Space Travel and Deep-Ocean Exploration Are Becoming More Accessible

This article originally appeared on Outside

In 2020, former astronaut Kathy Sullivan descended nearly seven miles below the Pacific's surface. When she touched down at a spot on the ocean floor known as Challenger Deep, in the depths of the Mariana Trench, the 68-year-old became the first person to visit both outer space and the deepest known part of the ocean. The next year, multimillionaire video-game developer Richard Garriott, now 61, became the first man to execute the same feat. (Garriott had purchased a trip to the International Space Station in 2008.)

Their rare distinction as intrepid explorers of distant frontiers may not remain unusual for long. Just as tour operators turned quests once reserved for explorers into potential destinations for anyone with the means (read: money)--climbing Mount Everest, treks to the North and South Poles, sailing trips around the world--today's entrepreneurs are now building paths to the ocean's depths and up to the stars. Say hello to tourism at the edge of existence.

Vacations in Space

American entrepreneur Dennis Tito kicked off space tourism in 2001 with his $20 million seat on a Russian rocket to the International Space Station. Several private astronauts have visited the ISS since, including four men who spent 12 days at the station last year as a part of NASA's Private Astronauts Program. Their $55-million-a-seat visit helped mark the arrival of entirely modern space travel.

Elon Musk's company SpaceX oversaw that first all-civilian ISS trip in April 2021, as well as the first first all-civilian orbit around the earth that September. Last year also saw billionaire Jeff Bezos make a suborbital sortie on a rocket built by his space company, Blue Origin, and next year, SpaceX plans to send Japanese billionaire and fashion mogul Yusaku Maezawa on the first-ever private moon orbit. Then there's Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic, a company taking reservations for suborbital microgravity flights, slated to start next year. Thousands have already shelled out for the $450,000 plane-like ride, which will start and end in New Mexico. The 90-minute experience will take travelers up 50,000 feet before boosting into space to experience a few minutes of microgravity.

SpaceX's earth orbit was "the first purely tourist-oriented sightseeing flight," says Rod Pyle, space historian and author of Space 2.0: How Private Spaceflight, a Resurgent NASA, and International Partners Are Creating a New Space Age. "That really draws a bright line for me that we've moved into space tourism at last after talking about it for decades."

Purely private launches like this are still the minority of annual orbital launches--44 of the 146 orbital launches last year were entirely private, according to the analytics and engineering firm Bryce Tech--but the companies behind them are slashing the cost of spaceflight by increasing the number of trips and improving innovations like reusable rockets.

"How many people would be flying to Europe if they had to junk the plane after each flight?" asks Pyle.

This commercial-spaceflight boom enticed NASA to fund $415.6 million at the end of 2021 to private, established companies that can support the development of commercial destinations in space. This furthered the federal agency's long march toward the privatization of space travel. A congressional act in 2010 had essentially "ended the space-shuttle program and got the United States started on the commercial-cargo and crew paths," says Paul Stimers, a commercial space lobbyist who worked on the legislation.

As a result, NASA funded millions to companies like Boeing and SpaceX to kick-start the transition and launched its own Commercial Crew Program to deepen these partnerships. Thanks to such efforts, the cost of reaching space has fallen significantly since increased privatization, says Phil McAlister, NASA's director of commercial space flight.

Soon, however, a rocket won't be your only avenue to the edge of the atmosphere. Starting in 2024, the Florida-based Space Perspectives and Arizona-based WorldView aim to take travelers up to 100,000 feet in pressurized capsules suspended from high-altitude balloons (which are more commonly used as weather balloons). At this height, riders will be able to see the earth's atmosphere and 1,000 miles in every direction, according to WorldView.

There's no microgravity aspect--a sensation triggered by free fall in flights like the $8,200 Zero-G Experience--as high-altitude balloons move slowly up and down; Space Perspective, for example, says its Spaceship Neptune rises at just 12 miles per hour. It's not cheap, though: the ride will cost you $150,000, whereas WorldView, whose 2024 flights from the Grand Canyon and Great Barrier Reef are already sold out, charges $50,000 a seat.

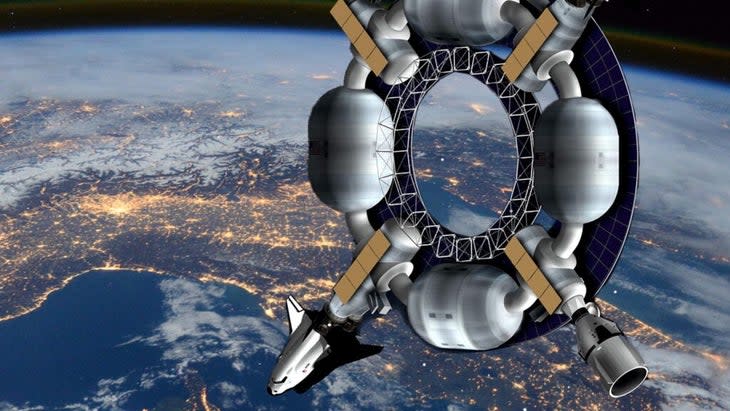

As tourists line up to leave the planet, Orbital Assembly is working to greet them with humanity's first private space center, Pioneer Station. The U.S. company is aiming to have mints on pillows as early as 2027. Pioneer Station is being built for both tourism and business. Bookings will be segmented into a tourist season, a business season, and one for both; this overlapping period could give space tourists opportunities to contribute to cutting-edge science, like bio- or pharmacological research, says Orbital Assembly CEO Rhonda Stevenson.

The microgravity accommodation will be formed by individual pods, called free-flyers, connected by steel trusses in a spoke-and-wheel formation. Any number of free-flyers can be hitched together to form a habitable space station; the current plan is for Pioneer Station to host between 28 and 54 guests. Meanwhile, Voyager Station, Orbital Assembly's planned space hotel, could eventually host as many as 440 guests. Stevenson declined to give a price estimate for a stay at either station, but said a vacation there is likely to span between four days to two weeks and involve activities like microgravity sports.

Assuming adequate funding and launch availability are nailed down, she says they hope to send the first free-flyer to space in 2025. Orbital Assembly projects this sets the stage for a completed Pioneer Station by 2027 and other outposts like Voyager Station to be constructed by the end of the decade. The company is currently in conversation with several space travel providers to arrange transportation to its stations.

"It will be like you have a hotel but you can take any number of airlines to get to that place," says Andrew Lavin, who oversees Orbital Assembly's communications.

Despite how this all sounds--will it really pan out?--space experts view the project as more likely than science fiction. Orbital Assembly's timelines are optimistic to Anita Gale, head of the National Space Society and a senior engineer with Boeing's space program who previously worked on the space-shuttle program, but she thinks sometime in the 2030s is a sound expectation.

"For decades, the idea of space settlement had... let's call it a giggle factor. In the technical community, that giggle factor is gone," she says. "We can talk about living in space, and engineers who are in touch with what's going on in these spaces are saying, 'Yeah, we're gonna do it.' It's a question of when, but it is inevitable. We will be doing business in space."

Deep-Sea Tourism

Going to great depths in the ocean has never seen the public zeal or government support of space travel. While a flurry of rockets reached the moon in the years immediately following the Apollo 11 landing in 1969, more than five decades passed between the first and second visit to Challenger Deep.

Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard were the first people to hit the ocean bottom, in 1960, recording a depth of more than 35,000 feet in a submersible called the Trieste during a U.S. Navy research mission. Famed film director James Cameron became the second person to visit Challenger Deep--in 2012. But both the Trieste and Cameron's submersible sustained damage during their expeditions and could not make repeat trips. Then along came Victor Vescovo, a private-equity investor and retired naval commander, in the possibility-redefining submersible Limiting Factor.

His groundbreaking vessel, built by Florida-based Triton Submersibles, has been the first to repeatedly visit the ocean bottom at such remarkable depths, allowing Vescovo to descend to Challenger Deep an astounding 15 times, become the first person to reach the deepest point in every ocean, and probe the world's deepest shipwreck sites.

"It's the Model T Ford of Hadal submersibles," says Rob McCallum, CEO of EYOS Expeditions, which handles the logistics of Vescovo's adventures. "It's the pathfinder to the last frontier of exploration." (On earth, anyway.)

More than a dozen people visited the trench and conducted scientific experiments with Vescovo, some on donated trips and others thanks to a $750,000 Mission Specialist expedition contribution, making them the first group of travelers to personally pay for a ride to the bottom of the Pacific. Going forward, however, Limiting Factor will be used purely for science under new ownership.

Travelers have also made the deep dive down to the Titanic--nearly 2.5 miles underwater in the North Atlantic--with OceanGate Expeditions. The company has taken more than 30 travelers from Newfoundland to the wreck over the past two years and is currently accepting 2023 reservations for its eight-day adventure. A $250,000 per-person fee helps underwrite the voyage, during which participants support scientists and researchers in the documentation of the rapidly decaying shipwreck and its surrounding environment. They contribute underwater or topside, working on tasks that range from conducting sonar scans from the sub to servicing the vessel post-dive.

"There are very, very few sites that get visited more than once, when you get down to this kind of depth," says OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush. But because people will pay to go to the Titanic, his company can make trips there every year. "The scientists are pretty excited, because you just don't get that opportunity." Previous expeditions produced the first 8K video footage of the Titanic (see video below), discovered an undocumented deep-sea reef and nearby wreck, and gathered data on environmental DNA and coral growth rates for future analysis.

If a trip down to the Titanic in a submersible seems too much for you, OceanGate is planning less intensive options for interested ocean explorers in late 2023 and 2024: a one-day dip off Grand Bahama--starting at a cool $45,000--to support University of the Bahamas research in a deepwater basin, or an exploration of Puget Sound in Washington that costs $20,000, a tab that can be split between you and three friends.

Other wealthy travelers are skipping organized trips altogether, opting instead to play beneath the waves in their own submarines and submersibles. Submersibles are typically deployed from a large boat as, unlike submarines, they cannot maneuver at the surface. They are also substantially smaller--small enough, in fact, to fit on the deck of a luxury yacht.

"There's lots and lots of yachts that have submersibles on board," says Bill Streever, a former commercial diver and author of In Oceans Deep: Courage, Innovation, and Adventure Beneath the Waves. The demand for such vessels within the research community largely disappeared with the advent of underwater drones, he says, explaining: "It just didn't make sense to put human beings down to do what a robot can do without any risk." So submersible companies went looking for a new market and quickly found one in superyacht owners.

Such owners are "looking for the next big thing, and exploring the unknown is the ultimate big thing," says Roy Heijdra, marketing manager at U-Boat Worx, a Norwegian company that began building submersibles for yachts 16 years ago. U-Boat Worx's submersibles regularly descend to 1,000 feet, near the deep end of the ocean's twilight zone; custom builds can be made to descend as much as 10,000 feet; and its five-to-eleven-passenger Cruise Series can explore more than a mile below the surface.

The basic one-seater NEMO model, small enough to tow behind a car, starts at approximately $543,000. Don't want to commit to full ownership? Try a time-share: the brand's new shared-ownership program, rolling out next year in the Caribbean and the South of France, will offer training and partial ownership of a sub for about $154,000.

These vessels are already popular with the cruise crowd.

"Before 2023, there will be 33 newly built expedition cruise ships on the market," says Heijdra, and "most of these cruise ships will have one or two of our cruise subs on board." Crystal, Seabourn, and Viking are among the cruise-liner companies with vessels already carrying at least one U-Boat Worx submersible. And you don't have to be a cruise passenger to get a taste of a U-Boat Worx experience: its Substation Curacao, based on the Caribbean island, offers experiences from the harbor down to 450 feet for as little as $350.

If that's not luxurious enough, what about a full-blown private submarine? No longer the exclusive domain of the military, the Norwegian company Ocean Submarine can build you your own custom vessel, complete with a library, bedroom, chairs with leather seats, a full kitchen, trained crew, and more. Too large to be launched from even mega-yachts, these often set off from private beaches, says Ocean Submarine CEO Martin van Eijk. They are rated to more than half a mile deep.

Ocean Submarine sold six private subs between 2010 and 2020. Then demand spiked, and the company received upward of 120 inquiries from potential customers during the first year of the pandemic. "We have a lot of clients who [are] interested in something where you can safely go down under, have your own eco-assistance and control systems for all the air," says Van Eijk.

For some deep-sea travelers, this exploration is merely a prelude to space travel. OceanGate has partnered with several space-tourism organizations to provide preflight training to the starstruck among us.

"You're in a capsule with some people in a life-threatening or potentially dangerous environment," says OceanGate's Rush. "If they want to go to space, a good training exercise is [to] put them in a setup where they’re in there with four other people for 12 hours, two and a half miles away from anything. If they're going to lose it, that's where they'll lose it."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.