Stephen Sondheim could break your heart and make you hear the world anew

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

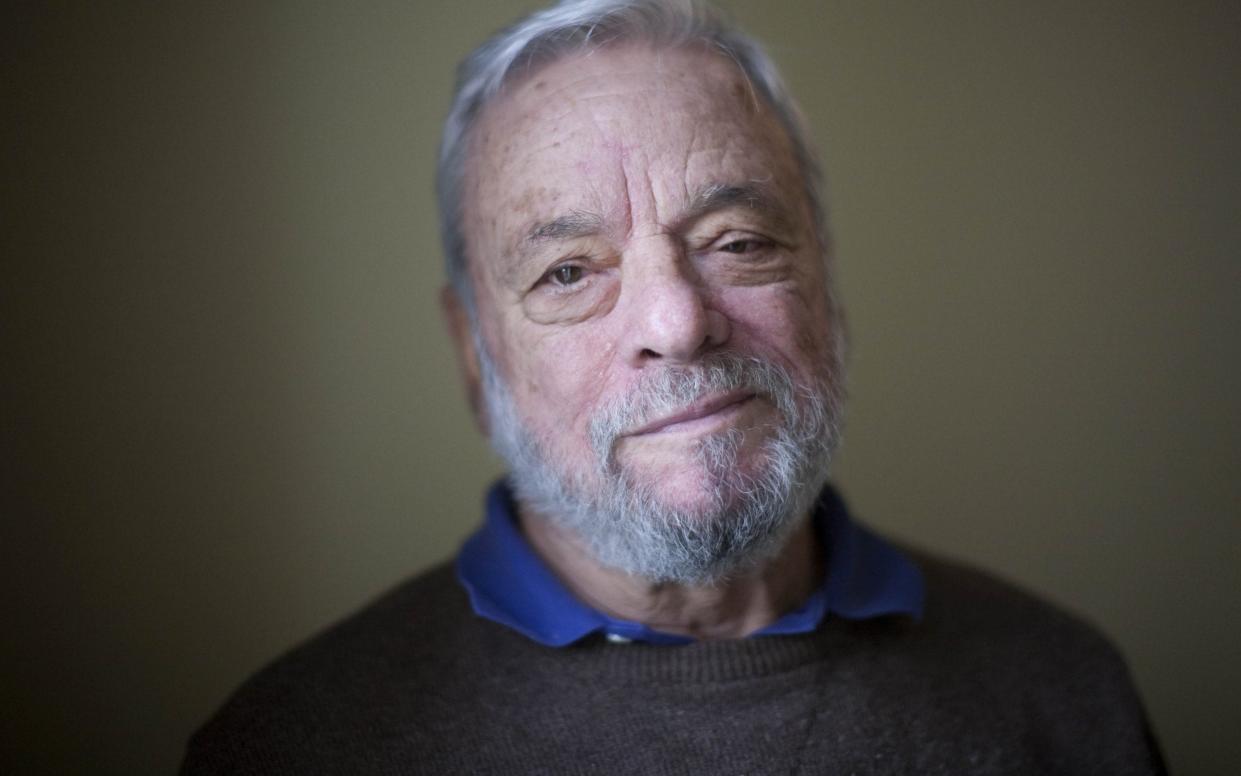

Stephen Sondheim, who has died aged 91, was the towering genius of mid-late 20th century American musical theatre, whose reputation at home and abroad continued to grow in the new century. As a peerlessly talented composer, lyricist and theatrical visionary he revitalised the form, renewing and enhancing its status. His work will live on, his influence will endure. Whether anyone will come close to matching his achievements is debatable.

Andrew Lloyd-Webber far out-stripped Sondheim for ticket-sales on Broadway. But there’s no question which composer mattered more to American theatre or bestowed more prestige and legitimacy on the Great White Way as a crucible for new musicals.

Sondheim’s variable commercial fortunes in his native Manhattan flowed from his appetite for complexity and challenging material. He had his share of ‘flops’, most notoriously Merrily We Roll Along, which ran for 16 performances after opening in 1981, and almost saw him quit theatre for good. It has since been hailed as a classic.

His work blossomed at times in the West End but benefited most from London’s off-West End and subsidised stages. Many of his shows were given a new lease of life in the UK over the past few decades, some of them transferring to New York (most recently Marianne Elliott’s gender-flipped Company). An Anglophile, he penned Sweeney Todd, perhaps the most remorselessly thrilling (and the most gruesomely entertaining) British-set musical ever written, as a love-letter to London. The special relationship was confirmed with the renaming of the Queen’s theatre after him in 2019.

Above and beyond embodying a spirit of Anglo-American mutual admiration, Sondheim represented a crucial bridge between the so-called "golden age of the American musical" (c1925-1960, he suggested) and an era when Broadway’s cultural pre-eminence waned in the face of the proliferation of rock and pop, and growth of television.

His oeuvre is indebted to what came before - sometimes, as in the case of Follies, which evoked, via pastiche, the glamorous vaudeville aura of Broadway in the interwar years, adoringly so. But he was a pivotal figure, looking forward and understanding that musical theatre could thrive if it dared to be as ambitious and unformulaic as possible.

He had the good fortune to be mentored by the lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II (with composer Richard Rodgers, the most successful musicals writer of his era), who became a surrogate father figure when his mother and he moved to live nearby in Bucks County, Pennsylvania following his parents’ divorce. A decade on he was in the right place at the right time again, instrumental in the birth of a more abrasive musical sound: collaborating as lyricist with Leonard Bernstein on West Side Story (1957) and Jule Stein on Gypsy (1959), both of which advanced the form, and entered the canon.

What, broadly put, was his distinctive contribution? Though he could muster music that was romantically lush, he was never uncomplicatedly genteel or sentimental. He had an attitude to life that one might describe as ‘the less deceived’. Where Rodgers and Hammerstein gave the world “Some Enchanted Evening” (in South Pacific), Sondheim gave us evenings of much disenchantment. Where their landscapes were often – think Oklahoma! and The Sound of Music – expansive, even escapist, Sondheim’s were claustrophobic, often metropolitan, angst-ridden.

If America in the 1950s was a time of optimism, he soaked up the contradictions and difficulties of what ensued in the 1960s – freedom and affluence, also instability and confusion.

His work is rife with dark, jangling emotions - cynicism, acrimony, regret, disillusion, loneliness. He did little to soothe the brow of the Broadway-goer yet he offset those "negatives" with humour and a musicality as rich and unpredictable as humanity. He wanted to entertain people, yet to do so without offering false comfort, easy times.

After the sophisticated (albeit rather effortful) comic crowd-pleaser A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), a spoofy Roman farce, established him with the public, he fully found his voice with Company (1970), detailing the mid-thirties life-crisis of an unattached New York bachelor, urged to settle down by his friends. He said of it that he wanted “a show where the audience would sit for two hours screaming their heads off with laughter and then go home and not be able to sleep”.

That show essentially deconstructed the usual model; where musical songs had been integrated to assist the dramatic thrust he now pulled at the structure, dispensing with a strong plot, allowing the songs to sit in a tangential relation to the action.

There were old-fashioned antecedents in terms of musical revue, and he was also following in the experimental footsteps of Rodgers and Hammerstein. But with Harold Prince directing, the show had the shock of the new. Here was something acidly funny, dripping with melancholy and fresh (hailed by some as a proto "concept musical") which declared itself not as a lesser branch of theatrical entertainment but as worth serious consideration as a work of art.

It revealed a creative mind that took relish in unravelling psychological states – and in pushing the form, the audience, his singers/actors/musicians almost to breaking point. Take one single sustained howl in Company – the word “aaaaah”, held for ages by woozy, embittered Joanne in the waspish, socially sardonic number The Ladies Who Lunch. For all his lexical ingenuity, there you have quintessential Sondheim: not easy on the ear, a ripping of convention.

To quote the title of his arch mash-up of fairy-tales, colliding familiar folkloric characters with eachother and a postmodern sensibility, he took audiences Into the Woods. If there was reassurance in facing inner demons, it was hard-won. You can see why he inspired cult-like devotion.

In the theatre, he offered a secular repository for extreme emotion, and through his art, the transcendence of it. In his master-work, Sunday in the Park with George – itself about the making of a masterpiece, Georges Seurat's pointillist painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte – he encapsulated the agony and ecstasy bound up with self-expression. At one level a self-portrait; at another a picture of us all. Above the serrated wit, there’s a rare wisdom in Sondheim about the human condition.

Owning much to his collaborators (book-writers like George Furth, John Weidman and James Lapine, director Prince also hugely important in his 1970s heyday), he refuted the idea of a grand thematic project, and of clear biographical connections with his output. Given his troubled, if affluent early life, and toxic relationship with his mother, they’re not hard to find and, overall, it’s possible to detect distinct patterns of preoccupation.

In the fretfulness of Company, the melancholy ache of Follies, the forward trajectory of Pacific Overtures (which showed Japan succumbing to American economic might, and embracing runaway capitalism), the backward trajectory of Merrily We Roll Along (which followed a jaded friendship back to its youthful source), and in the grotesquery of Assassins – which assembled a rogue’s gallery of US presidential killers - he explored the soul of modern man and the rough terrain of the Americanised psyche, the gap between what you’re led to expect awaits you, and the bruising reality.

His productive period ended more with a whimper than a bang – ironically back with an idea he had had early in his career: Road Show (much reworked) looked at the early 20th century American pioneers brothers Addison (architect) and Wilson (conman) Mizner. It lacked his usual flair but too much had been accomplished for that to matter much. The latter set gay characters centre-stage in his work for the first time – and looking at his oeuvre, you sense that it’s a product of its age in terms of the dominant heterosexuality of the characterisation. But if that’s a failing, it hardly dooms the work.

Elsewhere Sondheim could perhaps be too cerebral for his own good. Passion, say, expressed a consummate craftsmanship, but sometimes the exactness of his lyrics had a deadness; he could artfully describe passion more than he could convey it.

Yet even at his most sleekly "accomplished" – as in A Little Night Music, derived from the Bergman film Smiles of a Summer Night – he could break your heart and make you feel you were seeing/ hearing the world anew. Its indestructible gem is Send in the Clowns - his best-known number (recorded by over 900 artists, Sinatra included).

The song perfectly encapsulates his capacity for expressing ambiguity and paradox, at once succinct and yet hard to pin down, a romantic ballad of almost connection, two people so near, so far: “Me here at last on the ground/ You in mid-air...One who keeps tearing around… One who can't move.”

The reaction to a kind of tragedy? To regard it, wistfully, helplessly, as a kind of comedy: “Send in the Clowns…” Shakespeare, to whom Sondheim was sometimes compared, was a master at that kind of mingling of contrary moods. And it’s to Shakespeare we should turn in final tribute, taking a leaf from Hamlet: “[We] shall not look upon his like again”.