A story we don't tell 'thoroughly enough': Meg Kissinger shares her family's mental health struggles

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Meg Kissinger's reporting on the broken Milwaukee County mental health care system led to public policy changes, including the creation of supportive housing for people with severe mental illness.

Now Kissinger has turned her dogged empathy to telling the story of her own family's mental health crises.

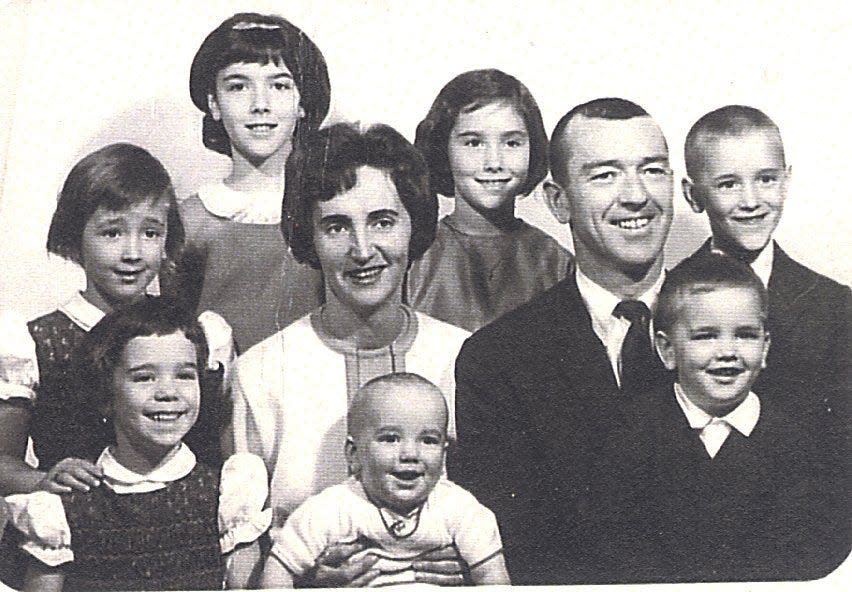

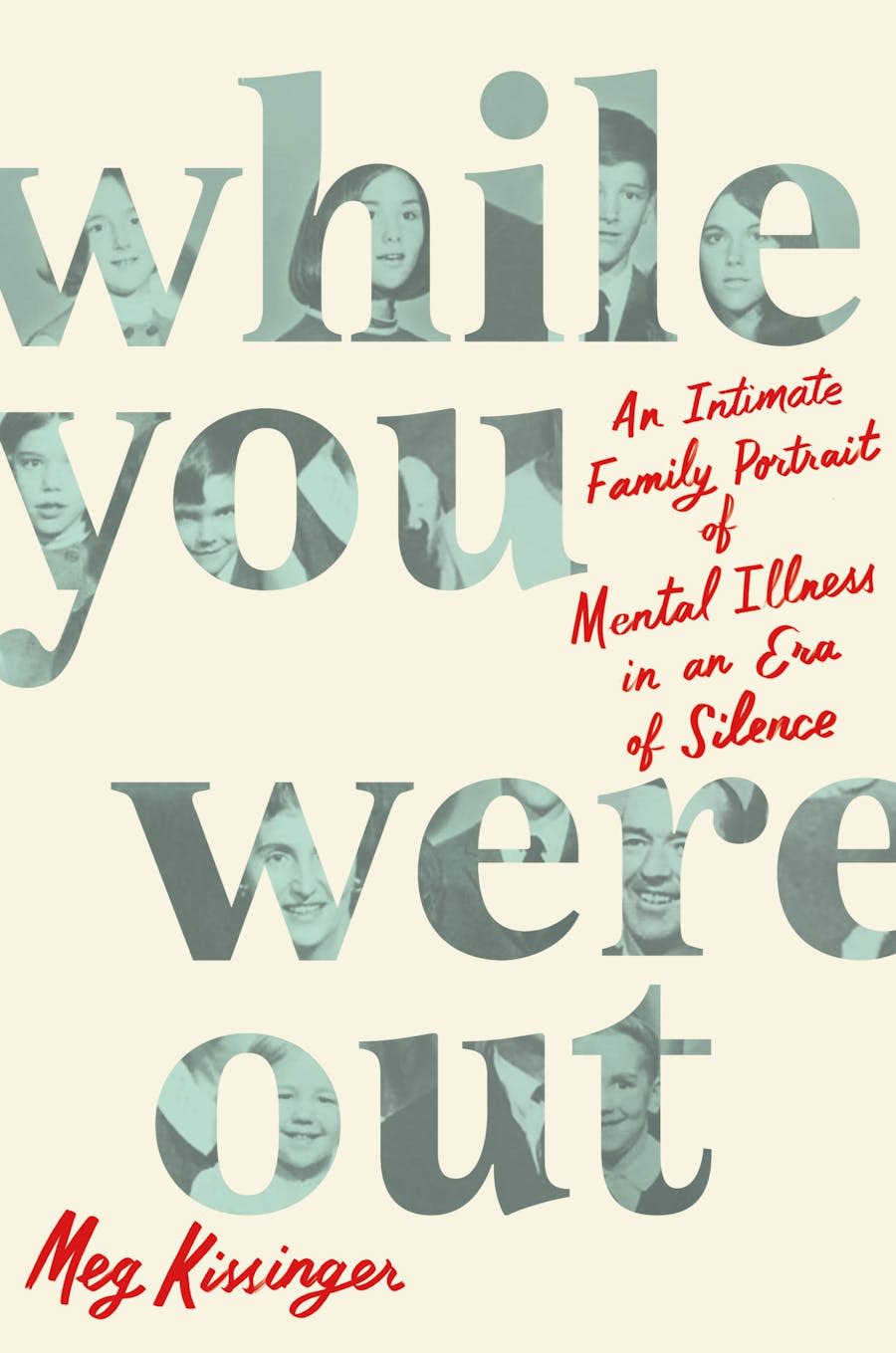

As depicted in her new book "While You Were Out: An Intimate Family Portrait of Mental Illness in an Era of Silence" (Celadon), the Kissingers were a quick-witted, boisterous, suburban Chicago family. "There was a lot of love in that house," a former live-in babysitter for the Kissinger kids says in the book. Yet two of Kissinger's seven siblings died by suicide, and a third has lived with persistent mental illness.

Through interviewing her surviving siblings; digging through diaries and letters, public and medical records; and even tracking down that babysitter from decades ago, Kissinger pieces together the portrait of a clan that's simultaneously loving and troubled.

"I was pulled to the whole idea of what families go through when there's serious mental illness," Kissinger said during a recent interview. "And I don't think that's a story that we tell thoroughly enough."

She hopes her book, which publishes Sept. 5, will encourage people and families to talk openly about their mental health struggles and needs.

With appropriate sensitivity, the news media needs to write about suicide "very robustly," she said, pointing to an essay she wrote on that point for the Columbia Journalism Review in 2018, shortly after the suicides of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain. Journalists need to cover this subject the way they cover other epidemics, she said, pointing out that Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has referred to suicide as an epidemic.

As a trainer with the Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma, Kissinger understands it is challenging to write about suicide, and that responsible journalists strive to avoid triggering contagion effects. She recommends journalists use the resources posted by reportingonsuicide.org, a collaboration of public health organizations and news media organizations.

"The suicide rate is at historic highs right now. It's a public health crisis," she said. In a responsible way, journalists "need to talk about why do people think suicide is a good option, interview people who attempted and survived and hear their stories, talk to families who have been through suicide and find out what that's like."

Parents had problems, but found sobriety

Kissinger, a Milwaukee Journal and Journal Sentinel reporter from 1983 to 2018, grew up in Wilmette, Illinois, the fourth oldest of eight children.

"I've always been nosy, I think by being a middle kid," she said. "I get a lot of satisfaction or gratification out of digging around and telling things."

As she writes in "While You Were Out," Kissinger also once thought of herself as the Marilyn Munster of the family, the normal one among the oddballs, though her book portrays her as just as quirky as her sibs.

Kissinger traces how her parents, Holmer and Jean, brought their own traumas and sorrows to their marriage. "Take two alcoholics — one with bipolar disorder and the other with crippling anxiety — and let them have eight kids in twelve years. What could possibly go wrong?," she writes with a touch of snark that her book suggests runs in the family.

Both of her parents found recovery in Alcoholics Anonymous. She is especially proud of her late father who, after getting sober in 1976, later buried two of his children and his wife without taking a drink.

Their recovery set an example, she said: Surround yourself with enough support, be humble enough to understand and appreciate your limitations and your frailties, and you will have a better life.

"I think the humility portion of that really resonated with me," she said.

A family struggles to cope with two suicides

In 1978, after several prior suicide attempts and hospitalizations, Nancy, the second oldest sibling, ended her life. Kissinger's reaction back then, as described in her book, was complicated:

"Nancy was dead. I'd never see her again. I felt like I should be sobbing, and I was confused about why I wasn't. But for the last several years, I'd been terrified of her. She'd made all our lives miserable. No one wanted to hear that, but it's true. And here's what was also true: She was the most miserable of us all. Each day seemed worse than the last for her."

Holmer, Meg's father, insisted everyone say Nancy's death was an accident. He was concerned that if her death were labeled a suicide, Nancy would have been denied burial in a Catholic cemetery under the rules of the church.

Stigmas around suicide deprive families of the ability to grieve fully, which is a primal need, Kissinger said. "We never sat down as a family and talked about her death," she said.

In 1987, Kissinger published an essay about her sister Nancy's death in the Milwaukee Journal Sunday magazine, infuriating her father, who didn't think she needed to tell anyone about that. But her mother defended her: "That's how she makes sense of it," Jean said.

Then, in 1997, after years of struggle that included jail time for a crime he committed and resistance to taking medication that might have helped, her brother Danny, the second youngest sibling, also died by suicide. (Encouraged by an editor, she overcame her reluctance and wrote about his death the following year for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.)

Kissinger remembered a visit from Danny a few years before that, when he shared that not only did he sometimes think about ending his life, he had taken specific physical actions to see what it would feel like.

"I didn't know what to tell Danny," she writes in her book. "Even then, all those years after Nancy's death, I didn't know that when someone tells you that they have a plan for how to kill themselves, they are in imminent danger." She thought — wrongly, she says today — that encouraging Danny to talk about those fantasies would have made it more likely for him to act.

If she could go back to that moment today, here's what Kissinger would say to her brother:

I'm sorry that you're in such pain. Here's what I can do to help. I can sit with you. You can tell me anything you want to tell me. Together we can move forward and find a way to make you feel better.

Kissinger said in that situation she would not ask "What can I do to help?," because posing that question puts the burden on the person who is suffering.

Catholic church has played a complex role in their lives

As her book details, the Catholic church has played a complex and powerful role in the Kissingers' lives. In contrast to family fears about the church's possible response after Nancy's death, some surviving Kissingers were helped by the church after Danny's suicide. Specifically, the Archdiocese of Chicago's Loving Outreach to Survivors of Suicide (LOSS) program was "a tremendous comfort" to Holmer and Meg's brother Jake, she said.

Not all has been positive: Kissinger recounts how an elderly nun who had taught the children, after Nancy's suicide, whispered to one of the siblings, She's going to hell, you know.

"I love being Catholic," Kissinger said. In spite of the church's flaws, "I can't quit it. It's in my bones."

Her siblings do not all feel the same way, she reports in her book.

She tried to quit the church once, after her mother died of cancer at age 66. "That was too much for God to throw my way," she said. So for one Sunday, she skipped her regular church and attended a different denomination. "I was mad at the Catholic church … I just needed to express my grief." The next week, Kissinger was back at her own parish.

When she complained once about corruption in the church to her father, his response helped her. "This is an institution of men," she remembers him saying. "It's gonna be flawed. But if you focus on the sacraments and what Jesus said, you're not going to go wrong."

After Danny's death, she discovered Holmer was reading the Book of Job for spiritual consolation. In preparation for writing about that in her book, Kissinger read Job and also read a lot about it. "And I still don't understand it," she admitted.

She thought at first that Holmer was interpreting Job, the story of a man whose faith is tested by an onslaught of losses, in a spirit of "suck it up and put up with it." But she came to understand that her father saw Job as "railing against God, having angry conversations," which she approves.

"I think we need to have angry conversations with God," she said. "Speak truth and demand answers. They're not always forthcoming, but you have to try to get them."

Her brother Jake has learned to ask for help

Her brother Jake has lived for many years now with anxiety and depression, working for an understanding employer and engaged with family and other people. So how is he different from Danny and Nancy?

"Jake is a dream patient or a dream person," said Kissinger, who softens when she talks about her brother. "He is humility himself. And this is his saving grace. He is so transparent about his illness."

When Jake feels suicidal, "he will call us and say, you know I'm having these thoughts, and I really don't feel comfortable," Kissinger said. Then the family swarms around him.

She said Jake "has the grace" to ask for help. "I think asking for help is one of the most underappreciated qualities in a human being, and we all need way more of it."

Surprisingly, she resisted getting help for herself

In spite of the two suicides and other family traumas, Kissinger discloses that she had only one appointment ever with a therapist prior to working on her book, leaning instead on her practices of praying, meditating and doing yoga.

"I think I was a little prejudiced against people with mental illness," she admitted. "What greater irony is there that I was spending my days railing against the barriers to mental health care? And I was my own greatest barrier."

On some level, she feared going to a therapist meant she was weak, maybe mentally ill the way her brother and sister were, and that she would die.

When she began working on "While You Were Out," Kissinger started seeing a licensed therapist, because she accepted she would need help processing everything.

Kissinger and her husband, Larry, have two grown children.

"My parenting of them was totally informed by my family experience," she said. Mental health was openly discussed in the family. Kissinger described herself as a hypervigilant parent, always worrying if her children were late coming home.

She's proud that they've become "loving, accepting, compassionate" people with a strong desire to help others. Her daughter works at Tufts University helping students with mental illness navigate life in school.

Truly being 'your brother's keeper'

Kissinger's reporting in the 2000s about the "abysmal" housing options for people with severe mental illness in Milwaukee, including unsafe and illegal group homes, and her later coverage with Steve Schultze of sexual assaults against female patients at the Milwaukee County Mental Health Complex, led to significant changes. These included formation of the Milwaukee County Mental Health Board and creation of supportive housing for people with persistent mental illness.

She is proudest that her mental health reporting led to new housing options. If you needed any anecdotal evidence that mental illness and homelessness are linked, consider this: A woman with mental illness she profiled extensively for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel also ended up as a subject in Matthew Desmond's book "Evicted."

Kissinger does not talk about the mental health system per se, because it's not a system, she said. "A system has to be entities that work together, and nothing about the mental health world works together."

Her dream prescription would include a real system. Not only would your primary care doctor ask you about how you're feeling, but teachers, chiropractors, dentists, even hairdressers also would check in with you. Friends, too, she said. If they pick up on something troubling, then resources would be in place.

"We need to be more comfortable having conversations with people who aren't well, who are showing signs of depression or being withdrawn, and engaging with them," she said.

"It's really looking out for one another," she said. "It's really being your brother's keeper. … It's really loving your brother and sister and looking out for them and caring for them. … That's my dream."

If you go

Meg Kissinger will talk about her memoir "While You Were Out" with Jacki Lyden at 6:30 p.m. Sept. 5 at Milwaukee Public Library Centennial Hall, 733 N. Eighth St. Register for this free event at megkissingermpl.eventbrite.com.

More: Suicides rise in Wisconsin, led by more than 500 gun deaths in 2022

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: In 'While You Were Out,' Meg Kissinger portrays family mental illness