Spygate: How Right-Wing Media Creates a Conspiracy Theory Out of Thin Air

The plot goes like this: During the summer of 2016, on the clandestine orders of then-President Obama, the FBI and CIA hatched an ambitious plan to topple the Trump campaign from the inside. In a scandal of unprecedented scope, Democratic politicians commandeered American counterintelligence resources to spy on their primary political opponent and boost Hillary Clinton's chances at winning the election. The Russia investigation that has dominated headlines for nearly two years is, in fact, a desperate smokescreen conjured up by terrified Deep State actors to conceal evidence of their own wrongdoing, and to frame the president for heinous crimes he didn't commit.

On May 8, the Washington Post reported on the White House's decision to back the Justice Department's withholding of information from House Intelligence Committee chairman Devin Nunes, on the grounds that disclosure would expose the identity of "a U.S. citizen who has provided information to the FBI and CIA." The authors added, though, that the individual had been a source of information used by the special counsel's office—and that it was unclear whether Trump knew this "key fact" when his administration chose to side with law enforcement.

It didn't take long for him to find out. Almost immediately, the right-wing media ecosystem began laundering and repackaging this news item, weaving its constituent elements together with Trumpian talking points until a full-blown conspiracy theory worthy of the president's tweets emerged on the other side. This metamorphosis is what would happen if a word cloud sourced from a Trump rally were used in a giant game of telephone—but one in which the gibberish end result were then broadcast as news to hundreds of millions of recipients.

How did this happen?

May 10

Two days after the initial report, citing to "the Washington Post's unnamed law-enforcement leakers," the Wall Street Journal publishes an analysis by conservative commentator Kim Strassel. "[W]e might take this to mean that the FBI secretly had a person on the payroll who used his or her non-FBI credentials to interact in some capacity with the Trump campaign." Such a development, she writes, "would amount to spying, and it is hugely disconcerting." Strassel continues (all emphasis mine):

[W]hen precisely was this human source operating? Because if it was prior to that infamous Papadopoulos tip, then the FBI isn’t being straight. It would mean the bureau was spying on the Trump campaign prior to that moment. And that in turn would mean that the FBI had been spurred to act on the basis of something other than a junior campaign aide’s loose lips.

This is at once cautious and bold, introducing the salacious vocabulary of espionage to a detail about an intelligence source—but only, she clarifies, if the allegations are true. Strassel does not offer a reason for entertaining her hypothetical, other than her characterization of the players' accounts of the investigation as "suspiciously vague." She is, in the classic style of well-compensated public intellectuals filling up column inches, just asking questions.

That night, other journalists are happy to offer answers. On Sean Hannity's Fox News show, conservative journalist Sara Carter, citing Strassel, tells listeners of “concern that the FBI actually had a spy within the Trump campaign.” Hannity is dumbfounded: “What? What?” he splutters. "Yes," says Carter. Blogs like Gateway Pundit kick off the breathless hyperbole category. "Now we know why the Deep State has been working so hard to take down President Trump and the republic," said the post, linking to and block-quoting Strassel. "OBAMA DEEP STATE HAD A SPY INSIDE THE TRUMP CAMPAIGN!"

May 11

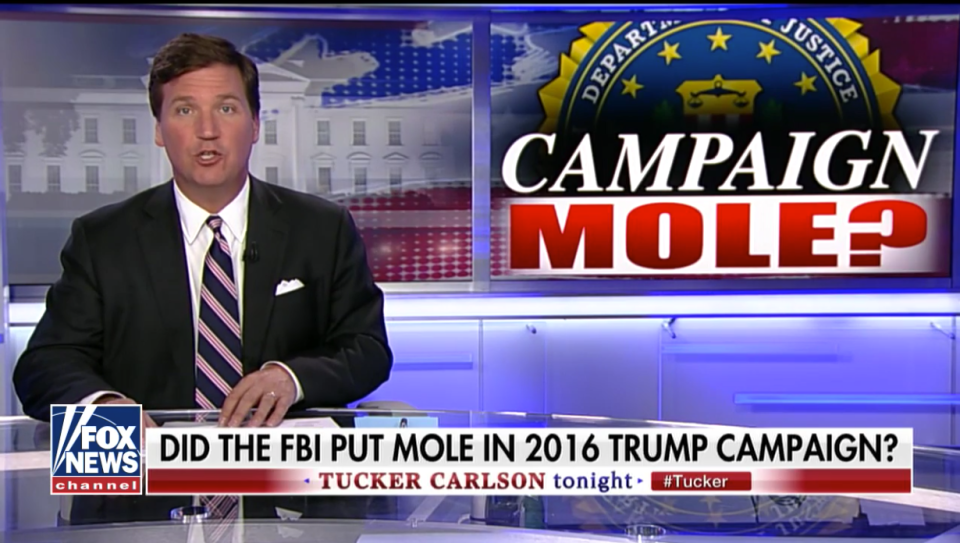

The baton is passed to Fox News, which syndicates Strassel's article and changes the headline from “About that FBI ‘Source’” to “Did the FBI place a mole inside the 2016 Trump campaign?” On Fox & Friends, the president's morning program of choice, Peter Hegseth weighs in, hesitantly at first. "Did the FBI have a spy in the Trump campaign? Just asking the question. There’s an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal about it." Ainsley Earhart quotes at length from the column before positing that it means the FBI and DOJ had someone "paid to go and spy on President Trump."

On his radio show, Rush Limbaugh picks up the thread, encouraging the conflation of the FBI and President Obama. Strassel's article mentions Obama only once, and only in passing. But this is Rush Limbaugh, not a major newspaper; he can say things like this without fear of repercussions.

When I say “the FBI,” I mean the Obama administration. They infiltrated the Trump campaign with a spy, and while they had that spy implanted, they were unmasking and leaking and obtaining FISA spying warrants and conducting criminal investigations of Trump advisers. This is a big deal...For our purposes, folks, the important thing is that the Obama administration infiltrated the Trump campaign with a spy.

The buzz grows louder online. "Did the FBI have a spy in the Trump campaign?" asks Andrew McCarthy, praising Strassel's column as "essential reporting," in a National Review article that published early the next morning. Right-wing blog ZeroHedge makes an affirmative statement—“WSJ: The FBI Hid A Mole In The Trump Campaign”—out of his question. Also citing Strassel, Tucker Carlson refers to a "government spy" and a "mole" sent by "the Obama administration." His guest, NRATV personality Dan Bongino, reveals that he believes there to have been more than one spy, referring to "reporting." He does not elaborate on-air.

May 14

The week begins with lawmakers joining the fray. On Fox & Friends, GOP congressman Ron DeSantis calls for a follow-up investigation into the matter. "I know that we’re actively trying to get the underlying documents that would tell us: Did they spy on the Trump campaign or not?” he asks, implicitly treating the premises of that query as if they were beyond dispute. To Lou Dobbs on Fox Business Network, Matt Gaetz expresses unease with "reports" he'd heard "about potential human intelligence being collected on a rival presidential campaign."

These men are egged on by, among others, Rush Limbaugh, who asserts he knows the identity of the spy that the FBI "put in the Trump campaign," and Hannity, whose radio guest David Limbaugh—Rush's younger brother—opines that "an official policy inserting a confidential source into a presidential campaign" would be "unprecedented" and "worse than Watergate." Like DeSantis, he includes a soft qualifier, though: "If it happened! We have to get to the bottom of it."

May 15

Nunes appears on the Fox & Friends set, hinting that the campaign might have been "set up" by the FBI. “I believe they never should have opened a counterintelligence investigation into a political party,” he explains. And although he at first avoids using the word "spy," his hosts are happy to put it in his mouth. Steve Doocey suggests that Nunes' narrative implies that Trump was "framed," while Earhart adds that "it makes it sound like there was a spy."

Some 12 hours later, Hannity is again agape at the "possibility of an FBI mole that was inside the Trump campaign." He runs snippets of the "stunning" Nunes interview, scarcely able to believe his ears. "The powerful tools of intelligence used to spy on an opposition party candidate, and those powerful tools used against Americans?" he muses. "No, that can't happen here."

May 16

On Laura Ingraham's show, Rudy Giuliani at once broaches the subject of the FBI "possibly placing a spy in the Trump campaign" while admitting that he doesn't know if the gossip is true. The next morning, on Fox & Friends, he’ll again dip his toes in the water before retreating to solid ground. "That would be the biggest scandal in the history of this town—at least, involving law enforcement," Giuliani warns.

He's intrigued by the possibility, though. "Maybe two spies!" he wonders aloud.

Meanwhile, outside the MAGAsphere, a New York Times article helps breathe new life into the conspiracy theory. The authors of that report—an account of the 2016 law enforcement inquiry into the Trump campaign—note that “at least one government informant met several times with Mr. Page and Mr. Papadopoulos.” Referring to the preceding week of innuendo, they characterize this detail as a “politically contentious point, with Mr. Trump’s allies questioning whether the F.B.I. was spying on the Trump campaign or trying to entrap campaign officials.”

As noted by USA Today's Brad Heath, FBI guidelines allow agents to use informants, among many other methods of information-gathering, when assessing whether a matter warrants a full criminal investigation. The Bureau's partial reliance on a "source" here isn't especially remarkable.

And given their knowledge of the Kremlin's election-meddling efforts, it isn't difficult to understand why the intelligence community might have an interest in a campaign's ties to Russia, regardless of the candidate's political affiliation. Marco Rubio—a man not known for being fond of Hillary Clinton—said as much after reviewing the underlying evidence along with the rest of the Senate Intelligence Committee member, which found no secret political motivation for opening the inquiry. “There was a growing body of evidence that a foreign government was attempting to interfere in both the process and the debate surrounding our elections, and their job is to investigate counterintelligence,” he reasoned in comments cited by the Times. “That’s what they did.”

It doesn't matter. One little opening is all it takes. Breitbart, mentioning the May 8 Post story and Strassel's follow-up, proclaims that the Times' report "confirmed" that the FBI ran a "spy operation on the Trump campaign that involved government informants, secret subpoenas, and possible wiretaps." (The article itself mentions only the FISA warrant on Page, but the headline's plural form—"wiretaps"—does its job of making things sound especially ominous.)

May 17

The buzz grows louder as other outlets aggregating the Times report draw the same conclusions Breitbart did. “FBI officials admit they spied on the Trump campaign,” blares The Federalist, which justifies its assertion with a helpful explanatory aside.

This paragraph [in the Times report] is noteworthy for the way it describes spying on the campaign—“at least one government informant met several times with Mr. Page and Mr. Papadopoulos”—before suggesting that might not be spying. The definition of spying is to secretly collect information, so it’s not really in dispute whether a government informant fits the bill.”

Note that the write-up does not actually suggest that the FBI "planted" anyone in the campaign. But by setting out an expansive definition of "spying," articles like this one allow other publications—ones that might not so carefully define their terms—to use the word in that more specific (and more nefarious) context.

It is the National Review's coverage—with an assist from cable news—that finally allows this story to reach the hallways of the Executive Residence. "With the blessing of the Obama White House," writes Andrew McCarthy, again attributing the actions of law enforcement officials to affirmative decisions of the then-president, the FBI "took the powers that enable our government to spy on foreign adversaries and used them to spy on Americans—Americans who just happened to be their political adversaries." He continues:

Obviously, Russia was trying to meddle in the election, mainly through cyber-espionage—hacking. There would, then, have been nothing inappropriate about the FBI’s opening up a counterintelligence investigation against Russia. Indeed, it would have been irresponsible not to do so. That’s what counterintelligence powers are for.

But opening up a counterintelligence investigation against Russia is not the same thing as opening up a counterintelligence investigation against the Trump campaign.

This is the thrust of his argument, and it is nonsensical. McCarthy seems to assume that counterintelligence investigations "against Russia" and counterintelligence investigations "against the Trump campaign" must be mutually exclusive propositions, and that under no circumstances could a Russia-related intelligence probe look at the activities of Russia-related Trump officials. (His analysis is aided by a gross oversimplification of a key provision of FISA.) It would be "irresponsible," he urges, not to investigate what Russia may have been doing. But by virtue of their affiliation with a politician, everyone on the campaign should be insulated from any attendant scrutiny.

Before his column publishes, McCarthy hops on Fox & Friends to promote it. “There’s probably no doubt that they had at least one confidential informant in the campaign,” he says in a strange moment of confidence and timidity. (In a fun, incestuous right-wing media aside, while listing McCarthy's credentials, F&F co-host Brian Kilmeade adds, "Hopefully a Fox News contributor soon.") Not long afterwards, Trump to takes to Twitter to express his outrage, shouting out McCarthy by name for a job well done.

Law enforcement pushback begins in earnest. Sources tell CNN that, no, the source was not placed within the Trump campaign. The Times provides even more details about the timeline, affirming that the informant spoke to campaign members only after the FBI learned of their dubious contacts with Russia. "No evidence has emerged," it reiterated, "that the informant acted improperly when the F.B.I. asked for help in gathering information on the former campaign advisers, or that agents veered from the F.B.I.’s investigative guidelines and began a politically motivated inquiry, which would be illegal."

It's too late, though. Because Donald Trump is President of the United States, the content of his tweets becomes breaking news regardless of its accuracy. "Trump: Justice Department planted spy in 2016 campaign," declares an AP headline that runs, among other places, in the Washington Post and U.S. News & World Report. The body text notes that Trump's "own lawyer" has said that the allegation "might not be true." But for readers inclined to believe what Donald Trump says, or for those who only saw the headline as they scrolled through their phones, it might as well have been proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Epilogue: May 18-20

The next day, the president tweeted again, and again, with grateful acknowledgements for the hard work put in by Fox News personalities Lou Dobbs, David Asman, and Gregg Jarrett.

Emboldened by his boss' declarations, Rudy Giuliani tried to confirm the story and maintain plausible deniability at the same time, telling CNN's Chis Cuomo that although the White House still didn't know if there was a spy in Trump's camp, they had been assured "off the record" of the rumor's veracity. (He added that it might support, in a roundabout way, Trump's baseless allegations that President Obama had him "wiretapped" in 2016.) On Sunday, a few hours after Maria Bartiromo suggested on Fox & Friends "that either President Obama or Hillary Clinton were sort of masterminding all of this,” the president ordered his Justice Department to investigate whether the prior administration had "infiltrated or surveilled" the Trump campaign for political purposes.

With that, the story—that at some point, a law enforcement source communicated with law enforcement officials about various people in the president's orbit—completed its transformation into the staggering revelation that Barack Obama and rogue FBI agents groomed a mole and embedded them deep in the Trump campaign. Strassel's bits of elision that kicked this whole meandering journey off—that an "informant" is not the same as a "spy," and that "being investigated" is very different than "being spied upon"—are distant memories. A new barrage of references to the matter comes every time he turns on the television again.

On Monday, in response to his boss' edict, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein instructed the Justice Department's inspector general to investigate the investigators, a step that could very well derail the original probe into the president's conduct.

This, of course, was the hope all along. "A lot of people are saying," Trump explained to reporters, employing one of his favorite phrases, "that they had spies in my campaign." Technically, he's right. This result is the handiwork of a perfectly-compartmentalized system for manufacturing a lie: Everyone helps to facilitate its creation, but no one is actually responsible for it.