Steven Canals Spent Years Hiding. Now Everyone Can See Him

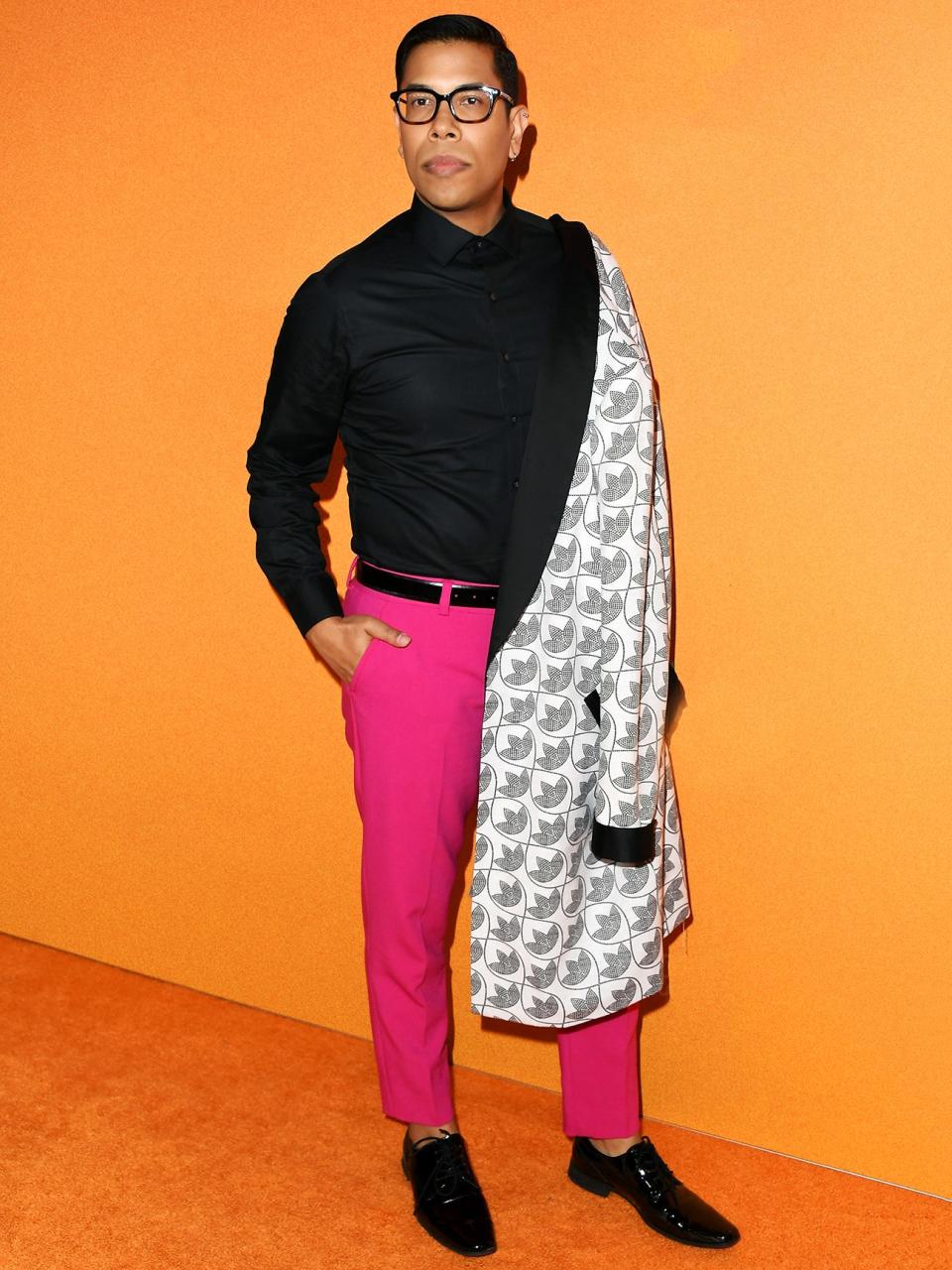

Steven Canals is quietly sitting here. He’s wearing what he's wearing, and no one knows that it's this man who created the most glamorous, most ostentatious, most eleganza-packed show on TV right now. He is, after all, the co-creator and executive producer of FX’s breakout success Pose, the LGBTQ ballroom melodrama that has become a hit for not only its style but its heart. On a Wednesday morning, Canals blends in with the other New Yorkers grabbing breakfast at the Upper East Side café Irving Farm, sporting black-rimmed glasses, a neon blue sweatshirt with a pin that says “Shh. Stop Talking,” and a knapsack. The only difference is that he is, in fact, preparing for the ball, even if he doesn’t look like it.

You would also never know from Canals’s demeanor that it’s just less than a week until Pose’s Season Two premiere. There are no worry lines, no exasperation. His bites of overnight oats are as measured as his speech. Today he’s happy to be home. “Now, with the city being cleaned up and gentrification, the city has a different personality and vibe. I miss it,” Canals, 38, says.

Although you’ve probably associated Pose with Canals’s co-creator and powerhouse Hollywood producer, Ryan Murphy, and his partner, Brad Falchuk, the duo behind American Horror Story, Glee, and Scream Queens. But Pose really begins with Canals.

The kernel of the idea for Pose first formed for Steven Canals in college. After a professor screened Jennie Livingston’s ballroom documentary, Paris Is Burning, for Canals’s class his junior year, he contemplated how the canonical film would make an enticing TV show. The way he envisioned it: an homage to his beloved film Flashdance in which a young black boy who wants to be a dancer moves to New York and gets enmeshed in a war between two house mothers. “I was like, ‘I can’t wait to see that,’ ” he says of the story. “I just never thought I would be the person to tell it.”

While Canals has lived in Los Angeles for the past seven years, his roots stretch back to the Bronx. Growing up as a black, brown, and queer youth in the 1980s, Canals experienced a bleak, gritty city, living in housing projects during the HIV and crack epidemics. “It was a really scary time, and I was a really sensitive boy,” he recalls. But Canals found solace in spending a lot of time at home watching film classics. His father’s passion for movies ignited his own as Canals was introduced to the works of directors like Stanley Kubrick and Francis Ford Coppola. “My mom, in particular, was very overprotective and scared that the city might swallow me whole,” he says. But staying inside and watching movies? It kept Canals occupied.

At 15, as New York emerged from the crack epidemic in the mid-’90s only to be swallowed by a new wave of gang violence, Canals found solace in movies. He joined an after-school program, called Youth Ministries for Peace & Justice, that allowed him to focus on creating stories of his own for the first time. For nearly eight months, Canals and nine of his classmates worked on producing a documentary short about turf violence. Then, a week before they were finished editing the documentary, one of his classmates, a co-producer on the project, was shot and killed. “Her death is probably the greatest catalyst for me to say ‘I want to become a filmmaker,’ because I went from being someone who was highlighting an experience to suddenly having the experience,” he says. Canals recalls something his mom used to say: “From death emerges new life.” He didn’t want his classmate’s death to be in vain. “That was the moment I knew I needed to devote my life in some way to telling a story,” he says.

Canals doesn’t look back on high school fondly. “My K-12 experience can be summarized in the following way: being teased relentlessly and going from being called a ‘girl’ to a ‘sissy’ to ‘gay’ to ‘faggot,’ ” he says. “I tried really hard to just not be seen.” He remembers once quietly raising his hand during attendance and everyone turning to look at him. “My teacher was like, ‘Why is everyone reacting like that? Does he have a big mouth? Is he a troublemaker?’ And I remember one of my friends in the front saying, ‘No, I just didn’t think anyone realized he was here,’ ” he says. “And I think that was really indicative of what I tried to make high school for myself—I tried to disappear.”

After graduating at 17, Canals took two years off before applying to college. “I got rejected by every institution I applied to,” he says, in-between claps punctuating his every word. He eventually landed at Binghamton University for undergrad and grad school, where he enrolled in the school’s cinema program. There he came out as queer to a handful of people, though he still struggled with deeply internalized homophobia. He also found that he was still searching for purpose and his own voice, still trying not to disappear.

An online quiz, of all things, changed his trajectory. Once he graduated from Binghamton in 2005, he worked as an administrator at SUNY Cortland for six years while attending classes for his master’s degree part-time. At 30, “I stepped into my queer identity, but lost a creative sense of self,” he says. Then he took that quiz, which concluded that he should be a screenwriter. So he applied to UCLA's MFA screenwriting program, getting in despite the school having “an [acceptance rate] as low as Harvard’s.” This is where that kernel starts to grow.

While at UCLA, he created Pose to fill in a gap. That gap? “Not seeing a lot of black and brown people who happened to be LGBT on television,” he says. In 2014 he wrote the first script for Pose. As it circulated, the most positive feedback he got was that it should be a movie. “It was too much. Too many black people. It was too queer. It was a period piece,” he remembers.

“I had met with 150 executives: There was no single person who said they wanted to buy it or develop it,” says Canals. And then he showed the script to Sherry Marsh, an executive producer of the History Channel show Vikings, who told him she wanted to pitch Pose as he intended it. Which meant helping Canals get the script in front of Ryan Murphy, just two weeks after Murphy won the Emmy for The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story. After 45 minutes, Murphy agreed to make Pose with him. As a longtime fan of the small-screen legend’s work, Canals couldn’t believe it. “Every time the phone would ring, I was convinced it would be the call where he’d change his mind,” he says.

The first season of Pose, which premiered last June, centers on the black and Latinx ballroom subculture in the LGBTQ community during the rise of white yuppie culture and HIV/AIDS crisis in 1987–1988. During that season, Blanca Evangelista (Mj Rodriguez) leaves the House of Abundance, under house mother Elektra (Dominique Jackson), to form her own house, where she takes in aspiring dancer Damon Evangelista (Ryan Jamaal Swain), trans woman sex worker Angel Evangelista (Indya Moore), and street-savvy hustler “Lil Papi” Evangelista (Angel Bismark Curiel). They’re all guided by Pray Tell (Billy Porter), a mentor and designer for the ballroom community. Straying from Paris Is Burning ultimately became the key to making Pose. Canals and his writing team didn’t want to be restricted to telling the stories of real people.

The bones of Pose, however, are taken from Canals’s real life. “Damon is absolutely teenage, early-20s Steven through and through…minus the parents kicking him out of the house,” says Canals. Blanca is inspired by his mom, while Lil Papi is a tribute to the boys who befriended him in the Bronx that were straight and couldn’t care less that he was gay. “They were just gonna be kind anyway,” he says with a smile.

The through line of representation seen in Pose’s stories blooms from the show’s diverse writers room, a Hollywood anomaly: two trans women, Janet Mock and Our Lady J, as well as Canals, Ryan Murphy, and Brad Falchuk. For Canals, having Mock, a black trans woman from Hawaii, and J, a white trans woman from Pennsylvania, in the room has been integral to crafting Pose’s diverse storytelling. “Working with two unique and powerful trans women is just a reminder that we are not a monolith,” he says. But he knows that the reality of television is that there’s usually room for one LGBTQ person, one person of color, or one woman at the table. “More often than not, you see the writers rooms that are being constructed by primarily cis men who aren’t white and are being populated by cis men. Then there’s only space for one woman, one LGBTQ person, or one person of color. And it’s like no: Just create a table and have seats for us. We should just be a natural part of the hiring process, we shouldn’t be an afterthought,” he says. Canals and the team believe in representation and refuse to co-op other people’s narratives, so Pose compensates a number of consultants from the ballroom community to aid in telling the show’s story.

Porter praises Canals for creating a show that has not only created so much visibility but helped him find his own path. “Steven is a visionary,” he says. “He’s so talented, and he’s uncompromising in terms of his intentions and his mission to tell these stories of LGBTQ people of color. It’s been so comforting, inspiring, [and] it feels like I landed in the right place after a long time of not feeling like I had a place. His vision has helped make a place for me. He just takes my breath away.”

Like Porter, Canals knows what it’s like to not feel represented. Last year he was notably left off the Out100 list, which featured co-creator and executive producer Murphy, writer-director Mock, director Silas Howard, and actors Porter, Moore, Jackson, and Rodriguez. But it wasn’t about not seeing his name in there: It was about not seeing Afro-Latinx people on the list. “In an industry where it feels like the Afro and Afro-Latinx voice isn’t valued, that was the part of it that stung for me. It wasn’t about me specifically,” he says.

1067873968

Jon Kopaloff/Getty ImagesSeason Two of Pose, which premiered on June 11, features a time jump. It’s 1990 in New York: David Dinkins has become the first black mayor of New York City, ACT UP’s presence in fighting for the rights of HIV-positive individuals is stronger than ever, and the release of Madonna’s iconic hit “Vogue” empowers the queer community. Canals says the show will continue to focus on HIV/AIDS activism through Pray Tell, while Angel will pursue a modeling career. Blanca will learn how to encourage all of the members of her house to live their best lives. “For all the characters [in Season Two], it’s about: What do they want? What do they really want?” says Canals.

Canals, on the other hand, knows what he wants, now that Pose has made an impact. He has a purpose, he says. “Pose isn’t about elevating Steven Canals—it’s about elevating queer and trans people of color,” he says. “I’m hoping that on the heels of my success we’ll see more doors open so that more people of color, more LGBT people, and more women will have more opportunities.”

As Canals looks toward creating visibility for under-represented communities, I ask him about his own visibility. Does he, the teenage boy who only wanted to “disappear,” finally feel seen now that Pose has become so beloved? And if so, is he okay with it? “I am,” he says, then pauses. “I’m now comfortable with my own voice, using it and also the sound of it, and I look at Pose as a really wonderful example of how to use your voice for good.”

Originally Appeared on GQ