Spain Without Crowds? It’s Possible Without Leaving Manhattan

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

That upper Manhattan contains the world's largest collection of Spanish art outside of Spain might draw questions about whether you've gone deep into the sherry cask but it's only the surprising truth.

The Hispanic Society of America, a museum reopened in May at 155th and Broadway holds over 900 paintings, 6000 watercolors and drawings and more, including multiple pieces by Goya, Velazquez, and El Greco, and the grandest 14-painting commission ever executed by Joaquín Sorolla. While the museum was undergoing a lengthy renovation in recent years portions of its collection were on something of a grand tour back to the continent, receiving rave reviews on exhibit in London and the Prado. You don't have to take my word for the magnificence of the collection; Miguel Zugaza, Director of the Prado, proclaimed “the wealth of the collections at the Hispanic Society is truly astounding and the remarkably fitting acquisitions of the last few years are a revelation. I think everyone will be surprised by the quality and breadth of these treasures.” If it's worth a trip to Madrid, it's certainly worth a trip to Hamilton Heights.

The museum's director, Guillame Kientz, is intent upon "reintroducing these works to New York" although the first task might be letting the city know it exists.

The Hispanic Society is also hosted in an extremely unusual ensemble of Beaux-Arts cultural institutions laid out in a city block–Audubon Terrace–across the street from Manhattan’s largest cemetery. They were developed by the erudite scion of one of the most era’s grandest robber barons and alone are worth the journey.

The museum's reopening is focused on two main exhibits of works by Sorolla, preeminent turn-of-the-century Spanish painter paired with works of Venezuelan kinetic pop and op-artist Jesús Rafael Soto. Other reopening exhibits focus on the artist Juan de Pareja, Velazquez's slave (eventually manumitted), student, and portrait subject offered in conjunction with the Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibit on his work and life, and exquisite (living) Spanish jewelry designer Luz Camino. And there's much more to come.

We have plenty of Francophiles and Anglophiles and Japanophiles in the US but Hispanophiles are a rarer breed. Some museums have very collections of Spanish art, largely due to the enthusiasm of a few titans such as Frick and Hearst for these works. There are a handful of museums that focus principally on Spanish art (and art of the larger Hispanic world, with some Portuguese elements), such as the Meadows Museum in Dallas. The Hispanic Society is the leading viceroy of them all, both in the size and the breadth of its collection–which attracts frequent praise for not merely featuring the most recognizable names in Spanish art but a broad survey including all sorts of lesser-known great talents.

(L to R) Amantis, Humming Bird, Tall China

How did this happen?

The museum opened in 1908, just a decade after the Spanish-American War, the project of Archer Milton Huntington, the stepson of Collis Potter Huntington, a railroad millionaire. (It was rumored that Archer was actually the trueborn son of Collis, the result of an affair with Archer’s mother before Collis’s first wife died.) A visit to San Marcos, Texas in the early 1870s set off a broader interest in Hispanic culture, with Archer learning Spanish with a tutor from Valladolid (and subsequently even Arabic) before regular trips to Spain.

Hispanic Society Museum & Library

A wealthy stepfather, as everyone knows, is the best predicate for a life of collecting, but Archer took a considerably more serious attention to art than most of the idle rich.

He explained in a diary entry, "I always collected with a view to the definite limitations of the material to be had, always bearing in mind the necessity of presenting a broad outline without duplication… I often astonished my dealer friends by refusing an object which most collectors would have seized upon with enthusiasm." Thus Huntington’s trove became filled with paintings by less famous Spanish artists such as Juan Carreño de Miranda, Antonio de Pareja, Juan Antonio Escalante, Mateao Cerezo, and Sebastian Muñoz.

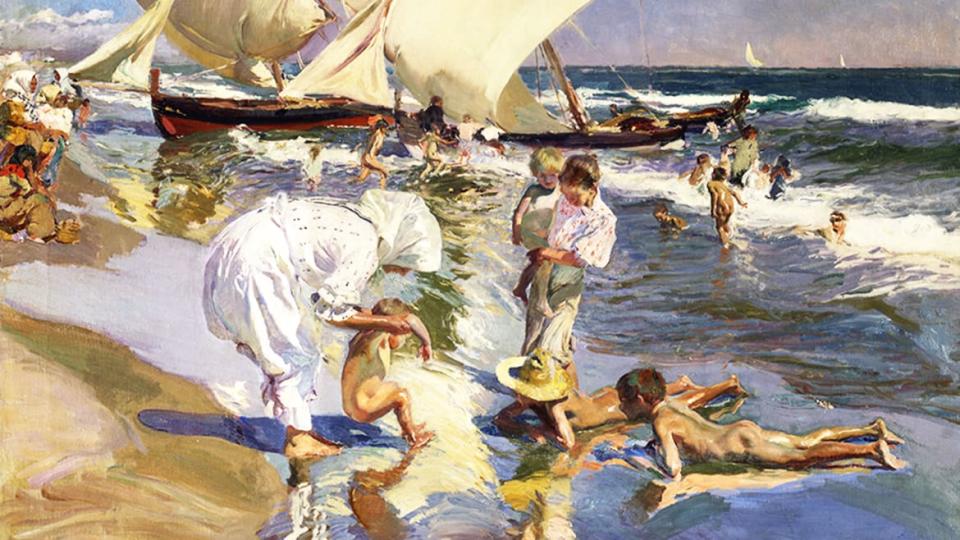

Painting by Joaquín Sorolla

Huntington was also a relatively conscientious collector; beyond books (one of his first acquisitions was a library of 20,000 volumes) he avoided buying paintings in Spain, anxious to avoid being seen as a "plunderer" of this country's treasures. Compare this to say, William Randolph Hearst, who bought a whole Spanish monastery and shipped it in pieces to California, some of which is still lying around San Francisco today. Some of Hungtington's regular dealers seem to have figured out how to work around his noble principles by buying paintings in Spain and presenting them to him with sourcing occluded, but he was generally trying to leave the patrimony back in Spain.

His focus was also distinctly more scholarly than most, with the Society producing a regular stream of monographs and other volumes on Spain. This may have led to a lower profile than other peacocking museums, but the Society once drew quite a crowd, with exhibitions remaining open till 11 PM during its 1908 opening to accommodate droves.

Huntington was also not merely collecting the long-dead but the very-much alive, none more so than Sorolla, whose work he discovered in a London exhibition shortly after the Society opened. He rapidly arranged an exhibit at home and collected avidly, ultimately buying 34 paintings and commissioning the museum's showpiece Visions of Spain series.

Painting by Joaquín Sorolla

Sorolla works occupy the building's main gallery right now along with those of Soto. It is a grand space without stylistic comparison in New York, a double-height gallery surrounded by a terra cotta arcade modeled on a castle patio in Almería. Simone de Beauvoir liked it, writing in 1947:

“I was amazed on going through a door to find myself in the very heart of Spain, the quiet rooms smelt of Spain; they are decorated with majolica, carved paneling and fine stamped leather; hanging from the walls of the gallery which runs round the central hall are Goyda, Grecos, and Zurbarans.."

Sorolla paintings of himself and his wife surround this main floor, beach scenes, one titled "The Peppers" and another of Leonardo Torres Quevado, the inventor of the rigid dirigible (there's one in the backdrop). These are interspersed with pieces by Soto. His best known commissions are large-scale installation art. They can be found from La Defense to the Air France head offices to many locations in Venezuela, and much of it is literally kinetic in moving with the breeze. Most of these do not move but exploit optical illusions to seem to do so.

Sorolla, a supreme talent, was a pal of John Singer Sargent, to whom his work bears some resemblance. He had the misfortune to be a massively talented semi-traditionalist working in the early days of modernism, and his reputation suffered in subsequent decades. Sorolla's trademark was an exceptionally impressionistic approach to light and shadow in works that otherwise don't really belong in that category–it's an exhilarating angle.

Painting by Joaquín Sorolla

=Huntington was a boon to Sorolla; he wrote to his wife, "I think I've met God made man" and he was happy to play Philip II to his Titian, commissioning Sorolla's most ambitious work specifically for the Society, a series of 14 paintings measuring 70 meters wide intended to encompass the whole of that country in oils. Sorolla worked on them from 1914 to 1919, painting or starting nearly all of them en plein air. They are a marvelous assortment, pieces varying from The Tuna Catch in Ayamonte, The Market in Extremadura, Bowling in Guipúzcoa, The Dance in Seville, The Town Council in Navarre, a bullfight and much more. The range is tremendous and style varies: backdrops shift from realistic to nearly Fauvist, shadow and light are rendered in whatever colors he pleases but all work exceptionally well. These were the product of close natural observation and all sorts of care. Some seem to resemble their locations precisely, others engage in some artistic elision; Ávila and Toledo are about 70 miles apart but appear just across a valley in his Castille painting.

The works to be seen are many, some of which were exhibited in the museum's small prefatory exhibitions in a side gallery in recent years. These include an acclaimed El Greco Pietà, Velazquez paintings of subjects from the Duc de Olivares (the sort of Cardinal Richelieu of Philip IV), to a little girl, Goya paintings of grandees and drawings of a bull assailed by dogs.. There are also pieces by Francisco de Zurbarán, the Spanish Caravaggio, and Bayeaux, Goya's teacher and brother-in-law. More recent painters shine as well; Rogelio de Egusquiza a Wagnerian megafan, Catalan luminary Ramon Casas, and Mariano Fortuny y Marsal. There are more Sorollas to come, including a portrait of Louis Tiffany and one of Ortega y Gasset.

Now let's not forget the setting either: the campus has been widely praised and somehow overlooked. Robert Stern, Gregory Gilmartin, and John Massengale called it, in their New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism 1890-1915, "Perhaps the grandest attempt to synthesize the artistic and philosophical goals of the American Renaissance. A verticable acropolis of academic institutions and educational facilities unique outside the context of a university."

With his architect cousin, Charles Pratt Huntington, Archer Huntington kept building museums and institutions, an eclectic assortment that would only seem possible in that era: the American Numismatic Society, the American Geographical Society, a Museum of the American Indian. There are also two buildings for what eventually became the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters by Cass Gilbert and McKim, Mead and White. There's also a church, Our Lady of Esperanza, with a facade remodeled by Stanford White's son and a sanctuary lamp from then-King Alfonso XII.

A number of these institutions left over the years and their buildings have been gobbled up by the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters (which also holds art exhibitions), Boricua College, and the Hispanic Society.

The complex, which looked both dilapidated and unwelcoming as recently as about a year ago, has been making an active effort to reengage with the neighborhood, and the natural accord of a Hispanic Society being located in a Hispanic neighborhood, with new programming aiming to attract neighbors–ranging from concerts to art exhibits–instead of keeping them out. Exhibits loom ahead on Orozco murals and Picasso and the novel La Celestina. It's also always free: subway fare has rarely been so worth it.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.