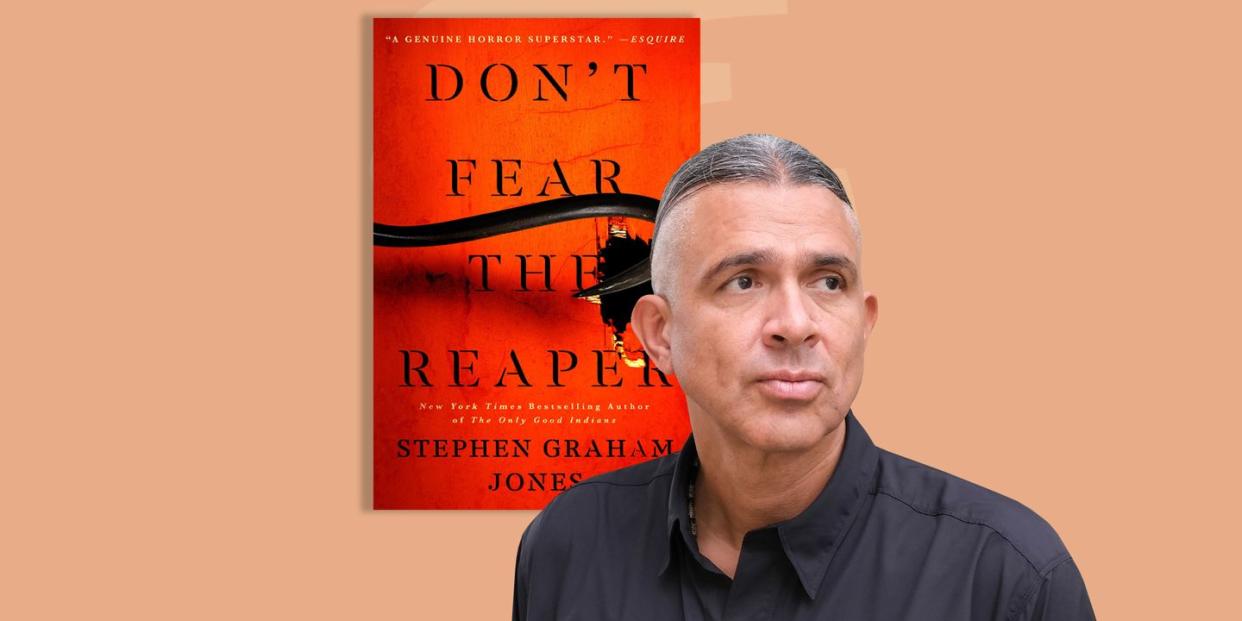

How Stephen Graham Jones Is Reinventing the Slasher

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Hemingway once wrote that bankruptcy occurs gradually, then suddenly. For Stephen Graham Jones, success arrived in much the same way.

Jones is horror’s voice of the moment. His books excite new readers, while indie fiction veterans look on with a told-you-so nod. In a genre enjoying an unprecedented variety of voice and topic and tone, Jones is part of the new vanguard. His stories put his Blackfeet tribal ancestry, his exhaustive pop culture knowledge, and his academic credentials to use in shaking up how horror fiction operates. Readers can’t get enough.

It wasn’t always this way, though. For two decades, Jones has been publishing weird, experimental fiction that disregards the demands of the market. It was only after he had well over twenty books in print that the wider world began paying attention. His breakout came in 2020 with The Only Good Indians. What sounds like a simple morality tale in summary (five Blackfeet men face a supernatural reckoning for unscrupulous hunting) in fact becomes an ambitious treatment of guilt, family, and cultural connection. Jones tends to downplay such grandiosity, instead describing how the story began with his desire to “take Jason up to the reservation, to see how he’d fare.”

He is referring to Jason Voorhees, the hulking killer from the Friday the Thirteenth franchise. Jones wanted to write about him because he loves slasher movies. Seriously loves them. He’s a walking encyclopedia of the sub-genre. With existing IPs out of bounds, Jones created his own avenging monster: the Elk-Headed Woman. She is destined for iconic status the moment the film adaptation is greenlit.

If The Only Good Indians had the rough shape of the slasher, Jones’ next novel left its inspirations in no doubt. 2021’s My Heart is a Chainsaw introduced readers to Jade Daniels, a high school girl with a raft of personal problems and a fixation on the slasher. When a killer arises from the chaotic gentrification of her hometown, Jade must bring all of her movie experience to bear. She does, with countless obscure references and deep-dive monologues. For Jones, she’s “a funnel, someone that I can pour all this trivia, knowledge, and tricks into.” Chainsaw is no empty intellectual exercise in self-reflection, though. Behind the easter eggs, it’s a story about trauma, survival, and what it takes to be a hero. It was a huge success, and like all good slashers, it demanded a sequel.

Now, in Don’t Fear the Reaper—the second installment in what is now being called the Indian Lake Trilogy—Jones takes us back to Proofrock, Idaho for another showdown. As he explains, “It’s four years later. Jade has grown up, and she doesn’t wear her slasher love on her sleeve and her hair and her eyes anymore.” What will happen then, when a new killer comes to town? Jones joins me via Zoom, from a freezing cold Montana night, to dig into what the slasher means to him.

ESQUIRE: The question we have to begin with, Stephen, is why slashers? What about that sub-genre so appeals to you?

Stephen Graham Jones: I fell in love with slashers when I was in eighth grade. I was living down in Austin, Texas and I got to running with a group of friends. Every Friday after school we’d go to the video rental place. Someone’s brother worked there and we could sneak out with a stack of seven or eight slashers. If we had them back early enough on Saturday, they didn’t have to log them as gone, so we never had to pay. Every Friday night, we’d go to a friend’s house way out in the trees. He had a separate garage and his dad put an old TV and VCR in there and a ratty couch and we’d watch Freddy and Jason and Michael do their thing.

$23.99

amazon.com

Were you scared?

We’d just yell and cringe and have fun. And then, around two in the morning, that friend’s dad would get deep enough into his case of beer that he’d put on an old Freddy Krueger glove and come scrape the plastic claws on the outside of that garage door. We’d scream and pile outside and just run through the darkness. For some reason, if we made it to the trees, we thought we were safe. But that feeling, of running and screaming and grinning with tears running back along your face—to me, that’s the essential characteristic of the slasher, and I think that’s when I got connected to the slasher for ever more.

Do you have a favorite slasher movie?

Back in 1996, I was at grad school in Florida. It was winter break and my friend, Ryan Van Cleave, dragged me to see this movie. I didn’t want to go because I had a story to write, but it was easier to go than to keep arguing with him. That movie was Scream and I just felt my brain changing. All the homework I’d been doing my whole life was suddenly worth it, because I was getting every joke. It was so challenging, so pleasurable. I went back on my own to see it the next six nights in a row, and I’ve never stopped watching it since.

That’s an interesting choice, because Scream is Wes Craven deconstructing the formula of the slasher. Now, you’re doing the same in your Indian Lake Trilogy. But it’s nearly three decades later, so what do you think you can do differently?

What I was trying to do with My Heart is a Chainsaw is make the reader feel they are being educated in the slasher and how it works… and then show them that those expectations are meaningless, that there is always something new around the corner. I think you have to do that, otherwise you’re walking the same ground everyone else has trodden on. That, to me, is no fun. I don’t think you should write stories that have already been written, or that you know you can write. I like to write novels that, to me, are broken at the level of conception, and then see if I can pull it off.

$14.89

amazon.com

Now that you’ve broken through into mainstream recognition as an author, do you still feel that you can take those narrative risks?

Definitely! I think if I ever stopped taking risks, then I’d stop writing. The one piece of advice I give to students and aspiring writers is always write yourself into a corner, because to get out of that corner, you have to become a better writer. I think it’s the only worthwhile way of moving forward. My Heart is a Chainsaw was a tall, tall order. I wasn’t sure I could pull it off.

What didn’t you think you could pull off?

To surprise people, I guess.

Why and when did you decide to write a sequel to My Heart is a Chainsaw?

I thought it was a standalone novel when I wrote it. But at the end of the first revision, my agent said, “Y’know, everyone is dead by the end. What if you let a few people live?” I dressed up my stubbornness as literary integrity and said, “No, this is Hamlet, with everybody dead on the floor.” But then he convinced me to let a few people survive, and it changed everything. It cued me into how this story is opening up, not closing down. So then I pretended it had always been intended as a trilogy.

What I love about slasher sequels is that when an initial installment is a surprise hit, it makes the audience and the studio demand more. But the story is never originally intended that way, so the crew have to sift through the ashes to find these itty-bitty burnt threads that they can pull on oh-so gently to extract a franchise. I love it when the sequel is unplanned, and that’s the feeling I’m going for in Don’t Fear the Reaper.

You’ve mentioned surprise a few times. One way that these books may confound expectation is in showing far less interest in the killer than the other side of that equation: the final girl.

Yeah, when you go to the Halloween store, there are dozens of Michael Myers masks, but there’s no Laurie Strode [Jamie Lee Curtis’ character in Halloween]. I think there should be. The final girls are the heroes of these stories—they are our model for how to stand up to bullies. But I did want to interrogate that character type. Over the years, the final girl has been moralized, and the result of that process has turned the final girl into some unobtainable ideal. When your model for how to resist bullies becomes unobtainable, it’s no longer a useful model. I wanted to bring the final girl back and make her someone a girl in fifth grade can look at and think it’s not impossible to push back against bullies in her own life.

There’s been much criticism of stories that use violence against women as their catalyst. The slasher seems to be right at the center of that. Is there a way to reconcile the genre with more progressive gender politics?

Yeah, that’s a dynamic we see happen over and over. Hopefully it will become less dominant. That’s why in Chainsaw I had Jade say, “Horror is not a symptom, it’s a love affair.” I wanted her not to be defined by her trauma. I didn’t want to sensationalize it, or make it the keyhole through which the whole plot gets squeezed. That’s why I waited until late in the book, when everything had already reached a crescendo, to reveal what has happened to her. If there are any echoes of that type of trauma in Don’t Fear the Reaper, I leave it off the page. It’s not because I’m flinching; it’s that I don’t want to trivialize or sensationalize it. I don’t want to say that these women are only interesting because of the trauma they have experienced.

$55.00

amazon.com

Both Chainsaw and Reaper feature characters who are obsessed by slasher movies, for good or bad reasons. Are you tussling a little with your own interest in the subject?

Y’know, I hadn’t realized it until you just asked, but I think I probably am. Because when I back off and look at it, I have to acknowledge that here I am, watching high school seniors get ripped apart. I tell myself that I like this as a justice fantasy, but what if I just like to see people get killed or something? [laughs]

That said, there is a lot of moralizing about the slasher. It’s often read as expressing Ronald Reagan values from the ‘80s. But I prefer John Carpenter’s reply to the people who say Halloween is a morality tale. He says that when Michael kills these people who are having sex or doing drugs, he’s not punishing them for that behavior; he’s attacking them when they are at their weakest. I think that’s why the golden age of the slasher was from the late ‘70s to the mid ‘80s. I think it had a whole lot to do with a latch-key kid generation. Kids who knew that when they came home from school, they were on their own until dinner. If they encountered bullies, or got into a Home Alone situation, it was only them. Slashers dramatize that—kids alone, running from scary things.

Your final girl, Jade, is Native American. Is that an important detail for you?

My editor pointed out that My Heart is a Chainsaw is a novel about gentrification. There is this whole new community being built on the far side of the lake in the book, where these people are snatching up pristine forest to build their McMansions. For me, that mirrors the colonial push into America. So I had that operating at a large scope, but it’s also represented at an individual level through Jade’s experiences. And it means everything to me, because we’ve never had a Native final girl. There’s a line in my novel The Only Good Indians when someone says, “If you come for a reservation girl, bring band-aids.” That’s what I want to push in a lot of my books, actually.

Whereas in the sequel, Don’t Fear the Reaper, your killer is also Native. Is it important to feature negative representation as well as positive?

It totally is. One of the things I plead to other Native writers for is for more Indian bad guys. If we are always represented as heroes or victims, then that’s another form of violence, another form of essentialism. For us to be a full, deep, real people, or individuals, we have to be bad guys too.

Yet there is a history of horror monstering minority groups. How do you thread the needle: writing a Native villain without perpetuating the prejudice?

By not expressing the same stereotypes onto these Indian bad guys. If Dark Mill South wore a Geronimo headband and swung a tomahawk and gave a big Indian speech with each murder, that would be turning him into a caricature and doing a different type of violence to everyone.

The immediate problem is that you have to define “Indian.” That’s something very dangerous—to have a gatekeeper saying who and what is and isn’t. You can’t go by blood clan or acculturation. In fact, the main reason I set these books in Idaho, rather than Montana or Colorado, is because my previous book, The Only Good Indians, is set on the reservation and includes a smattering of Blackfoot language. I didn’t want readers to think that to be Indian, you have to live on a reservation.

Jade is very distant from anything that would be ancestral homeland. I wanted to show that you can be Native without that. If you’re like Jade and you are born far away, and your only connection to the tribe or the Nation is your father, but he’s a malignant presence and you don’t want to pursue that… are you still Indian? I think most definitely you are. To say you aren’t is to ignore a whole generation of people who were kidnapped and abducted out, and that’s a terrible violence to do to people. I wanted to show that Jade can be just as Indian out here in rural Idaho as she could in Browning, Montana on the reservation.

Is that pursuit of the outsider important in your writing?

Let me think [long pause]. I’m standing here looking at all my books and I think my characters are nearly always outsiders of some sort. I think that’s the way I grew up. We moved every few months, so I was always the new kid in school, and always the only Indian in school. So in a grand way, I could say that I’m into that whole outsider thing, but the truth is probably that I’m lazy and writing what I know, and that’s being the new kid at school.

Now that you have clearly broken through to mainstream recognition, has that changed?

Possibly, but I look at it like a party. Any party I go to, I end up standing in the corner eating a cracker or something. I want to be in the center of the party talking to people, but I never know how. When I used to watch Star Trek: Voyager, I always used to relate to Seven of Nine, the Borg who joined the crew. She would go to these functions on the party part of the ship and she’d always be at one side asking, “Why are you doing this, what’s going on?” I guess all of my life, I felt like a reclaimed Borg. Maybe it’s like that for all writers. Maybe writers are never at the party. Maybe we are always looking and thinking, “What if?”

You Might Also Like