How Sports Memorabilia Exploded Into a Booming Billion-Dollar Business

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was the fifth game of the 1997 NBA finals. Sweating profusely and at time leaning against his teammate Scottie Pippen’s body for support, Michael Jordan somehow scored 38 points while battling a severe case of influenza. Later, while hooked up to an IV drip in the locker room, MJ stuffed his damp socks into his black-and-red Air Jordans and handed them—flu bugs and all—to an elated ball boy.

Presumably the virus was no longer viable 16 years later, when the former ball boy sold Jordan’s autographed “flu game” shoes for $104,765 at auction. The figure garnered headlines back then, long before the spectacular rise in sports-memorabilia prices that would follow the onset of the pandemic. Had the money been invested in the S&P 500 in 2013, it would now be worth $351,000. Instead, the Jordans were auctioned again in June for $1.38 million.

More from Robb Report

Artist Daniel Arsham on His New Hublot Collaboration and the 1986 Porsche He Adores

John Lennon Once Owned This Grand Piano. Now It Could Fetch $3 Million at Auction.

Climate Protestors Vandalized a Portrait of King Charles in Scotland

Once associated with basement hobbyists who jammed baseball cards and game-ticket stubs into shoeboxes, sports memorabilia is emerging as an industry akin to the art market, fueled by testosterone-driven valuations and replete with appraisers, rating agencies, authenticators, specialized insurance, leased vaults, and elite security systems.

Prices have skyrocketed with sale after record-breaking sale, causing many a baby boomer to rue the day their mother threw out their baseball-card collection with the trash.

Anthony Giordano, whose mom tossed his cards when he was drafted into the Air Force at 18, began building a new collection with his two sons when they were young and he was running a New Jersey solid-waste company. In 1991, at his 14-year-old son Ralph’s urging, Giordano bought what’s known as a 1952 Mickey Mantle Topps “rookie” card for $50,000 from a legendary baseball collector named Al “Mr. Mint” Rosen.

Last August, Giordano sold that card, sonically sealed in a hard plastic case, for $12.6 million. He tells Robb Report that the record price—not just for a baseball card but for any piece of sports memorabilia—couldn’t help but remind him of all the Mickey Mantle cards he’d once clipped to bicycle-wheel spokes or traded with friends. “Had we known back then how much they’d be worth…,” he says with a laugh.

The Mantle card and flu-game kicks were no anomalies. At Sotheby’s in September, an anonymous bidder paid $10.1 million—double the high estimate—for a jersey that Jordan wore in the finals of his “Last Dance” season with the Chicago Bulls in 1998. That beat the then-record price for a sweaty shirt (a “game-worn” jersey, in industry parlance) that had been set just four months earlier when an unnamed bidder paid $9.3 million for the one worn by Diego Maradona when he scored the “Hand of God” goal for Argentina in the quarterfinals of the 1986 World Cup. The happy seller was the retired English soccer player Steve Hodge, who had the foresight to trade shirts with Maradona on the field that day after the Argentinean had almost single-handedly defeated England.

In truth, we can’t be certain that these so-called highest prices are actually the topmost, because there is a healthy market in private sales outside of auctions, team stores, eBay shops, and trading conferences. How big is this field? The consulting group Market Decipher estimated the valuation of sports memorabilia globally at $26.1 billion in 2021, while predicting it will reach $227.2 billion by 2032.

Attendance at the annual National Sports Collectors Convention, held in Chicago this July, reflects the explosion of interest from dealers and fans. Just four years ago, the convention counted on drawing roughly 50,000 visitors, says Ray Schulte, director of communications. Those numbers doubled to about 100,000 visitors the past two years, leading the convention to expand its footprint 50 percent this year, from 400,000 to 600,000 square feet.

All this momentum is driving new businesses, such as quality-grading companies, firms that employ high-resolution photos to authenticate game-used merchandise, and insurers who grasp the value of a Yankee Stadium seat signed by Derek Jeter. Vaults located in Oregon and Delaware store memorabilia on behalf of collectors who ship their purchases there to take advantage of those states’ lack of a general sales tax. Some collectors now protect their troves at home with waterless fire-suppression systems that extinguish flames by sucking the oxygen from the storage rooms.

As the sports-memorabilia market has matured, two types of collector have emerged, with lots of crossovers. Some specialize in autographed cards and tickets, while others tend toward acquiring used clothing and equipment. The rules of collecting the two genera are wildly conflicting.

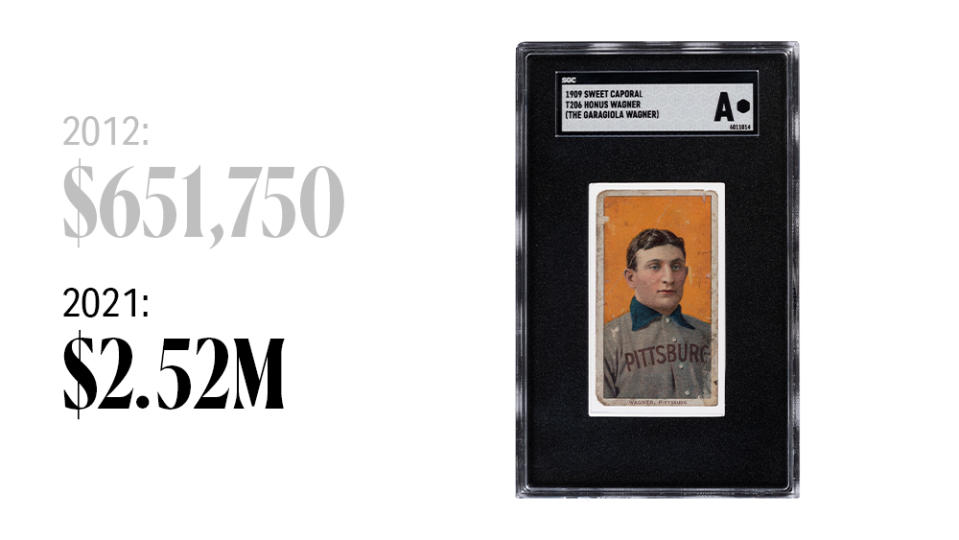

To be valuable, cards should be unblemished as well as rare. The most notable include the ’52 Mantle “rookie” cards from Topps and T206 Honus Wagner baseball cards, issued from 1909 to 1911, of which there are believed to be about 50 in existence. Cards are professionally graded from 1 to 10 by several agencies.

Giordano’s $12.6 million specimen earned a 9.5—nearly perfect: no dings, dents, bent corners, or printing errors.

Pristine condition has a slightly different connotation for game-worn apparel and equipment: Uniforms should never see the inside of a washing machine or a dry cleaner’s. Sweat, dirt, blood, tears—even expired viruses—add value.

Then there’s the weird stuff. Locks of Mickey Mantle’s hair have sold in a sandwich bag as well as framed, and there have even been eager buyers for keys from a Joplin, Mo., Holiday Inn the Mick once owned. Sotheby’s auctioned off a 60-by-48-inch floorboard from the Salt Lake City flu-game court for $17,780.

“Odd stuff brings a lot of money,” says Giordano, who recently lost out on the chance to buy a pack of cigarettes with a photo of Mantle printed on it.

The ones that get away can sting. “I was with my grandson at a baseball game, and I missed it,” he says of the online auction.

The belt Muhammad Ali won in 1974’s historic “Rumble in the Jungle” fight against George Foreman became one of the most expensive pieces of sports memorabilia in 2022.

Goosing interest in sports memorabilia, Netflix this past spring launched a docuseries, King of Collectibles: The Goldin Touch, with episodes tailing Ken Goldin, founder of the auction house Goldin, as he jets around the U.S. dealing in boxing gloves, baseball cards, and a blood-stained flannel baseball jersey while trying to coax his fashion-obsessed daughter into joining the family business.

Goldin has been trading sports memorabilia since childhood and for a time hawked it on QVC and HSN until business slowed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. He founded Goldin in 2012, scoring $800,000 in sales that year. Last year’s revenues, he says, were in the “low-to-mid $300 million” range. It was Goldin who most recently sold the flu-game Jordans, which he had overestimated would go for $3.5 million to $7 million, though the price they achieved was still extraordinary.

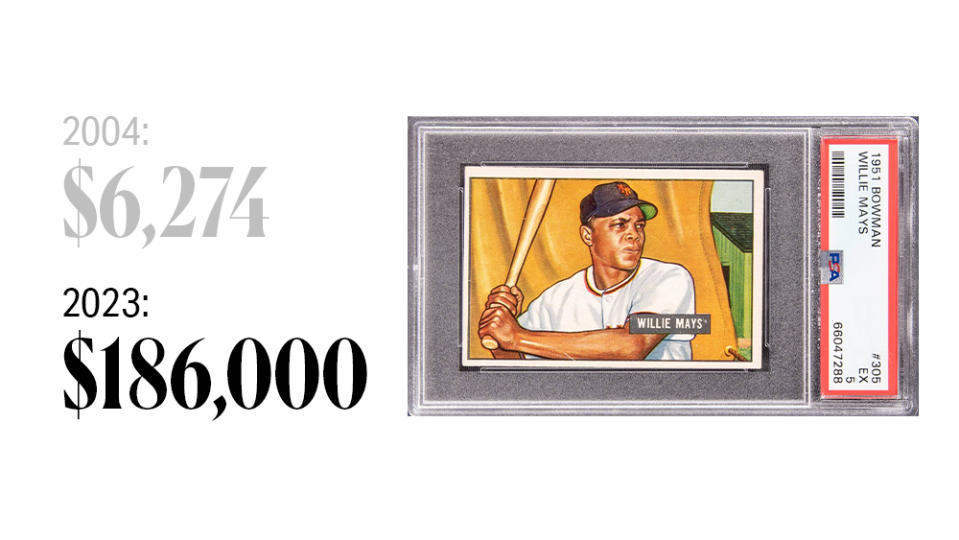

Goldin suggests this particular form of collecting takes root in the hearts of boys—by all accounts, at least 99 percent of collectors in this category are male—when they idolize sports stars. That may explain why baby boomers are more likely to buy a Willie Mays baseball card while Gen Xers and millennials lean toward Magic Johnson and Kobe Bryant.

“I had a billionaire in California spend $3.6 million on a Kobe Bryant jersey,” Goldin says. “That’s the thing about memorabilia collecting—it tugs on the heart. It is literally the shirt off the player’s back.”

For mega sports fans, items touched by their heroes can hold as much historical significance as, say, a first edition of the U.S. Constitution. “To a lot of people, myself included, it makes you feel important,” Goldin explains. “It makes you feel like you captured a moment in a time capsule.”

The big auction houses, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, have both upped their participation in the category as demand has grown, selling items such as the Michael Jordan “Last Dance” jersey, but the field has traditionally been dominated by specialist auction houses run by people who have helped create the market and that cater to newcomers and young collectors by auctioning inexpensive items as well as great white whales.

Goldin’s main rival is Chris Ivy, director of sports at Heritage Auctions, which sold the $12.6 million Mickey Mantle card for Giordano. Like Goldin, Ivy has been collecting sports cards since boyhood. He says the category accounted for $2 million in revenue for the company in 2003, the year he launched the division. In 2022, the house realized nearly $180 million worth of sports memorabilia, with more than $10 million of that from private sales, according to Ivy. This year, Heritage will hold six monthlong catalog auctions and 52 weekly online auctions of less valuable lots, with items starting as low as a few dollars.

“Prior to the 1980s, none of this had intrinsic value,” Ivy says. “It was kids buying bubble gum and putting cards in the spokes of their bikes.”

Prices went soft in the early 2000s and plummeted after the financial crisis, but then the pandemic hit. Men stuck at home in their Brunello Cucinelli sweatpants looked for hobbies. Investment markets became unpredictable; stocks wobbled. Inflation hit.

“People felt that traditional investments like Wall Street were pretty maxed out, so they started looking at alternative assets,” Ivy says.

Take baseball cards: The auction record was broken four times between January 2021 and August 2022, rising from $5.2 million to $12.6 million as examples of the Mantle Topps rookie card and T206 Wagner took turns at the top of the leaderboard.

Ben Thornhill, an investment adviser in Southern California, collects game-used baseball bats, jerseys, helmets, and caps with a strategy that combines investment value with passion. “It’s similar to having a piece of art on the wall,” he says of his collection.

“I love bats that have a ton of pine tar on them and are totally beat-up. I love jerseys if they have a dirt stain on them.”

– Ben Thornhill

He owns bats used by Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle, but a favorite is from George Brett, who was once famously called out for using an “illegal” amount of pine tar to create friction on his bat. That bat now resides in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, but one owned by Thornhill has what the collector believes to be the grooves of the Kansas City Royals player’s fingers preserved in pine tar on the grip.

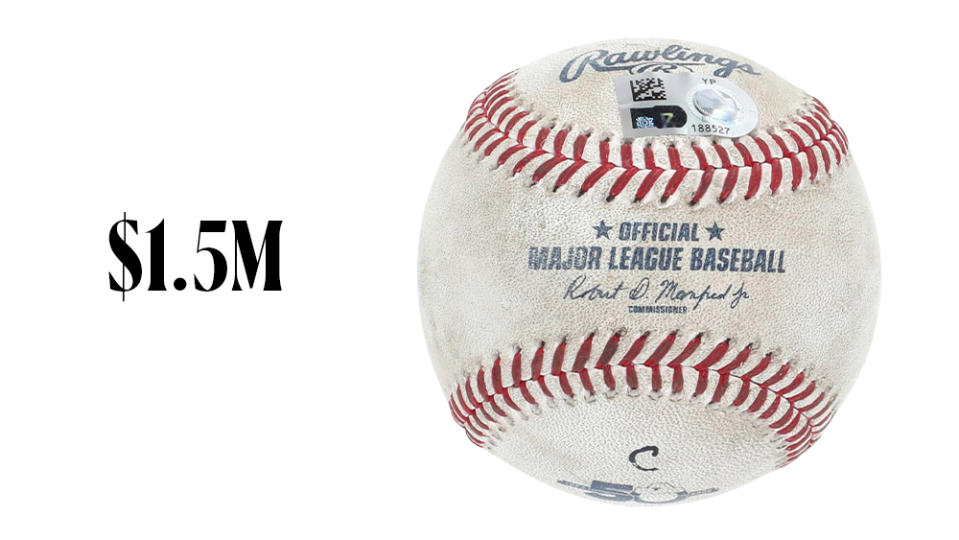

Thornhill senses the market for scarce vintage sports memorabilia is still nascent. “We’re not even at the crest of the wave,” he says. But he raises a red flag for the flood of new autographed merch pouring into team stores and online shops. Major League Baseball’s MLBShop.com is brimming with baseballs, tickets, unworn shoes, and even a framed replica—not game-worn—jersey autographed by Los Angeles Angels pitcher Shohei Ohtani priced as high as $9,999. (As a general rule, an item’s value derives from the object itself—its rarity, condition, historical significance—not the autograph, so don’t waste your money on shiny new balls signed in assembly-line fashion at fan conventions; instead save your dollars for, say, Aaron Judge’s 2022 home-run record-setter, which Goldin sold for $1.5 million in December.)

The rarity that has driven sports memorabilia at the high end of the market already may be becoming a thing of the past. In the old days, players were issued one home and one away uniform per season. Today, pros may go through four jerseys in a week. Teams and leagues get them autographed and sell them alongside all the other merchandise in stores and online as an additional source of income (or sometimes donate them to charity auctions). Collectors speculate on newly manufactured goods signed by young players, driving up prices on yet-unproven athletic careers. “Nowadays it’s produced to sell,” Thornhill says.

If there’s anything scarce in today’s sports-memorabilia market, it’s women—both athletes and collectors. Matt Powers, owner of Power Sports Memorabilia in Lee’s Summit, Mo., recently aired a podcast lamenting that the upcoming National Sports Collectors Convention has not enlisted a single female athlete to sign memorabilia amid 91 stars, among them Walt Frazier, Bill Walton, and Johnny Bench. Powers, the father of two soccer-playing daughters, made a dream-team list of women he’d like to see featured, including Serena Williams and soccer star Alex Morgan.

Schulte, the convention spokesperson, notes that the event’s producers have received the message. “They are currently working on bringing in female athletes,” he wrote in an email to Robb Report. “We hope to make an announcement soon!” Shortly thereafter, the convention booked one: Angel Reese, the national basketball champion Louisiana State University star forward.

“I think the industry is stuck,” says Powers.

Still, the rise of an organized market seems to signify the disappearance of the hobby, with fewer collectors like Chuck Tarantino, a New Jersey telecom executive who began acquiring baseball cards in 1975. He first paid for an autograph in 1982, when he handed $1 to Bobby Thomson, the New York Giant who hit the famed 1951 pennant-winning “Shot Heard ’Round the World,” for his signature at a convention.

“The first time I met Mickey Mantle, he was $7 for an autograph,” says Tarantino, who estimates that he has collected 40,000 signatures, about a third of them for free by chasing the person down. “Ted Williams, Sandy Koufax, Hank Aaron—you name ’em, I’ve met ’em.” Tarantino joined an underground collective of autograph hounds who paid off doormen and airline employees in exchange for intel on athletes’ whereabouts.

“Scottie Pippen is a very elusive autograph,” says Tarantino, who once bought a ticket to a United Negro College Fund dinner in order to ask the guest speaker, Michael Jordan, for his John Hancock. Jordan turned him down. Such was the thrill of the chase.

“It’s not a hobby today,” says Tarantino. “You’re starting to see prices that are mind-boggling.”

Giordano, who sold the record-breaking 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle “rookie” card last August, thinks unexploited value remains for those smart investors who’ve done their homework and know their sports history—like the fact that Mantle’s rookie year was 1951.

“One day, the industry is going to wake up and realize the 1951 Bowman card is worth more than the 1952 Topps card,” he says. “It could be the first $20 million card.”

Who has a Bowman?

“I do,” Giordano says.

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.