighted a curious and complicated schism behind-the-scenes of a multi-billion pound industry. And battle lines are being drawn for an almighty skirmish.

The first event was the purchase by Universal Music of Bob Dylan’s entire back catalogue of 600 songs for a reported $300 million (£225 million). The acquisition, announced on Monday, has been described as the publishing deal of the century and is symptomatic of the monumental sums of money currently being spent by investors to snap up artists’ publishing catalogues.

The billions of pounds these investment companies spend hoovering up songs allows them to collect revenue and royalties every time the song is streamed, sold or played in a shop. As moneymaking instruments, songs are red hot. Last week Fleetwood Mac singer Stevie Nicks sold a majority stake in her publishing catalogue to publisher Primary Wave for $100 million, while in November the publishing rights to Taylor Swift’s first six albums were sold to private equity group Shamrock Holdings for $300 million. Following the Dylan deal, singer-songwriter David Crosby revealed that he was also planning to sell off his song catalogue. "I can’t work," he tweeted, "and streaming stole my record money.”

The second event is the ongoing inquiry into the economics of streaming by the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee in the House of Commons, to which Chic’s Nile Rodgers gave evidence on Tuesday. The probe paints an altogether less baroque picture of the music industry. We all know how convenient music streaming is. That’s a given. But the inquiry heard that eight out of 10 songwriters earn less than £200 a year from streaming.

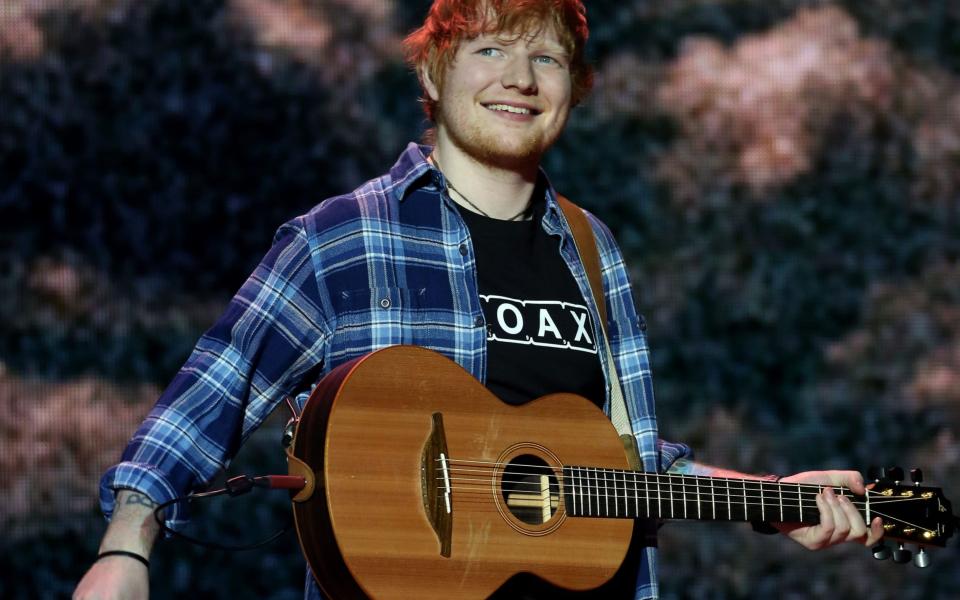

Artists and writers simply do not get their share of the pie (often less than £200 a year), Rodgers told MPs, despite the “staggering” amount of money in the industry. Songwriter Fiona Bevan, who has co-written songs with Ed Sheeran and Kylie Minogue, described the situation as “shameful” and said songwriters have been forced into the (no pun intended) gig economy. “Right now, hit songwriters are driving Ubers,” Bevan said. Jazz saxophonist Soweto Kinch described the situation as a “market failure”.

The musicians' comments follow similar remarks made to the committee last week by Elbow singer Guy Garvey. He said that artists’ lack of money is threatening the very future of music. “That sounds very dramatic,” Garvey said, “but if musicians can’t afford to pay the rent, if they can’t afford to live, we haven’t got tomorrow’s music in place.” Meanwhile Tom Gray, a member of Gomez and the man whose Broken Record alliance helped bring about the inquiry in the first place, tells me that streaming’s meteoric rise is creating a ticking “time bomb” that will decimate grass roots music if nothing changes.

So what’s going on? Why have we got mega-bucks deals on the one hand and musicians prophesying poverty and doom on the other? Can one industry really be so ludicrously lopsided? Well, yes it can. And what’s intriguing is that the feast and the famine both stem from precisely the same source: the business models adopted by Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music and other streaming platforms.

The music industry has entered a new golden age. Streaming – whereby people listen to unlimited music through a desktop or smartphone app for a monthly fee rather than buy the songs as physical copies or downloads – has become the dominant form of music consumption. Investment bank Goldman Sachs predicted in May that the number of paying streaming subscribers around the world will increase from 416 million this year to 1.22 billion by 2030. Streaming revenues will roughly double. And because songs yield royalties to their owners, this vast predicted growth has turned songs into a valuable asset class. The London-listed Hipgnosis Songs Fund, for example, has spent £1.2 billion buying 117 catalogues to date, including songs by Mark Ronson, Justin Bieber and Camila Cabello.

Been getting a lot of questions about the recent sale of my old masters. I hope this clears things up. pic.twitter.com/sscKXp2ibD

— Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) November 16, 2020

So owners of prime catalogues can watch the money roll in. The problem is, however, that songwriters who aren’t Dylan, Sheeran, or Beyoncé (in other words, most of them) don’t make enough money from streaming. Bevan told the Commons inquiry that she co-wrote a track on a recent UK number one album, which was also the fastest selling solo album of the year (the song is thought to be Unstoppable on Kylie Minogue’s Disco album, although Bevan didn’t specify). That track has earned her just £100.

Even Rodgers, who has written, produced or performed on albums that have sold over 500 million copies and also co-founded Hipgnosis, believes that the way streaming is valued is opaque and disadvantageous to the artist. He said he was “completely shocked” at how little streaming platforms pay out. This comes, he says, despite the huge amount of money sloshing around the music industry. “I look at the record labels as my partners, and the interesting thing about my partners is that every time I have audited [them] I find money. Every time. We absolutely must have transparency… Sometimes it’s staggering, the amount of money,” Rodgers told MPs.

Songwriters’ and musicians’ relationships with streaming services are hobbled in a number of ways. Firstly there is the opacity that Rodgers talks about. The contract between an artist and their record company, and the licensing agreements between those record companies and the streaming services, are bound by strict Non-Disclosure Agreements and contain all sorts of old fashioned and obscure clauses, making meaningful analysis of what songwriters actually own very difficult.

Then there’s the slice of the pie that they officially get: of a subscriber’s £10 monthly fee, £3 goes to the streaming service, £5.50 goes to the record label, and £1.50 goes to the songwriter or the publisher. The record label and the publisher then take their cuts and pass on the rest to the artist or writer. The fact that the writers get just 15 per cent (or a cut of 15 per cent) is the cause of much frustration. (Not to mention that there are usually multiple writers on a song, and they must share that 15 per cent between them.)

There’s a reason for this. When a song is broadcast in a shop or on the radio, half the royalties goes to the artist and half goes to the record label. It is known as Equitable Remuneration as the money is split equally. But streaming services treat the playing of a song as they would a sale. And under copyright law, sales are not subject to Equitable Remuneration, meaning the labels take a bigger cut. Rodgers told the Commons that a music stream should be treated as a license rather than a sale, which makes sense anyway as listeners don’t technically own it.

A further hobbling factor is the way that services such as Spotify divvy up the money under the so-called Revenue Share Model. The way it works is that Spotify takes all the monthly money from all subscribers and then pays it out proportionately based on the total spread of streams listened to. So a middling artist who gets, say, 30,000 listens in a month won’t get paid for each of those 30,000 listens.

Rather their payment will depend on the percentage of the total number of songs listened to that their 30,000 accounts for. Which, at a time when the likes of Dua Lipa can get over a billion streams for a single song, won’t be much. Broken Record’s Gray and others are called for the model to change to a so-called Usercentric model under which artists are paid as a proportion of an individual user’s listening habits. So, to use a simplistic example, if I spent a month listening exclusively to Gomez, then that band would get all of the £7 of my subscription that Spotify pays out.

So why aren’t record labels and streaming services doing anything about this? A cynic would say it’s because there’s so much money rolling in. Warner Music Group, one of the big three remaining record companies which floated on the US stock market in the summer, has paid its shareholders dividends of $120 million in recent months. And Universal, another of the big three, is gearing up for its own IPO. As Rodgers says, there is a huge amount of money out there.

Which takes us back to the heady valuations of music catalogues. Rodgers told the Commons that this is a good thing as songs are finally being properly managed and monetised. The hope is that songs’ stock will continue to rise, causing money to trickle down to songwriters. The boss of one big music publishing company tells me he thinks songs are still undervalued. “One of the things that I hope will come out of this DCMS inquiry is that we’ll get an increased share of the cake,” he says.

We’ve been here before. The music industry has a track record of getting things wrong, almost always in the wake of a new technology coming along. After the phonograph and gramophone (or ‘talking machines’ as they were delightfully known) were first invented at the end of the nineteenth century, dozens of manufacturers piled in trying to make a quick buck. Outlandish and expensive models included a quadruple turntable vertically-stacked gramophone capable of playing all four parts of a quartet at the same time and a gramophone disguised as a finely coopered beer barrel.

Things only took off when a price war forced down the cost of records and machines to levels acceptable to the public. And the CD boom of the 1980s and 1990s saw record companies milk this cash cow for all it was worth. But they set prices so high that they drove consumers to piracy via platforms such as Napster, which led to an industry-wide reckoning. Some would argue that these are analogous to the current situation regarding streaming. Different decade, same groove.

So how does this current situation play out? Under the worst-case scenario outlined by Gray, the house of cards could collapse and leave a career in music as an unviable option for future generations. “The music industry are creating a time bomb for themselves, and it’s born out of a combination of short-termism and corporate inertia. They are defunding most of music,” he says.

Rodgers has a more palatable solution. He says that record labels know that the streaming revolution is going to net them “astronomical” amounts of money in the years ahead. Safe in this knowledge, now is the time to pay songwriters more.

“Right now we have a situation that is so financially viable and the future is so clear. We are a family. Let’s sit down. Let’s be fair. Everybody is not going to be Ed Sheeran and everybody is not going to be Dua. That’s just the reality. Even Dua won’t be Dua soon… But it’s OK. We love being in this business. And if we have a fair and equitable business we can get through the hard times as well as enjoying the great times.”

Rodgers remains hopeful that the industry can change its tune. “We have never had a better time to deal with this issue.”