Spiral Theory Test Kitchen Wants to Change the Way You Taste

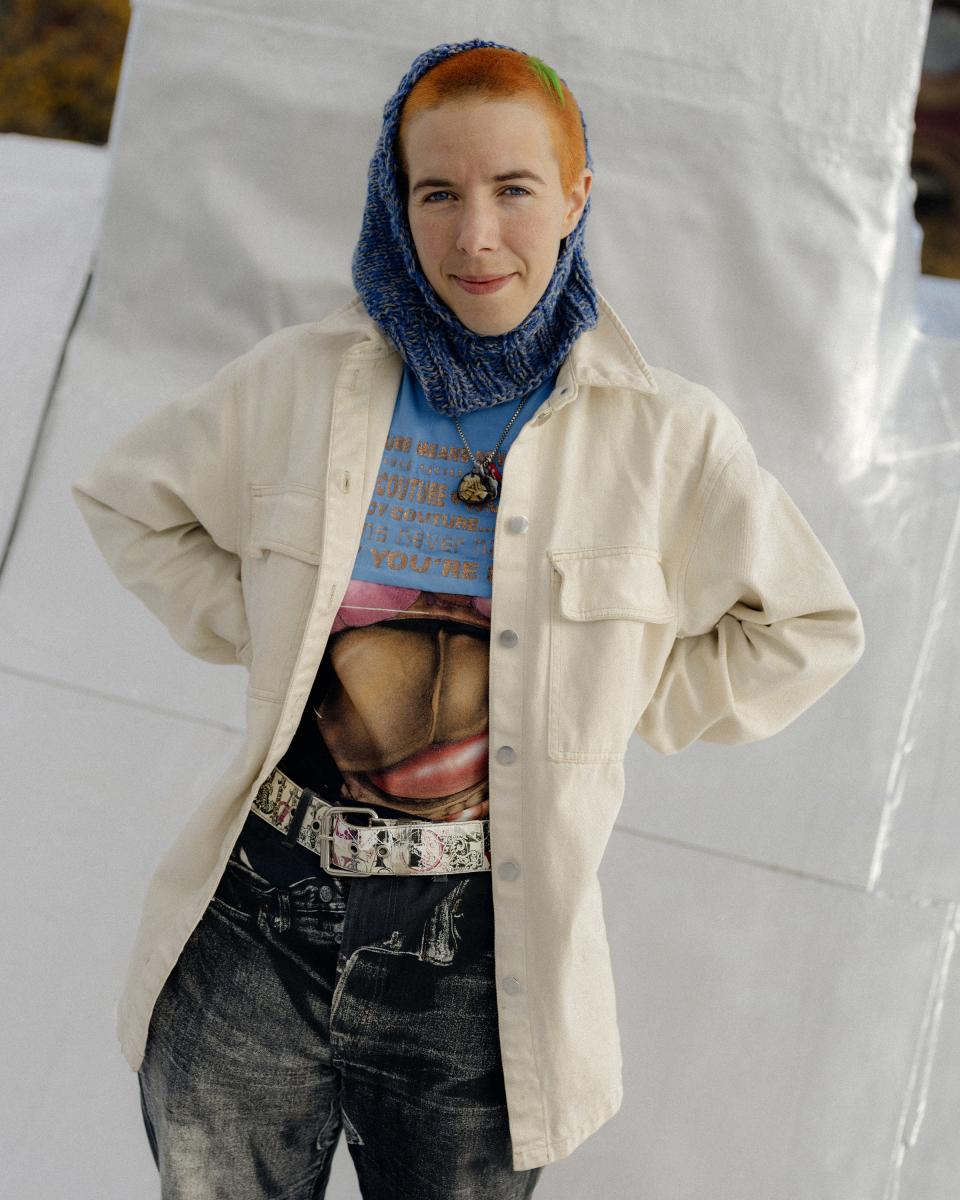

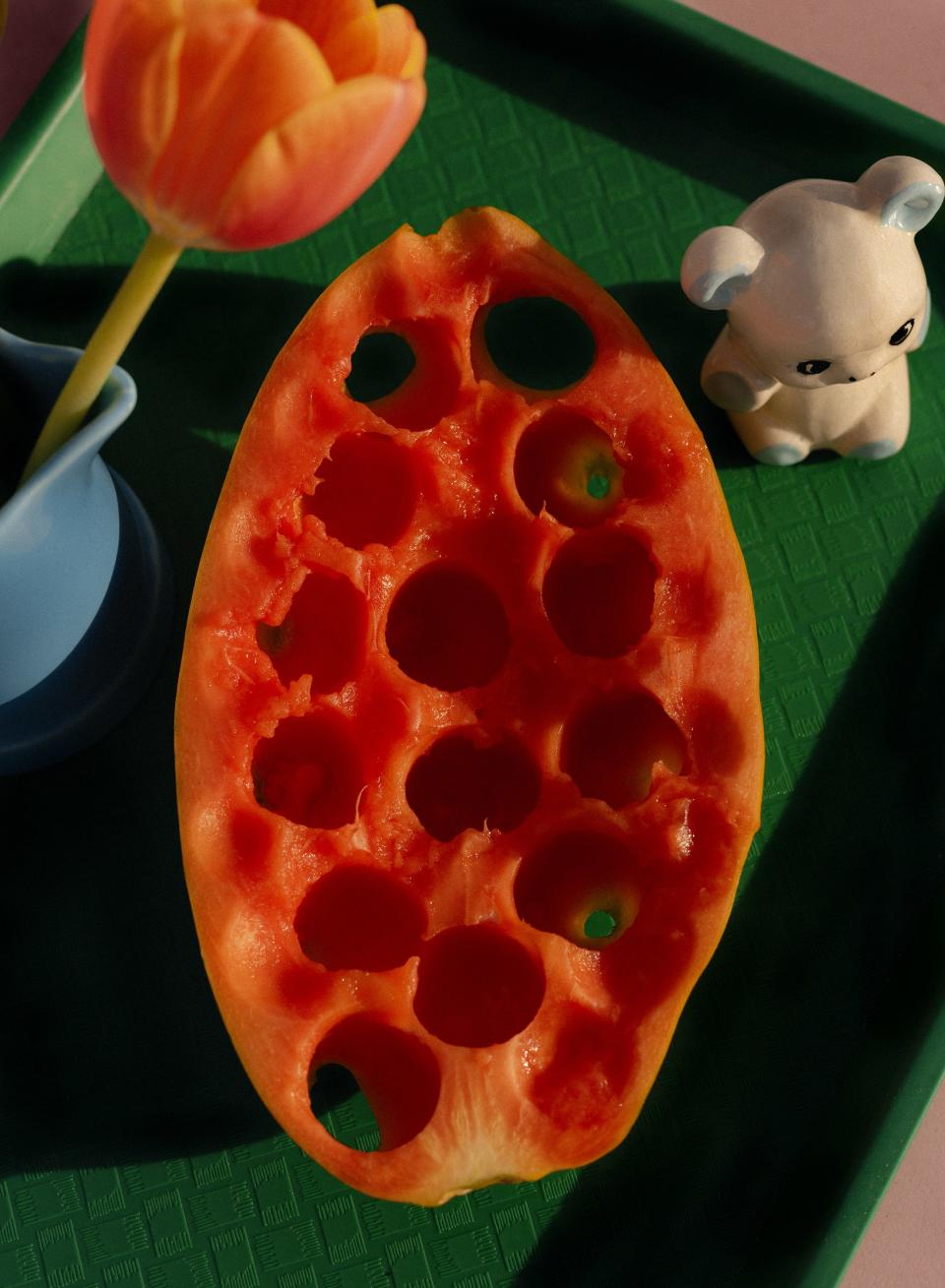

Artists Bobbi Salvör Menuez, Quori Theodor, and Precious Okoyomon (who all use they pronouns) are carefully navigating around each other in the Park Slope apartment where Menuez grew up. Caroline Polachek’s new album, Pang, is playing from a laptop in the corner. Okoyomon’s lace-bibbed toy poodle Rainbow is prancing around, and Menuez and Theodor’s elderly pug, Logan, keeps popping up between feet at inopportune times. Menuez and Theodor now share this apartment, and its well-stocked kitchen (with the usual modest amount of New York City counter space), serves as a testing ground for the artists’ self-described “queer cooking collective,” Spiral Theory Test Kitchen. Their preparation for an upcoming Chinatown art world dinner party involves numerous culinary experiments. During my hour-long visit to the kitchen, I am fed a “buzz button,” technically called spilanthes, which looks like a tiny flower but tastes more like a mouth-numbing Szechuan peppercorn, a kombucha shirley temple (double-fermented tea made with maraschino cherry juice), some scoops of leftover spicy roasted peach ice cream, and swamp grapes that have been fermenting for so long they’ve turned into a bittersweet vinegar. Menuez is busy balling papaya, which they’ll suspend in a delicate rose water aspic the following night, along with the tongue-tingling buzz button and the stringy bits of a corn husk, a riff on the unappetizing idea of what it’s like to discover hair in your food.

STTK officially formed a year ago, and the trio has been cooking up mind-altering meals for art galleries and site-specific events ever since. Their work is as much informed by poetry, sculpture, and theory (this even spans to physics—Okoyomon says that recently they’ve been preoccupied with the theory of quantum entanglement) as it is Menuez, Theodor, and Okoyomon’s distinct culinary skills. “Sometimes the ingredients come after the concept, or even the title will come first—that really drives us,” says Theodor. One STTK dinner, served this past summer, was titled Meal Against Ontological Suffering. At another, in a sort of trans-species, almost Donna Harawayian gesture, a lizard was a dinner guest (they served him crickets). The names for each of the dishes for the following evening (one is titled “Beginning where you and me ends, where we don’t so much come but are already here”) cumulatively read like a poem, and if you plant the little paper menu in soil, it will eventually sprout wildflowers. “You’re eating a poem, in a way,” Menuez explains.

STTK’s culinary exploration has caught the attention of the art world, and New York City chefs like Angela Dimayuga—the trio made Dimayuga’s most recent birthday cake, a three layer lemon fig lavender olive oil cake drizzled with black pine syrup—but their work taps into something that’s been missing from the greater culinary zeitgeist. In an era when chefs are increasingly optimizing their food for maximum Instagram posts, STTK pushes in the opposite direction: their creations are intentionally unwieldy, messy, and hard to encapsulate in just a few characters. Their intuitive recipes unfurl with no event horizon in sight, making their dishes almost impossible to recreate. Still, the imperfect aesthetic has resonated online, cutting through the noise of unicorn food and sickly sweet sundaes.

Spiral Theory’s upcoming dinner party is in collaboration with Los Angeles-based food arts non-profit Active Cultures, which posits that food is a vital form of cultural production, and aims to explore the historical underpinnings that arise from this approach. Active Cultures grew from a conceptual dinner party series titled The MSG Club, which was first founded by artist Glenn Kaino and L.A.-based chef Niki Nakayama, and hoped to cut through nostalgia and familiarity to introduce new foods to their dinner guests, potentially (perhaps hopefully) sowing a bit of discomfort in the process. So STTK designed a menu around “food fears” for this New York City edition of MSG Club—specifically the phobias of two special guests at the dinner party: curator Rujeko Hockley, who is currently the Assistant Curator at the Whitney Museum, and director and puppeteer Frank Oz (you might know him as Miss Piggy, Cookie Monster, or Yoda). Hockley has an aversion to papaya, and Oz has a distaste for cucumber. So papaya balls encased in rose water gelatin were added to the menu, along with a cucumber dish that proved intimidating: STTK set cold-press juiced cucumber in the shape of a frozen ball gag to create a dish that’s quickly becoming one of STTK’s signatures. “There’s salt pickled sakura petals, or cherry blossoms, floating in there too,” Menuez says, as well as a ribbon running through it, so you can tie the frozen juice ball around your head for the full effect (Oz, though he tried, couldn’t seem to stomach it). STTK also created a towering fountain centerpiece that set the table with some other fear-inducing kitchen elements, like broken plates, egg shells, and mounds of dirt. “When people taste our food, they’re like, ‘What the fuck is in my mouth?,’” Okoyomon says. I experienced this firsthand—the dinner guest next to me became convinced, after eating a buzz button cocooned inside the rose water gelatin, that she was allergic to it. She couldn’t figure out where the stinging sensation came from. “That’s my favorite thing,” Okoyomon says. “You can’t place it and you don’t know how you got there. It might be something that you eat that night and you remember it later at two in the morning, and you’re like, ‘Fuck, my stomach feels crazy.’ Yeah, it’s because we fucked with your gut.”

The collective has another workspace in Okoyomon’s home kitchen in Bushwick, which Okoyomon says they’ve basically taken over. “There’s 300 ferments in the fridge. None of my other roommates cook anymore,” Okoyomon jokes as they arrange the dozen or so pigeons that they’re serving as a main course for the MSG dinner. They brined the birds in Alligator pepper the day prior, after which they cooked them in manuka honey, 14 other different types of Nigerian peppers, olive oil, chamomile, juniper, and flowers. Menuez tied the birds up in a kinky imitation of trussing, fashioning string around them in the style of miniature bondage harnesses, which dinner guests were expected to puzzle over with their neighbor. “You sit with somebody and you’re working together to undo this thing with their hands. You can’t really eat a pigeon with a fork,” Okoyomon says, to which Menuez responds: “People will try. They always try!” STTK intends to question not just what is appetizing, but also the initial instinct to pick up utensils. “We’re definitely sometimes pushing people’s edge play in a lot of things, whether it be people’s borderline-colonial understanding of what hygiene is—the history of fermentation pushes against that, or even the fact of eating with your hands pushes against that,” Menuez says. “That’s kind of a loaded way to say it, but I think that’s part of what we actually care about: What does it do to a person to have to eat with their hands with someone they might have just met?”

Each STTK member serves as a leader on a meal aspect that corresponds with their culinary histories—Theodor handles pastry, Menuez is a self-branded “fermentation slut,” and revels in the more tedious tasks, like gelatin molds, while Okoyomon often heads up the meat dishes, as they’re the only non-vegetarian in the mix. Okoyomon’s specialties are rooted in their family—they learned to cook from their mother, who owned a restaurant for a time when the family lived in Lagos. “My mother would never call herself a chef—she’s like ‘I do everything I want all the time,’ but she’s the reason I know how to cook.” Okoyomon’s family moved to Ohio when they were 11. They started to push culinary limits once they got to college. For their thesis presentation at the now-defunct experimental philosophy school Shimer College in Chicago, Okoyomon—who studied pataphysics, or the physics of the imagination—subjected their professors and advisors to a series of conceptual dinner parties. “I did this dinner where I filled the floor with water, so everyone was sitting in water, and there were nooses hanging above everyone’s table, and everyone was eating rock soup for the first hour. Everyone’s hands were together and I ran electrical currents through the water system so it shocked everyone every 2o minutes while they ate this pie, and I made this wind tube thing that was blowing in everyone’s face,” Okoyomon says, breaking out into laughter. “That obviously influenced this project.”

Okoyomon also worked as a prep and line cook at famed Chicago restaurant Alinea for two years while they were still in college, where the use of foams and balloons contributed to their perspective that “food can be whatever you want it to be.” The same freeform spirit clearly informs the world of STTK—after Okoyomon found a bunch of Scotch pine cones in a Brooklyn compost pile this spring, they then simmered them down for 10 hours in sugar syrup with Cambodian pepper, rendering them so soft that they eventually started to taste like sticky toffee—but Okoyomon pinpoints major differences in intention. “What we do is completely different because we’re really thinking about the cosmology of what it actually means for food to have a life of its own. There's beauty in [what Alinea does] but then I'm always like, where’s the heart of the thing? Where does that go?”

Theodor’s parents also informed their interest in food. Their father worked in the health food industry, and their mother was trained in pastry; both were vegetarians with a keen interest in cooking. Theodor eventually went on to culinary school and briefly worked in a professional kitchen, but they found the environment stifling. “I then did my own rogue dinners, but I was basically doing it by myself. I did one that was sort of flash mob-y—everything was mobile and we set up a restaurant on the J train. There were sculptures that doubled as plates and we had a view over the bridge, but without collaborators it was really hard,” Theodor says.

Menuez, on the other hand, says that they were one of those “nightmare children who was extremely picky and only ate bland, flavorless foods,” in spite of the influence of their Icelandic mother. “I was exposed to a lot of freaky ferments—I remember my mom eating a lamb head at the table when we’d visit family in Iceland—and just generally the idea of working with things that maybe aren’t inherently appetizing.” Their father also made some unusual choices in the kitchen, which Menuez says they only later came to appreciate (“He’d put hard mochi in the waffle iron.”) Meneuz then became interested in the psychosexual underpinnings of food in the context of their performance art practice. “I did this one piece where it was a body cast, and people ate vodka infused coconut jello off my ass,” Meneuz says. “There’s something perverse and erotic about how we interact with food and where it exists in our psychology, and I just wanted to play with those different associations.”

Midway through their prep day, we sit in the living room to try out some of the Yoruba yam porridge that they’re testing for tomorrow. Much of what STTK makes is a “loving bastardization” of Okoyomon’s mother’s recipes—they view it as a kind of rebirth—and this one is no different. The porridge is a traditional Nigerian dish, the building blocks of which are cassava yam and what Okoyomon first describes as a basic tomato stew. Theodor scoffs at that descriptor. “Actually, it’s not basic at all,” Okoyomon admits, laughing. “It’s 22 heirloom tomatoes, seven different peppers, and then you fry it in palm oil so it gets a richer texture and you add the yams and smush it down. You can add any type of green you want, too.” The dish is topped off with a fermented, dried pig’s heart that Okoyomon has made in a similar style to a Nigerian chicken recipe they grew up with. “My grandmother would go to the market in Lagos in the morning and buy chickens, and my mom would help her dry them out in the sun all day, rub them down with a dry rub, and then cook them. I’m doing it in a similar way, but I’m air drying it to make it more of a jerky and then slicing it really thin.”

This oftentimes semi-obscured complexity permeates their entire project. One of Menuez’s friends described their project well after witnessing one of their dessert tablescapes during fashion week—the five layer cake they made chaotically combined black sesame, pippali long pepper, juniper, sumac, cardamom, peaches, cashews, saffron, Szechuan peppercorns, white sesame, scotch bonnet cantaloupe buttercream, kefir lime white chocolate ganache, passion fruit, tiger figs, husk cherries, hibiscus powder, and edible flowers. “My friend came to dinner and he was like, you guys literally just always go so hard and people don’t even realize. People are usually trying to get away with doing as little as possible and you guys are always doing the most, even when no one finds out.” Sometimes a vinegar in a dish (an ingredient s not even listed on the menu) is from a kombucha fruit fermentation that Menuez has been slowly working on for months, and oftentimes the plates that they set their food are on are homemade ceramics that Menuez molds and fires. “We’ve never done a thing that’s simple,” Okoyomon says. “That would be really hard for us,” adds Theodor. “That would be insane,” Menuez echoes.

Their recipes are so time-consuming and elaborate that they’ve never really recorded them, although they’ve toyed with the idea of writing a cookbook. “That seems so hard to do honestly because it would just end up having to be sort of a poem, because so much of it is feeling-based,” Meneuz says, which provokes Theodor to improvise a sample STTK recipe: “Start with a really strong meditation practice, and then build your friendships over years—that would be the beginning of the recipe, and you’d have to go from there.” They’re joking, but it’s true. “This collaboration feels bigger than just this collaboration—it’s also about the ways in which I want to build intimacy and communication with Precious and Bobbi,” Theodor adds. Okoyomon relates the STTK process to composing a song. “You need all of these crazy things inside it, and it doesn’t matter how many things are in there as long as in the end you’re like, ‘Holy shit, that sounds good.’’’ You just have to take a taste.

Originally Appeared on Vogue