The Specialized Tarmac Is the Razor Edge of Technology

I have to choose the best race bike of all time? OK. Two stipulations: First, I’m choosing for most riders. I’m not trying to please aficionados of Italian design who reject any brand that doesn’t end in a vowel, nor purists who need everything to be handbuilt and obscure. I love those nerds-and their bikes-but this isn’t their story.

Second, I’m going to try to keep emotion out of it. I know: That’s basically impossible when it comes to bikes. But I’m going to try, even though the bike I’m picking comes from a company that can be emotionally polarizing, for several reasons. One is the simple ubiquity of the brand. It turns a lot of people off-kinda like the Yankees. I get it. But those discussions have nothing to do with quality and performance. I mean, hate the Yankees all you want: They’re still the best baseball team in history.

So, in that objective setting, you’re going to have a tough time convincing me there’s ever been a better all-around race bike than the Specialized S-Works Tarmac. I’ve tested hundreds of bikes over the past 20 years, which has only reinforced my fondness for the consistent zip and ride quality of the Tarmac. In fact, when I wasn’t testing bikes, my daily ride for more than a decade has been a Tarmac.

Here’s how the best race bike in the world has stayed on the leading edge of road race technology all these years.

2003

Half Carbon, Half Aluminum, Full Gas. Tarmac E5 • Specialized refers to the E5 as its first carbon frame. That is and isn’t true. The E5 involved a carbon top half bonded to an aluminum lower, in an attempt to combine the stiffness of aluminum with the weight savings and compliance of carbon. Specialized’s first all-carbon frame was the Roubaix, which debuted the following year, though it was developed in conjunction with the E5.

“At that point we didn’t have much experience with carbon,” says Specialized R&D Creative Specialist Chris D’Aluisio, who has worked on every iteration of Tarmac. “We had a lot of experience with aluminum, so bringing those together was good at the time. Carbon bikes then weren’t what they are now; aluminum bikes were where it was at. So, we were dipping a toe in the water of carbon.”

The E5 was very stiff, but it would feel harsh by modern standards. It had an aluminum backbone, after all. And nothing about its straight-gauge head tube inspires confidence (within a few years, tapered head tubes would become more popular for their improved stiffness and handling). Still, by 2005, the E5 was already starting to define the Tarmac look, with that arched cobra of a top tube that would remain a part of the Tarmac design until 2015.

2006

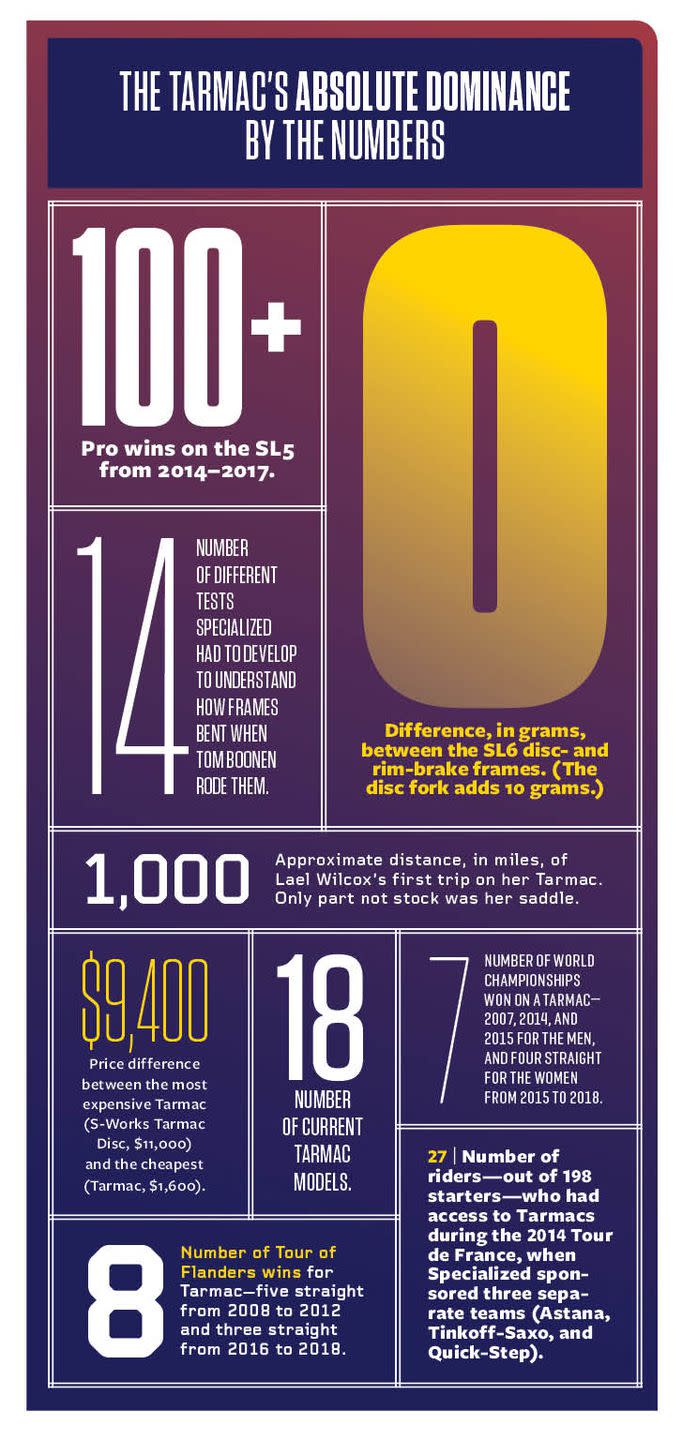

14 Tests • Inside Specialized’s headquarters in Morgan Hill, California, is a lab full of machines designed to twist, compress, stretch, and pound bike frames. One of them is called Test 14, because that’s how many different tests Specialized had to design to replicate what happened to a frame when Belgian strongman Tom Boonen rode it.

Specialized had signed on as the bike supplier for Team Quick-Step ahead of the 2007 season. At the time, the Tarmac SL1 was the company’s premier race bike. It was also the first full-carbon Tarmac. That’s where the superlatives stopped.

“It was unremarkable, if there was ever a Tarmac that was unremarkable,” says Specialized Principal Engineer Luc Callahan. But when Boonen got his first SL, he shared feedback that changed not only the next generation of Tarmac but how Specialized approached frame design and testing overall.

Find 52 weeks of tips and motivation, with space to fill in your mileage and favorite routes, with the Bicycling Training Journal.

“Tom’s a big guy,” D’Aluisio says. “He maneuvers the bike around with his weight a lot more than we were used to. And he was feeling the rear wheel sort of disconnect from the bike.”

Specialized discovered that, while Tarmac had good overall torsional stiffness-a broad measurement of how much the entire frame twists as a single unit, front to back-that global number masked some local issues. Boonen detected that the Tarmac’s rear triangle was not nearly as stiff as the front.

None of Specialized’s existing tests could get the frame to flex in the way he was describing. So engineers built different tests until they finally found one that could recreate it (hence the name Test 14 for the machine that focuses on lateral flex of the rear stays). As a result, they redesigned the rear stays and began testing stiffness at different spots throughout the frame. In that way, Specialized began making sure that what it measured in the lab reflected how the bike would perform under the localized loads of real-world racing.

2008

Specialized Carbon Gets Dialed. Tarmac SL2 • The SL2 is the first Tarmac you could hop on today that would feel comparable to a current carbon racer. It’s not as light, stiff, or aero, but it’s in the ballpark-a bike that worked for Tour riders, Classics specialists, and everything in between.

Based on findings from Test 14, Specialized’s engineers created wishbone seat stays that were custom-tooled for each frame size. Prior to that, they just chopped off the same parallel tubes to fit each size, which didn’t allow for size-specific tuning. SL2 also marked the debut for Specialized of modern construction methods like silicone mandrels, which are flexible inserts that enable stronger and lighter frame sections by pressing out from inside the frame during the curing process (when the laid-up carbon sheets are essentially “baked” into a strong structure).

SL2 was such a massive leap forward that Specialized stuck with it for seven years. The SL3 and SL4 generations were simply iterations on that platform, with tweaks made to weight and stiffness. It wouldn’t be until 2015 and the SL5 that Specialized started over again.

“SL2 was the first carbon bike that really kicked ass for us,” D’Aluisio says.

2012

Rider First • The rear stays of the SL2 project sparked a new approach to designing bikes for Specialized, which the brand codified in 2012 as the Rider First initiative. Rider First is an attempt to deliver the same ride quality for every rider, through different stiffness targets for each frame size.

Historically, the primary difference between frame sizes was geometry. Each frame had the same tubes in the same places, just cut longer or shorter. As carbon engineering advanced, manufacturers began to introduce size-specific layups and shapes, but that was in order to achieve the same stiffness targets at each size. (A longer tube needs more material, different shaping, or both to be as stiff as a shorter tube.)

“Every time we made a bike stiffer, the bigger riders didn’t complain,” D’Aluisio says. “So we just said, ‘Okay, let’s see how far we can take it.’”

They found their limit with Alberto Contador, who, at 5-foot-9 and 137 pounds, could fit inside a leg warmer of the 6-foot-4, 181-pound Tom Boonen. A frame under someone like Contador isn’t subjected to the same forces as a frame ridden by a heavyweight Classics specialist. So, as Specialized added stiffness for their bigger riders-then used those same stiffness targets across all sizes-smaller riders started getting bounced off the back, until, in 2012, Contador said, “No más.”

That year, a team from Specialized went to Contador’s house in Spain. Armed with an SL4 loaded with strain gauges to measure distortions at various points on the frame, the team spent two days putting Contador through a protocol on a local climb-in and out of the saddle, hitting different power zones, riding in his natural style-to understand how a frame responded to light but powerful riders.

Every S-Works Tarmac since then has been built around size-specific stiffness targets. Tuning each size individually means a 140-lb. rider on a 52cm frame and a 180-lb. rider on a 58 will experience a much more comparable ride from their respective bikes.

2015

Leading Out Disc Road. Tarmac SL5 • The bike that grew out of the testing with Contador was the first to reflect a complete application of Rider First from dropout to dropout. In fact, the SL5, which launched in spring of 2014, had three different forks available, depending on size.

Scratch that. There were 15 forks and 30 different frames available, because the SL5 was also the first Tarmac to be offered in a disc brake option, and also came in limited-edition McLaren versions-which used carbon layups and designs created in conjunction with the legendary British car manufacturer. There was a lot going on.

“That was a hairy project,” says Callahan. “But it was a landmark transition for us to add disc brakes.” Specialized claims the SL5 was the first true road race bike to be offered in a disc version. Certainly other manufacturers would object. But I’ll say that I had a chance to test pretty much every top-end road bike with discs that year-and most of the best rim-brake bikes. Nothing approached the SL5.

Despite a radically redesigned frame-including a more aero down tube and a straight top tube-and beefier layup for disc models, the SL5 improved on the handling and responsiveness of the SL4 without sacrificing weight or stiffness. The SL5 felt the way everyone had been telling us for the past 20 years that carbon bikes were supposed to feel. You got on it and you just knew you were going to be faster-if for nothing else than the joy of riding that bike.

2018

The Most Complete Tarmac. Tarmac SL6 • It turns out the SL5 and its predecessors were all pigs. That’s the take if you’re a Specialized product lead or engineer, anyway. And when the new performance targets for SL6 came in, the engineers began initially by adding even more weight. “That’s when Stew and his group came in and said, ‘Nice job guys. Now, get out. It’s our turn,’” D’Aluisio recalls.

“Stew” is Stewart Thompson, who heads up Specialized’s road category and was the product manager for Tarmac during the SL6 development, for which he brought in a more market-driven approach. That is, instead of the engineers pushing the limits and then telling the product team “Here’s the bike we made,” Thompson said, “Here’s the bike the market wants. Go build it.”

“Tarmac always looked nice and rode incredibly well,” Thompson says. “But it was not incredibly light.” Additionally, the aero-road category had exploded. Specialized went all in on the Venge and even built its own wind tunnel. Expectations had changed in cycling. With the product team in charge, the Tarmac SL6 was going to respond to them.

First up: a six-month R&D project. “We bought every competitor aero and semi-aero bike out there,” says Thompson. “We chopped them all up. We did bonding in the wind tunnel, doing everything we could to figure out what we could add without sacrificing aerodynamics, weight, or handling.”

As always, feedback from pro riders was vital, with Quick-Step again playing a major role. Basically, they said they wanted something lighter than the Venge but more compliant on the cobbles than the SL5. The result was a 6.8kg disc-brake bike that Specialized claims is more aero than the first-generation Venge and-for a pro rider-preferable to the Roubaix SL4 for racing on the cobbles. It was the most complete bike Specialized had ever built.

2019

One Bike for All. Women’s Tarmac • Specialized has done a lot to popularize the idea of women’s frames and has invested heavily in developing high-end options for women racers. But for the 2019 model year, Specialized shelved the Amira-a women’s Tarmac platform. In its place is the Women’s Tarmac, which is identical to the men’s Tarmac, save for the touch points (saddle, bar, and cranks). For 2020, even those differences will go away, as the company moves away from gender-specific models to a much more individualized approach: one stock build, with the option to swap out touch points to make the bike fit you.

The shift began in 2012, when Specialized purchased the Retul bike-fitting system, which gave the company access to records from more than 7,000 rider fits. As they pored over the data, they determined that gender variations in frame geometry have been greatly exaggerated. Where differences exist, they can be addressed via stack, reach, and touch points.

This season, the Boels-Dolmans Women’s World Tour team has moved from the Amira to the same SL6 platform that Specialized’s male athletes race. Even ultra-endurance racer and Specialized athlete Lael Wilcox traded in her endurance-oriented Ruby women’s bike for a Tarmac.

“To be honest, I feel more comfortable on the Tarmac than on the Ruby,” says Wilcox, whose “test ride” of her Tarmac was a 1,000-mile epic from Specialized HQ in California to Tucson, Arizona. “It changed the way I ride. In the past, I’d been prone to standing on the bike a lot. The Tarmac taught me to sit for efficiency. It feels like riding a rocket ship.”

Defining Rides and Riders

The Most Exciting Race Ever Won on a Tarmac? / American Mara Abbott breaks away from the field in the final 15 kilometers of the 2016 Olympic women’s road race. But Anna van der Breggen and two other riders give chase and end the final descent just 30 seconds behind, with a flat 10km to the finish line. The three catch Abbott with just 150 meters to go. Then van der Breggen outsprints all of them for gold.

Back-to-back in Flanders / The Roubaix may get the cobble headlines for Specialized, but most riders actually prefer the Tarmac for the Tour of Flanders. Belgian Stijn Devolder rode Tarmacs to victory there in 2008 and 2009 (while racing for Quick-Step, natch).

Two Tours de France in the same year / Alberto Contador rode his Tarmac SL3 to victory in the 2010 Tour de France by 39 seconds over Andy Schleck. He took the yellow jersey after Schleck dropped his chain during Stage 15. Schleck was pissed that his opponents had taken advantage of the mechanical, but Contador had shrugged it off: “Thirty seconds won’t change the race, if you win or not.” When he was later stripped of the victory, the yellow jersey was retroactively awarded to Schleck, who, like Contador, had been riding a Tarmac SL3.

2014 Grand Tour proving grounds / Specialized debuted the Tarmac SL5 just ahead of the 2014 Tour de France, which Vincenzo Nibali won, atop an SL5. Two months later, Contador rode an SL5 to victory in the Vuelta. How’s that for validation?

It’s Peter Sagan’s world(s) / Two of Peter Sagan’s three world championship wins (Richmond and Bergen, Norway) were on Tarmacs. (Doha, Qatar was on a Venge.) Surprisingly, Sagan isn’t heavily involved in bike development. “He’s great for validation, like, ‘yeah this is good,’” says Thompson. “But we don’t get the detailed feedback we get from some other riders.” Kings don’t have to bother with the details.

Rainbow Discs / The first rider to win a world championship on disc brakes? Van der Breggen, in 2018. The bike? A Tarmac SL6.

Tommeke / D’Alusio calls the SL2 “the first carbon bike that really kicked ass for us.” That’s because Boonen kicked the SL1’s ass. No team has been more integral to the development of Tarmac over the years than Quick-Step. Boonen defined that relationship.

El Pistolero / In their drive to satisfy Belgium’s strongest riders, for years Specialized overlooked the particular needs of featherweight climbers-the kind of riders who could deliver Grand Tour glory. It was Contador who got them to deliver the true all-around bike that the Tarmac is today.

('You Might Also Like',)