Is that a spaceship? Delaware house of the future nominated for National Historic Register

When Barney Vincelette saw a Futuro house in the 1970s, he thought space-age design had finally arrived.

“Those of us who grew up in the 1950s and '60s saw science fiction TV shows and movies and some of the science magazines promising radical change with futuristic-style housing,” Vincelette said.

But he didn’t find anything in real life that was living up to that promise until he saw the Futuro house in a catalog.

Most people told him the home looked like a spaceship – a flying saucer.

“It’s the only house I’d ever seen that I wanted to live in,” he said.

After finishing his service in the Air Force, he contacted the company in Philadelphia that made the homes and they referred him to Joe Hudson, a pilot who operated Eagle Crest Aerodrome near Milton, Delaware and also a real estate business. Hudson bought the North American distribution rights to Futuro houses, and received several model homes including one that's still standing at Eagle Crest.

Story about Milton Futuro from 2016: First State Focus: Living in a Futuro House

Vincelette lived in Georgia but that state wouldn't allow the home to be shipped in, so Vincelette moved to Delaware where Hudson sold him a "slightly used" Futuro already set up near Houston, east of Harrington.

That was in 1977 and Vincelette has been living in the flying saucer-shaped home ever since. When he got married, his wife Carol moved in.

Now their home has been nominated for the National Register of Historic Places after the recommendation Oct. 18 from the State Historic Preservation Office at the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs.

The nomination will be reviewed by the National Park Service which administers the program, an honorary yet formal recognition of a property’s historical, architectural or archaeological significance. Benefits of a listing in the National Register include eligibility for federal and state historic preservation programs and tax credits.

No bank would finance his Futuro home

Acquiring the home was more difficult than Vincelette thought. Along with the shipping problems that led him to move to Delaware, obtaining a mortgage and insurance was a challenge.

“Banks wouldn’t work with me on a loan since it’s not a traditional-looking home and it’s not built in a traditional way,” he said. “Insurance companies didn’t know how to insure it.”

Luckily, Hudson was willing to finance the purchase, so Vincelette made the payments to him.

“I think I paid around $13,000 or $14,000 for the house and another $6,000 for the land,” said Vincelette.

He was fortunate to find a home that was already on its own lot because trying to bring a Futuro home to a new site often met with opposition from a town or city.

“They were almost never allowed within municipalities because they didn’t meet traditional building codes,” said Vincelette.

More real estate news: Delaware home sales flat in September, but better than national numbers. What to know.

What’s it like living in the home of the future?

Designed in the late 1960s by Finnish architect Matti Suuronen as a "portable" ski chalet, Futuro houses are made of glass fiber-reinforced plastic, a product first developed for aircraft.

The shell is a two-inch thick plastic sandwich with polyurethane foam insulation between the two layers. Weighing about 5,500 pounds unfurnished, the structure is about two feet off the ground, supported by four sets of steel legs on concrete foundations and a central foundation piece.

“It looks elegant. It has a beauty on its own without other architecture features or anything to decorate it,” said Vincelette. There’s no columns, no dormer windows, no shutters.

Inside, almost everything is curved – the walls, the doors and some of the furniture around the perimeter. The ceiling is like a slightly flattened dome.

“I’ve gotten so used to it, when I go somewhere else like a hotel it’s almost disorienting to wake up in a box-shaped room,” said Vincelette. “I couldn’t imagine living in any other type of house.”

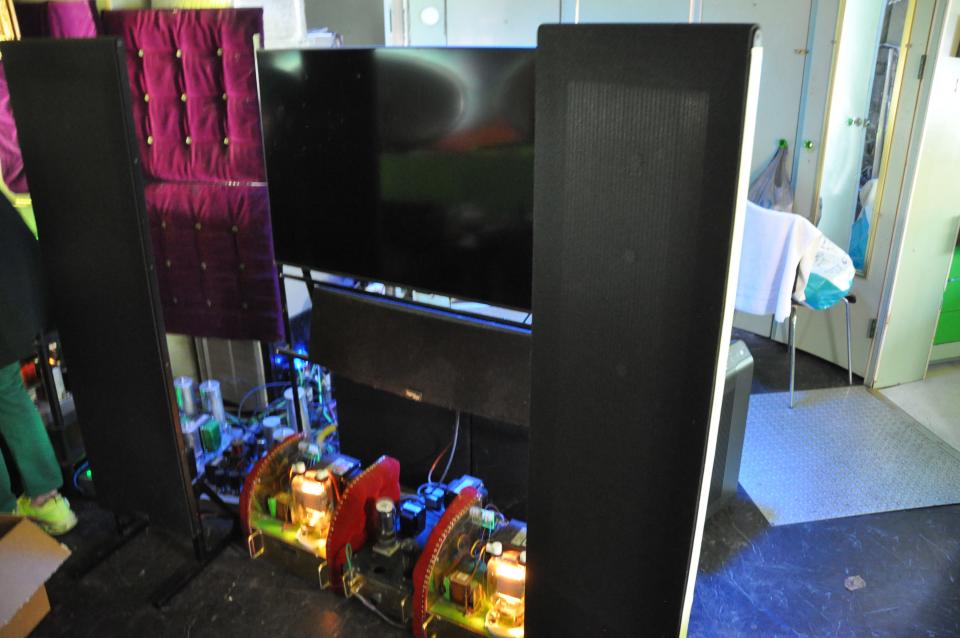

The rounded shape improves the acoustics, he said, and lends itself to two of his hobbies – listening to music, especially classical, on the old-fashioned radio and stereo amplifier system he built using vacuum tubes.

While most of the home is open, the bedroom and bathroom are wedge-shaped with walls.

The one-floor home is small, about 500 square feet – or should that be rounded feet? The building measures 26 feet in diameter and 13 feet high.

“Two people can live here comfortably, or it could be for a couple raising a child and they could wall off another small bedroom,” said Vincelette.

The entrance stairs are part of a door that can be retracted.

He said energy efficiency is better than most houses because of the insulation between the exterior layers which also improves the quietness inside.

“Cooling and heating costs were always cheaper than a standard house until the cost of electricity shot up,” he said.

The two major changes he’s made to the home are to improve energy efficiency.

“It had a fireplace and chimney in the middle, but the chimney wasting heat,” he said. So he sealed it off and added a skylight which improved heat retention.

Then when electricity prices rose dramatically, he installed a geothermal heating and cooling system.

More unique structures: Delaware's 'most iconic building' was saved by an extensive restoration 50 years ago

The nomination for the National Historic Register

Vincelette said when he asked about how to apply for the National Register of Historic Places, one of the people he was referred to was history professor Stephanie Holyfield at Wesley College which was still operating in Dover, now the site of Delaware State University's downtown campus.

In 2018, she agreed to compile the National Register nomination with her public history class of juniors and seniors. They interviewed Vincelette, took photos of the home and began the research.

Her daughter, Valarie Shorter, was a graduate student in public history at James Madison University at the time. She was interested in continuing the work with her mother after the Wesley class ended.

They discovered the Futuro’s design was popular due to Americans’ fascination with space and Cold War-era science fiction along with improvements in aerospace technology.

“It has been important to me to see the project through to the final steps because the unusual architecture and its revolutionary materials merit a place in our history,” said Holyfield. “Futuros are rare, and they capture a singular moment in time.”

She said the design is well-respected and Futuros appear in several European museum collections.

“The architect...aspired to produce something beautiful, cutting-edge and marketable,” Holyfield said. “His work just so happened to…coincide with Americans' pursuit of space flight, which is particularly relevant to Delaware because ILC and DuPont were so heavily involved in the space suit.”

In 1969, Leonard Fruchter was awarded the first license to build the homes in the United States. Based in Philadelphia, his company contracted with a factory to produce them in Atlantic City, as Holyfield and Shorter reported in their National Register nomination.

“A press release issued by the public relations firm Bernard Kaplan & Associates emphasized the Futuros’ versatility, proclaiming that they were ideal beach houses and ski lodges that could accommodate up to eight people,” they wrote.

The average home in the United States in 1968 cost $22,300, “so the Futuro at $19,800 was a sizable investment for a vacation home but still within the reach of many middle-class Americans,” they wrote.

However, Fruchter’s company went bankrupt, mainly because many towns and cities wouldn’t allow the structures, often classifying them as mobile homes. Then the price of oil, from which the plastic was derived, skyrocketed in the early 1970s, dramatically increasing costs.

While fewer than 100 Futuro homes were produced, the homes still have an enthusiastic following after more than 50 years. The Futuro at Eagle Crest Aerodrome is the only other known one in Delaware.

“They have become a part of American popular culture, and they still draw new fans all the time, which is interesting because it’s out of the realm of possibility for most people to own or even stay in one,” Holyfield said.

There’s a Futuro website with information on some of the houses that are still standing. Vincelette has corresponded with the website organizer to include photos and information about his home on the website.

“I hope applying for the National Register calls attention to these houses so they can be protected and preserved,” Vincelette said.

Reporter Ben Mace covers real estate and development news. Reach him at rmace@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Delaware house of the future nominated for National Historic Register