How to Store Cherries

My piled-up, rotted room temperature cherries walked so your laid-out fridge cherries could run.

Serious Eats / Amanda Suarez

TL;DR:

Cherries require coolness and dryness. Getting your cherries in the fridge—and quickly—will automatically keep them fresh longer. If you skip washing and lay them out flat (rather than pile them on top of each other in a bag or container), you’ll see even better results. I found I could make cherries last a full eight days at peak ripeness with that particular treatment.

One can, when strolling under a laden cherry tree, pick a couple of the dangly fruit and—assuming one has pierced ears—insert the stems through the piercings to create beautiful jewelry that also happens to be a handy method of storing the cherries for snacking later. One can. But that only nets you two cherries. As proud as I am of this innovative cherry-storage idea that you definitely will never see anywhere else, there's got to be a better way. My job was to find it.

After testing all the major cherry-storage variables with pounds of sweet cherries and deeply probing the agricultural-science literature on the topic, I now have an answer that not only works for more than two cherries, but almost definitely ensures they'll last longer than the earrings idea I'd started with. Science is progress, folks, it really is.

Storing Cherries: What's Our Goal and What to Test?

Cherries are the bright red fruits, always in a pair of two connected by beige pixelated stems, that Pac-Man gets to eat for a bonus of 100 points. Oh, sorry, wrong article. Let's reset: Cherries are an actual, living fruit in the Prunus family, cousin to peaches, nectarines, plums, and apricots. Technically, they are a drupe, which is a word that makes them sound way less cool than they are. Better, then, to use the colloquial synonym: stone fruit.

While small by stone-fruit standards, cherries at their best are plump and juicy, with shiny skins and no visible bruising, splits, or rot. There are two main types of cherry, sweet and sour, and while my testing focused on sweet cherries, which are more commonly shipped when not in season locally and thus easier to find, I'm fairly confident that the tips here will be relevant to both varieties.

One thing that differentiates cherries from many of its other stone-fruit cousins is that it is considered a non-climacteric fruit, meaning it does not continue to ripen after being picked—the cherry you buy at the store or market is as good as it's going to get. This fact makes my cherry-storage job easier, since there's no need to try to optimize storage for ripening the way one does with something like a peach. Instead, the name of the game here is maximizing the cherry's existing quality over time. Put another way, we just need to find the best way to make them last.

How does one do that? Well, as mentioned above, you do two things. First is research, primarily reading up on the work food and agriculture scientists have already done on the topic, to better understand the major concerns and challenges identified by very smart people with a large financial interest in getting this whole shebang right. The second is to buy lots and lots of cherries and actually put all that wisdom to the test in a home setting, along with any other questions that may not be answered in the existing literature—after all, the cherry industry is most concerned with what happens from farm to point-of-purchase. Cherry-storage best-practices at home are not really their problem.

After doing my own reading and also applying a healthy dose of common sense, I narrowed down the variables I wanted to test to the following: pre-washing the fruit vs. not; cold vs. room-temperature storage; air-flow and container options; and stemming vs. not. Here are my results.

To Chill or Not to Chill?

It turns out cherries, summer darlings though they are, hate the heat. In fact, I couldn’t find a single source, reputable or otherwise, that told me cherries shouldn’t be cooled, and quickly. And not only is cold important, but how quickly and consistently you get and keep them cold. One cherry- storage study conducted for The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology over the course of three years (!) determined that cooling cherries within 36 hours of harvest (and maintaining their coldness) directly correlated to the longest-lasting quality cherries.

Serious Eats / Tess Koman

As for the optimal temperature for cherry storage, opinions range, but not by much. The JHSB study IDs 0°C (32°F) as the best temperature for preservation; others point to a range of -.5°C–1°C (33–34°F) as the sweet spot. So I stuck a bunch of washed and unwashed cherries in my admittedly slightly warmer 1°–4°C (34°–39°F) fridge. I putzed around for about 35 hours and then stuck in a bunch more. I waited until that 40-hour mark hit and threw even more cherries in. And, just for funsies, I left a bunch of cherries in various states of cleanliness on my allegedly far-too-hot (read: room-temp) counter and kept them there forever.

As you may imagine, my warm kitchen-table fruit was the first to go. Just hours into the experiment, the beginnings of brown cherry sludge appeared at the bottom of each storage vessel. The next day, there were fully bruised cherries in each batch. Day three and we were down for the count, baby. Like, fully squished and gross and inedible. Day! Three!

To Wash or Not To Wash?

We know from food-storage-testing experience that some types of produce benefit from a wash (hello strawberries!) before being stored while others don't (lookin' at you, peaches). Water, it turns out, can be one of a cherry’s least favorite elements. This study from Oregon State University demonstrated that excess water sitting on a cherry’s surface can penetrate its cuticle and cause those hardened cracks you likely don’t enjoy eating. But that's a study of cherries dealing with water exposure in the field, and we're looking at whether we should wash cherries at home—plus, at home we can dry them after washing.

To that end, I experimented with washing cherries in both hot (49°C; 120°F) and room-temp (25°C; 77°F) water, then drying them completely in a paper towel–lined salad spinner before taking any next steps. I also left several batches unwashed as a control. All the cherries were then stored in 1) their original bagging, 2) a large, flat bowl, or 3) an airtight container.

Serious Eats / Tess Koman

I only ever saw mold on cherries that had been washed. By day five, my cold water–washed cherries began to mold. By day six, my hot-water cherries began to mold as well. I did not see any mold on the unwashed cherries in that same time frame—in fact, I didn’t see mold on them at all.

Serious Eats / Tess Koman

I don’t know why exactly rinsing the cherries with water induced rot the way it did, even when I did my best to dry them well after. It’s hard to believe a cherry is more at risk when exposed to water than a thinner-skinned strawberry is, but that seems to be the case. Is it possible that the level of drying required would have included individually blotting any hidden drops of water from each and every cherry? I…don’t regret not doing that, because who has the time or energy (more on that in a bit)?

The takeaway here seems clear: skip washing until you're ready to eat your cherries.

To Crowd or Not to Crowd?

Another largely agreed-upon belief in the world of cherries is that storing them piled on top of each other causes bruising. Bruised cherries can still be edible, but that flesh quickly decays into something much less appetizing. Plenty of things can cause bruising: transport damage, temperature, or packing.

My cherries were big, averaging 7.5 grams a pop. To test whether piling cherries on top of each other (or even just leaving them in the deep bags they're sometimes sold in) would harm them in the long run, I kept each batch in both heaped in the original packaging and laid out in a single layer in a bowl.

Overall, all my laid-flat cherries fared better than the ones that were stored vertically. Not a single one of my flat cherries bruised—tens of my piled ones did, particularly ones at the bottom of the piles, beginning at day four. I still would’ve eaten them until day six 1) when just enough sticky cherry juice had accumulated at the bottom of each piled vessel to make me cringe and 2) the cherries were so soft they were oftentimes hard to actually grasp without slipping out of their skins and my fingers.

Again, I had no issues with slipperiness or large quantities of leakage with my flat cherries. That said, it’s not always possible to clear fridge space for anything, let alone a large receptacle holding a single layer of cherries. But if you can slide a plate onto a fridge shelf and line the whole thing with a single layer of cherries, you’re going to be able to keep those cherries for longer than if you stash them in the fridge in their original packaging.

To Stem or Not to Stem?

I was also interested in experimenting with moisture loss as it pertained to cherry stems. We've seen before with tomatoes that the stem end of the fruit can be a weak point in its longevity, since moisture can exit through the scar left behind by the stem faster than other parts of an otherwise healthy fruit. In the case of tomatoes, simply storing them stem side down is enough to keep moisture from exiting the fruit too quickly. Of course tomatoes don't usually come with the vine still attached, whereas cherries often do still have their stems, though not always.

Serious Eats / Tess Koman

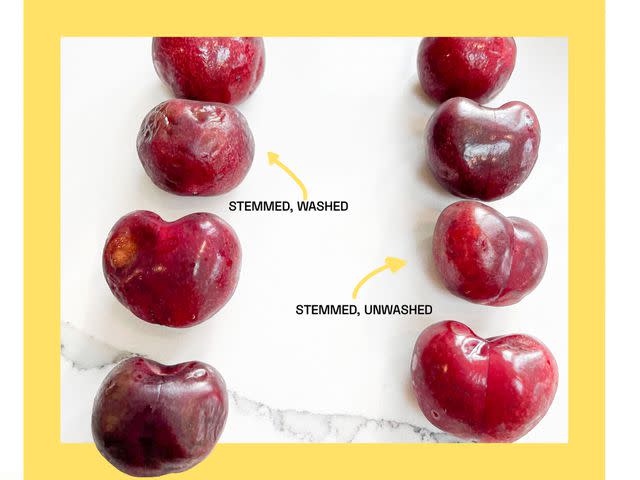

While the stem status of a bunch of cherries is not something that's easy to control as a shopper, nor would I suggest anyone go to the trouble of lining up all their individual stemless cherries stem side down, I still wanted to know—does the presence or absence of the stem matter? To find out, I stemmed a portion of my cherries and weighed them over the course of several days, comparing the results to a control batch that still had their stems. Within a three-to-five–day period, I watched as the stemmed cherries withered and softened while the stem-on ones remained robust, a clear indicator that cherries without their stems are much less likely to be long-lived.

What's the practical application of this? Well, for one thing: Keep! Stems! On! Cherries! At! All! Costs!! But is anyone really nuts enough to stand around pre-stemming cherries before putting them in the fridge? I suspect (hope?) not. So, more realistically, what this means is that when shopping, try your best to get cherries that still have their stems attached if at all possible.

How to Store Cherries So They’ll Last Longest, Step by Step

The long and short of it is that cherries can be kept glorious for about eight or nine days if you get them in the fridge quickly after shopping. From there, you can certainly leave them in their original packaging for a good week, but the extra effort of laying them out flat should eke you out an extra two days or so. Regardless, you should not attempt to clean your cherries before you get them in the fridge. Cold and dry is the name of the game here.

Try to buy stem-on cherries.

Keep your berries out of the heat as much as possible on the way home.

Remove any decaying or cracked cherries from the bunch.

Put them in a bowl large enough to lay them a single layer as best you can. Leave the bowl uncovered.

Place the bowl in the fridge and close that fridge door ASAP.