The Stories My Grandfather Didn't Tell

Toward the end, my grandfather told us about the time he was sailing on a United States Navy battleship in the Mediterranean Sea and his convoy was attacked by the German Luftwaffe. In the cacophony and chaos, he watched a gunner on another American battleship in the party turn the great deck guns and shoot a Nazi warplane out of the sky. It spun from the air and crashed into the water not far from my grandfather’s own ship. He told us all this, and then he told us what he thought while he watched it happen.

“That poor bastard.”

This was no surprise to hear from John Shevlin (Jack to those who knew him, Poppy to my family), whose humility and relentless curiosity about the world would never have allowed him to settle for the easy explanation: that the guy in the plane was a Nazi and that was that. It can also be harder to see these things as a clash of civilizations when you and your friends on the ship are only fighting to survive, and you know the man in the plane was just as easily a 20-something kid like you as he was a Nazi of any real description. He was fighting to survive, too. For many of those who truly fight the battles and win, the prize is relief, not glory.

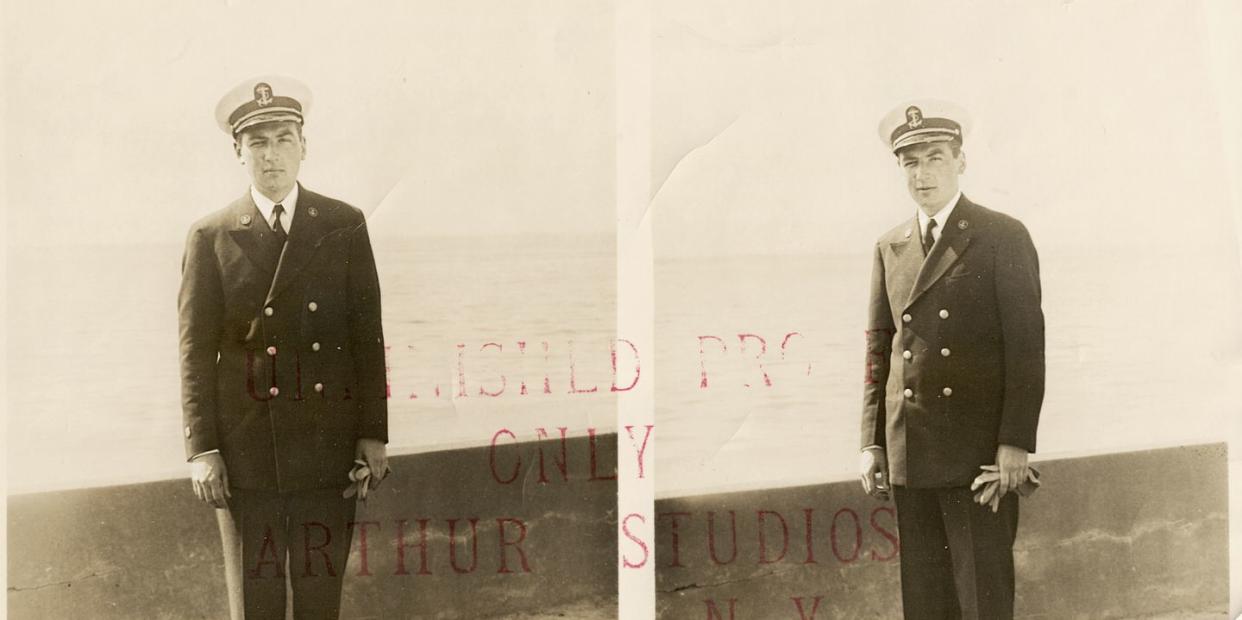

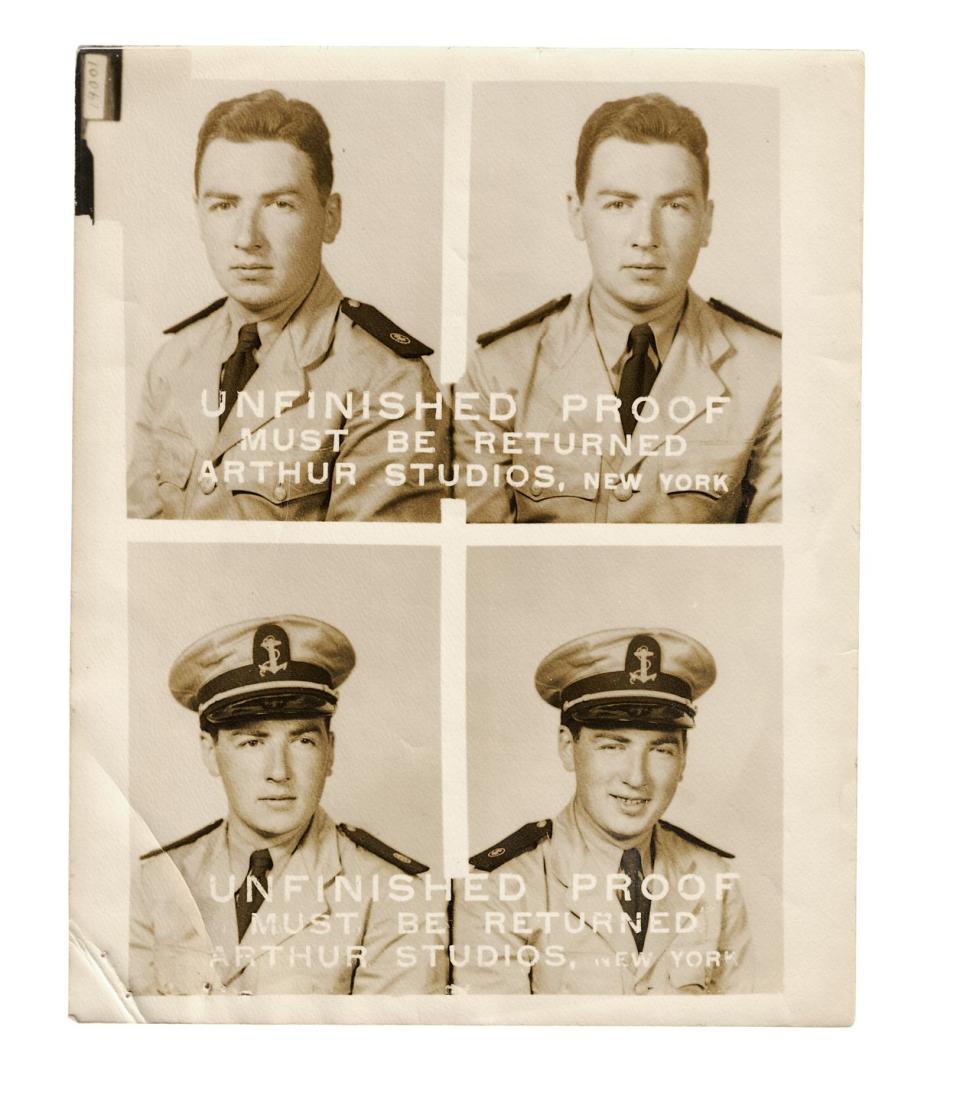

But Jack Shevlin wasn’t just any cog in the war machine. He served as a gunnery officer and first lieutenant on the United States ships Taconic and Frederick Funston. He dodged German U-boats in the North Atlantic and was eventually deployed to the Pacific theater. He was eligible for more than one medal, but we never saw any. By the end of his service, he’d watched the Marines raise the American flag atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima from a boat offshore, but not before he’d seen the kind of horror that would leave any man humble, the kind you don’t talk about until you get to an age when you start to think it’s worth leaving something behind for the record. In fact, my mom didn’t know Poppy had been at Iwo Jima until a few years ago—a few years before he died, at 101 years old, in the summer of 2021. His was a grand life, an adventurous one, a brave and extraordinary and unlikely one for a Depression-era kid born in a pandemic who stuck around long enough to see the next one. He returned from the war, married a pretty girl from down the block in Queens, and climbed the ladder in the textile business. It is a story that still convinces me to believe, as I’ve grown old enough to know the difference, that there is something to be salvaged in this experiment of America.

For years, though, my grandfather was just the waggish charmer who would arrive at Christmas dinner each year in eye-popping plaid trousers. In his proverbial sack, he brought used books from the local store in Cranbury, New Jersey, near his house in later years, or maybe some free weights by the time I reached the age of hammer curls. Alongside all that would be a whole menagerie of aphorisms and pearls of wisdom and winding tales that were just long enough to yank you around a corner and run you smack-dab into a pun. He liked Rodgers and Hammerstein, and he marked news of an achievement—strong grades, a soccer win—with a trademark “Good show!” He had catchphrases for many things, particularly when it came time to leave a function. “Saddle up!” he would say, rounding up whoever was traveling in his car. “See you around campus,” he might offer everyone staying. He was decisive, stubborn at times, a platform of self-belief built over the decades in which he navigated the world with such formidable conviction.

This article appeared in the March 2022 issue of Esquire

subscribe

He learned early on that conviction was what life required. In the depths of the Great Depression, the gasman came to my grandfather’s house in Flushing, Queens, and my great-grandmother answered the door. The man told her that he’d need to come inside and shut off the gas because the family hadn’t paid the bill.

“You’re not coming inside,” she told him.

“If you don’t let me come inside,” he answered, “I’m going to have to dig up the line out there in the street and shut it off that way.”

“Go ahead,” she said.

And soon enough, he was walking away, but not to tear up the street. Nobody had money for that, either, not the city and not the gas company. He just left. And the family still had gas, even if they couldn’t pay for it right then, and even if they had to fight for it by daring someone to take it away. Maybe not all that conviction or that humility was earned overseas.

He certainly made use of it when he returned home from the war. He finished school at Queens College—which cost next to nothing at the time—and got into the carpet business. He joined A & M Karagheusian in Manhattan and took the train in to the Textile Building on Fifth Avenue from a house in suburban Manhasset, Long Island, that he bought himself. When he made money, he invested it well in companies he thought would become more successful—through R&D, through expanding their operations, through offering better goods and services to their customers. Imagine that. It almost sounds a little like that Dream we’re always hearing about.

In a way, it all started with the Boy Scouts. Poppy was an Eagle Scout, and he won a knot-tying contest at a jamboree. He was spotted by a scoutmaster from a neighboring troop who asked him to switch. He did, and that’s where he met his best friend, Bob Keyes, who had a little sister named Leonore who would one day become my grandmother. But it was also that same scoutmaster whom he’d turn to for advice after Pearl Harbor, when it was clear the second great war of the century had arrived and would soon catch all the young men up in it. “You know, they’re starting an officer training course at Kings Point—the Merchant Marine Academy,” he told Poppy. “I think you should do that.” So he did. Eventually, when my grandfather joined the Navy, his commission as an officer was the difference between storming beaches off a Higgins boat and telling the boat where to land from the main ship. It might just have saved his life, something he came to appreciate when, in one of many battles in the Pacific, the crew on board got a report that an officer running things onshore had been killed. Poppy’s commanding officer told him he’d go to the beach to replace him.

He thought one thing: Who, me?

Growing up, my Mom didn’t hear most of the stories. My grandfather didn’t tell them. She heard the fun ones, like when a member of his crew got sick off the coast of North Africa and Poppy signaled by semaphore to the shore that they needed a doctor. After a while, a boat pulled up to theirs carrying, to the amazement of the Americans, a local shaman. Poppy used his shore leave to visit the pyramids of Giza on camelback and to go on safari. He wanted to know things, and see things, and find out more about them and how they worked. In his downtime in the Navy, he took tests until he was certified to serve as chief mate on any ship in any ocean.

My mom has said she thought it was his curiosity that saved him when he lost his wife, whom we called Moppy, to lung cancer in 1997. He himself was lost, perhaps for the first time, until he started attending classes at Princeton University. He relished the knowledge on offer there, the expertise of the professors who taught classes for seniors. He soldiered on for decades, sending all of us articles and books to read at every opportunity. And the next time you saw him, there would always be a test to see if you did the reading. Two weeks before he left us, I was given a pop quiz on an article he’d sent me about China’s rise as a global superpower.

He loved to make games out of the world, maybe because he knew that so much of it wasn’t a game at all. He could find a game in the stock market or the supermarket, where he’d make the rounds to secure as many free samples as possible. It was fun, sure, but I now understand there was something of his childhood left in his quest to never waste a penny. He would have told you that his funeral this past summer was too much of a production. He kept cars for 20 years—Japanese ones, because they’re reliable. There was scarcely any resentment toward the old enemies or the new—none of Mad Men’s Roger Sterling in him, no matter what he saw in the Pacific. He kept up with the times admirably, growing to accept the country’s great faults and how he’d had chances that others hadn’t without losing his faith in the whole enterprise. And that’s a faith worth salvaging, from one generation to the next.

He was a devout believer in the power of luck, acutely aware that he and all the rest of us are governed by, but not subjugated to, the way fortune ebbs and flows, ordinary lives made extraordinary through some combination of happenstance and our own force of will. It was a remarkable ride, unremarked upon for so much of his life because he wanted it that way. The kind of story, then, that you might find in a magazine.

You Might Also Like