‘Something Extremely Bad Is Happening Here’

Marcus Wheeler lived in a sun-bleached trailer just outside of Tempe, Arizona, but for a long time, he told classmates his home was actually across the street, in an upscale apartment complex. Once the lie was exposed, no one blamed him. How could they? His friends had supportive families, tidy suburban lives. Marcus had neither. His estranged mother lived in the Philippines and hadn't spoken to her son in more than a decade, and his father was a long-haul trucker who thought his son would benefit from a crash course in independence. Marcus was eighteen and alone.

Or mostly alone: He had a girlfriend, friends, and the other runners on the Corona del Sol High School track team. One morning in early 2015, Wheeler arrived at school wearing a bright yellow shirt emblazoned with the logo of Central Arizona College, which had offered him an athletic scholarship. His smile was toothy and broad. Wes Jensen, a teammate of Wheeler's, could see how proud his friend was. But he also knew Marcus was going through some stuff. He'd confessed to Jensen that he'd recently come close to killing himself but that another friend had talked him out of it at the last minute. Jensen hadn't been sure how to respond. Marcus had promised that that part of his life was behind him, so Jensen had let the matter drop.

In the spring, Marcus was kicked off the track team for violating its code of conduct—he'd been playing a taglike game called Assassins, and another student had been injured. Had it been a matter of just losing his scholarship, Marcus might have been able to cope. But around the same time, his relationship with his girlfriend fell apart. Marcus, already in a precarious emotional state, took the breakup poorly. "Help," he tweeted on May 11. "I want my life 3 months ago back." The next morning, he issued a final warning: "There is going to be a suicide in the school right now."

That morning, George Sanchez, a biology teacher, was returning to his classroom with a stack of photocopies when a student alerted him that there was someone in the breezeway with a gun. Sanchez dropped the photocopies, called 911, and helped clear the area. All the while, he kept his eyes trained on Marcus, who was clutching a handgun. "I can't take it anymore," the boy was repeating. "I just can't." There was a look in his eyes that Sanchez would never forget.

As they waited for the police to arrive, administrators ordered the school into lockdown. In a classroom on the second floor, Wes Jensen picked up his phone. Local news stations were reporting that a man with a gun had entered the school. His phone buzzed. A text from his girlfriend: "It's Marcus." Jensen didn't understand. Why would anyone have Marcus at gunpoint? Then it clicked—his comments about suicide, the mess with his girlfriend, his expulsion from the track team. Jensen made a dash for the door, certain that if he could just talk to Marcus, even for a moment, he wouldn't go through with it. He got as far as the door before his classmates piled onto him and dragged him back.

Around 9:00 a.m., Amy Gallagher, a Tempe police officer assigned to Corona del Sol, entered the breezeway and attempted to get Marcus to lower the gun from his temple. "I can help you. I can help," she repeated. "No, you can't," Marcus replied. He swayed back and forth, glanced down one more time at his phone, then pulled the trigger.

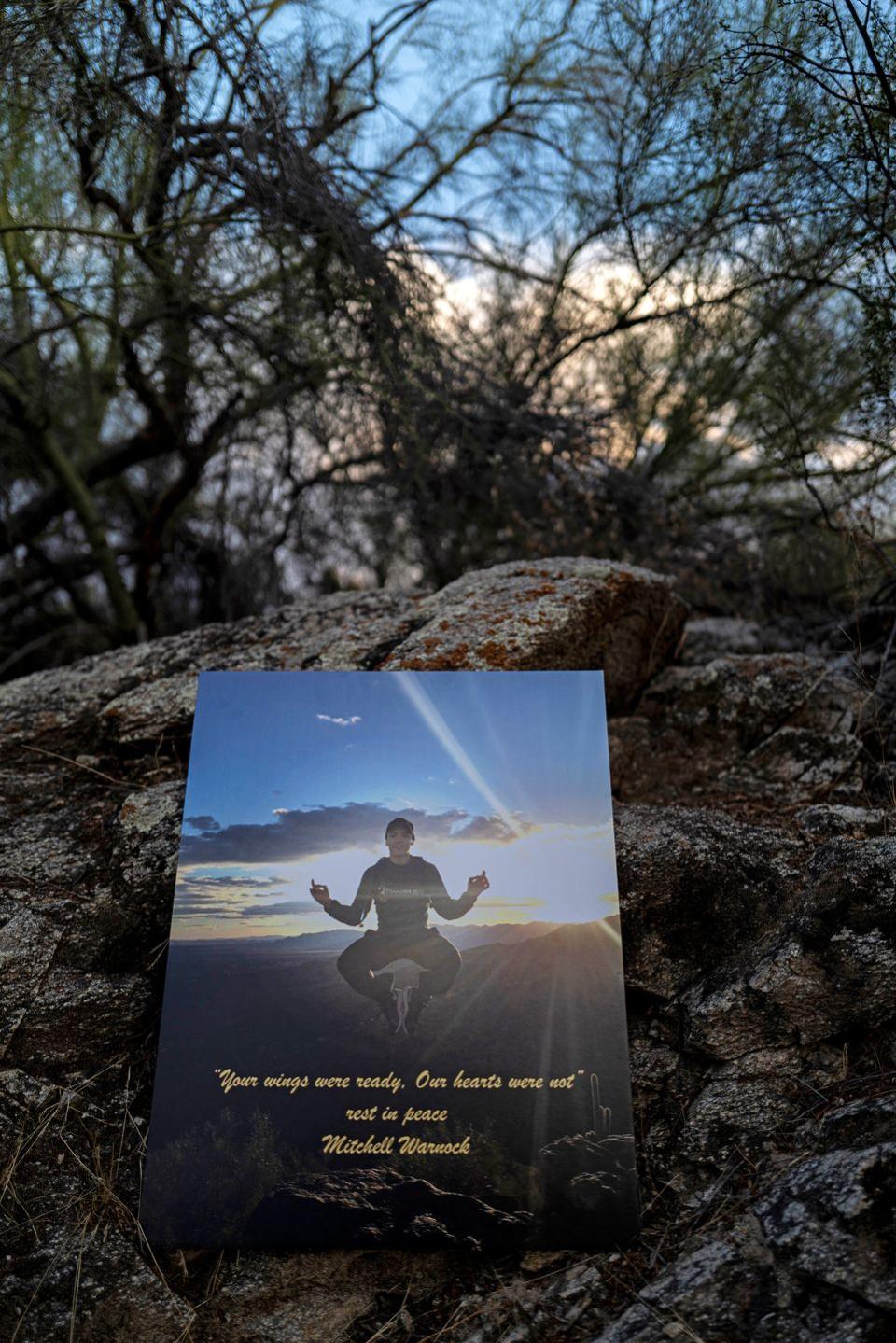

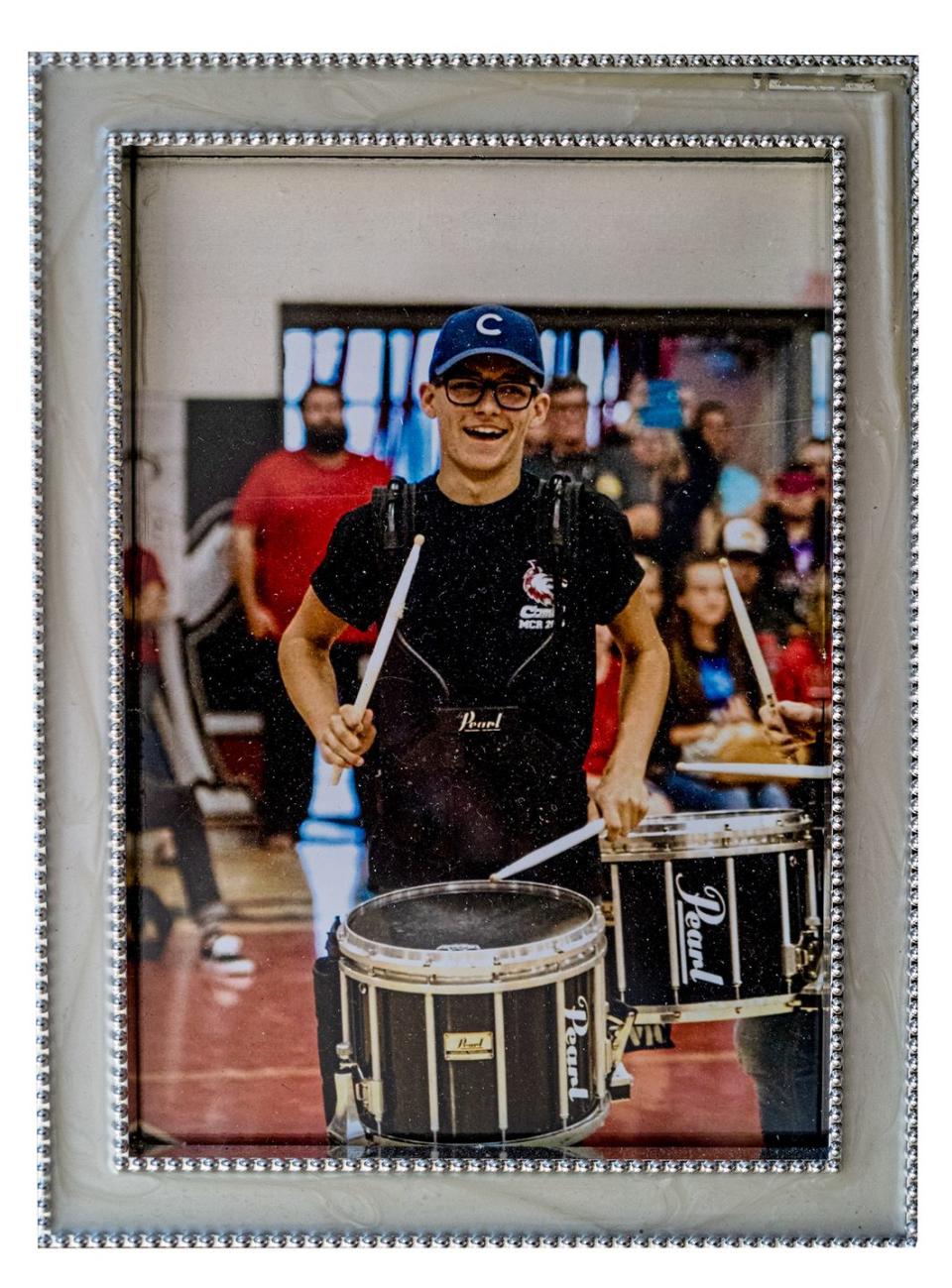

Because the breezeway was still considered an active crime scene, twenty-seven hundred students were routed out another side of the school. Among them was a sophomore named Mitch Warnock. Stocky and strong, Warnock, sixteen, was one of the top pole vaulters in the state; he'd competed alongside Wheeler on the Corona track team and had looked up to the older boy. "I knew Marcus's death was hitting him hard, like it was hitting all of us hard," a friend of Mitch's told me. "But we didn't really get into it that morning, because that wasn't how Mitch was. For his whole life, he put out this image of having his shit together."

Warnock wasn't any more forthcoming with his mother, Lorie, an English teacher at a nearby high school. "I remember he had this shocked look on his face, and I sat him down and said, 'Mitch, what do you think about what happened? What do you think about dying by suicide?' " Lorie told me. "He said, 'Oh, no. That would be the worst thing. That would be'—how did he put it? He said, 'That would be giving up the most precious thing, which is your life.' "

In 2015, the United States was in the midst of what a Newsweek cover story declared a "suicide epidemic." Nearly every demographic was affected: Black people, white people, Latinx people, and especially Native people, whose communities consistently have the highest rates in the nation. Young people, too, like Marcus Wheeler. By the year's end, more than forty-four thousand Americans had killed themselves—an average of one suicide every twelve minutes.

In the weeks and months after Marcus Wheeler's suicide, Lorie Warnock grew concerned about her son. It was obvious to her, and to his friends, that Mitch was more traumatized by Wheeler's death than he'd initially let on. "I think in Mitch's mind, Marcus had escaped. He'd got out of his pain," Tyler Stolworthy, a friend of the two boys', told me. "To Mitch, that was a green light." Although there was a prayer circle for Marcus in the aftermath of his death and a balloon-release ceremony on the football field—and although counselors were made available to the student body—many students wanted more. They felt as if the school was moving too quickly toward normalcy. "It was just, 'This happened, let's move on,' " Stolworthy said. "That was the mentality that everybody had, I guess."

In the fall of 2015, Mitch was summoned to a meeting at school. The message he got was that if his academic performance didn't improve, he shouldn't expect to get into college. Devastated, Mitch transferred all his hopes for college admission onto a pole-vaulting scholarship. To help manage the stress, he started drinking.

One evening the following school year, Mitch showed up intoxicated to a Corona football game, barely able to stand. "I was like, 'Yo, man, are you cool?' " a friend recalled. "Because the security guard at the gate had noticed how drunk he was, just by his actions." When the guard pulled Warnock aside, he exploded—Corona del Sol had a zero-tolerance policy on drinking on school property, and he faced suspension. "I'm going to kill myself," he said. "It's over. It's over! My scholarships are going to be taken away." The police were summoned, and Mitch's parents were called. When Lorie Warnock and her husband, Tim, arrived, they were told what Mitch had said. "Looking at it retroactively, he was repeating the same verbiage that Marcus had used before he died," Lorie said. "Almost exactly the same, like he'd internalized it."

After they got home, Lorie walked in on Mitch attempting to take his own life. She managed to convince him to spend the night at a psychiatric hospital. He was released the next day and seemed to be doing all right, but about a week after that, in mid-October, Warnock attempted suicide again. This time, Lorie wasn't there to stop him.

In December, at a meeting of the Tempe Union High School District's governing board, Lorie Warnock addressed the group. "I was a mess," she told me. "I was like Skeletor. I dragged myself up there and I said, 'I am Lorie Warnock and I am Mitch's mom.' I unleashed. I just went off." She was upset about her son's 2015 meeting and shocked that administrators hadn't been more proactive about outreach to students in the wake of Marcus Wheeler's death. ("The response to what happened to Marcus was beyond inappropriate," Lorie told me.) Soon half the room was crying with her.

The board said it would continue to investigate the issue—"listening a lot . . . learning a lot," as the superintendent described it to me. But to Lorie and many other mothers in the Tempe area, that wasn't enough. "Yes, it was encouraging that people were paying attention, that they were saying they wanted to help," Katey McPherson, a resident of nearby Chandler, told me. "But I thought, What's the exact strategy here? Are we going to be able to do something before we lose another kid?"

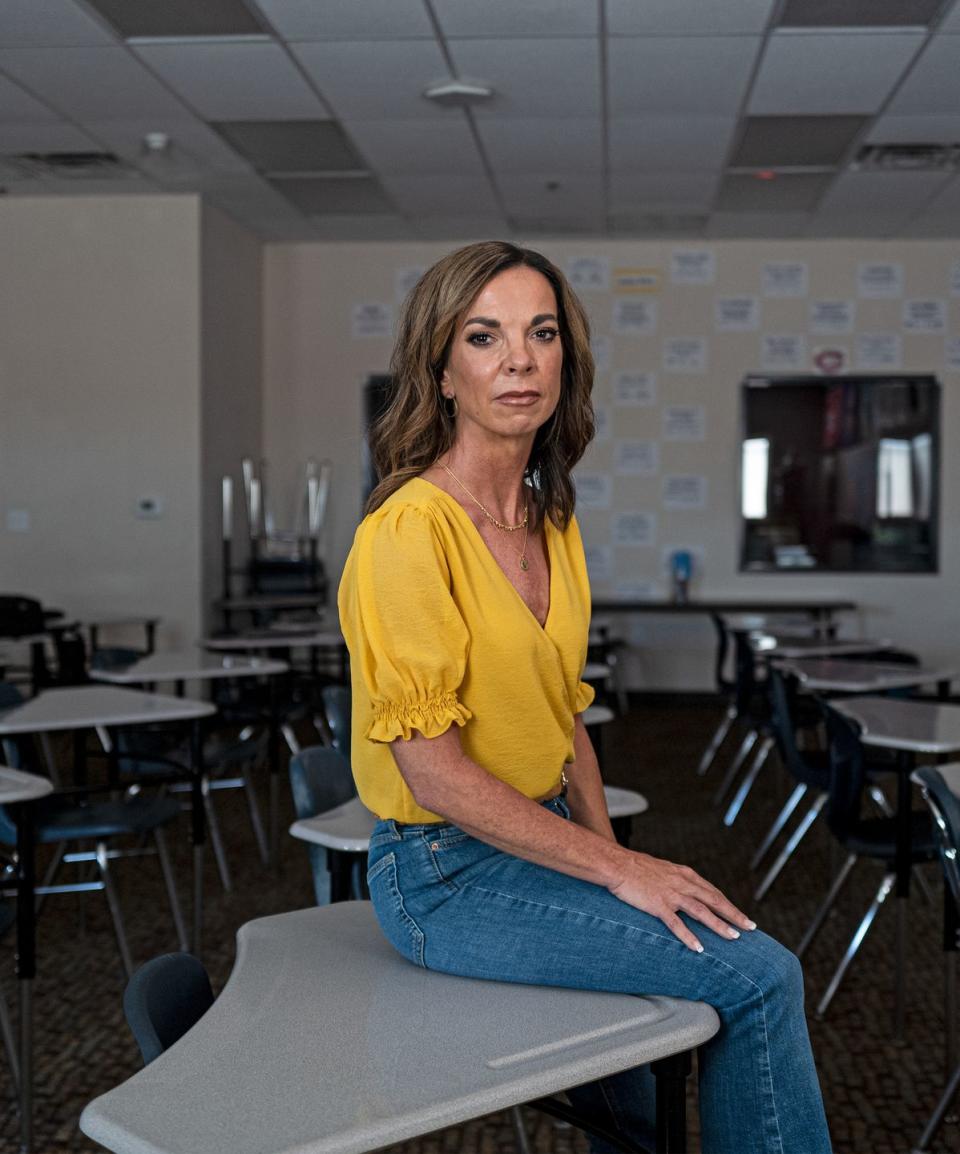

McPherson had spent more than twenty years in education, first as a high school teacher, then as a middle school guidance counselor, then as a vice principal, while raising her four girls. Later, she began advising local schools on policy and curriculum. She'd worked closely in recent years with the Tempe Union High School District; she'd attended the meeting where Lorie Warnock spoke and had made it a point to introduce herself. Warnock, in turn, asked McPherson to accompany her to a subsequent school meeting—as moral support, but also because she knew McPherson shared her frustration with the way the suicides were being handled. "In my mind," McPherson told me, "it could have gone a very different way."

Over the next few weeks, McPherson and Lorie Warnock began brainstorming about how to make sure both students and faculty were heard—and to ensure teachers had the training and resources they needed to recognize signs of mental distress in high school students. In the process, they learned something chilling: Warnock and Wheeler hadn't been the only students at Corona del Sol to commit suicide. Two others had taken their own lives since Marcus's suicide, including a third member of the track team. "I just thought, Yeah, something extremely bad is happening here," McPherson told me. "This is an epidemic. And we'd all better start paying attention."

That suicide might be transmittable is not a new idea: History is rife with episodes of apparently interconnected self-harm, such as the deaths of seventy children in a single Moscow school district in less than two years, starting in 1908, or the drowning suicides of 150 residents of Budapest in 1928. But it is only recently that scientists have confirmed that in certain circumstances, suicidal ideation can travel from person to person like a virus.

One of the first studies on clustering, as the phenomenon is known, was carried out in 1985 by the CDC in two towns in Texas where fourteen teens had died by suicide over a brief period. To map the connections between the deaths, the researchers designed a case-control study, an epidemiological tool traditionally used to figure out why certain people succumb to a disease while others prove resistant. Several patterns emerged. Many of those who'd died had experienced family instability, substance-abuse problems, or a propensity for violence. And several had been connected: Ten victims had been aware of the recent suicides in the community; six had personally known another victim; and four had known two or more victims.

Some of the interventions the CDC researchers proposed were rudimentary and centered on limiting "romanticized" or "sensational" media coverage. As the research on clusters has developed, so too has our ability to respond to the phenomenon in more nuanced and effective ways. Scientists now understand, for example, that most suicide victims later determined to be part of a cluster are young men (as is true of nonclustered suicides, too). They often have a history of mental illness or self-harm. Transmission—a term used frequently in the academic literature on clusters—tends to occur in spaces like schools, where, as a 2019 paper in The Lancet titled "Clustering of Suicides in Children and Adolescents" notes, "social cohesion contribut[es] to the spread of ideas and attitudes."

"If you rewound the clock a few decades, the question was 'Are suicide clusters actually real? Do they exist beyond chance?' " Madelyn Gould, a psychiatric epidemiologist who coauthored the 2019 paper, told me. "Well, we now know that yes, they're real, and they're a public-health problem. So now the focus, for a lot of us, is continuing to understand risk factors"—which, in turn, allows counselors or teachers to gauge which of their students may be at risk of taking their own lives—"and figuring out the manner, or mechanism, that clusters can grow."

A groundbreaking paper published this year in the Journal of Adolescent Health provides some of the most compelling evidence for how those mechanisms operate. For the paper, researchers surveyed students in a community in northeastern Ohio where a suspected cluster of teen suicides had grown to twelve deaths. Of the students who had posted on social media about the suicides, 23 percent reported having suicidal ideation, and 15 percent went on to attempt suicide. "Suicide interventions," the researchers noted, "could benefit from efforts to mitigate potential negative effects of social media and promote prevention messages." To put it another way, social media can be corrosive—it can inspire fear or mimicry—and should be balanced with community outreach.

Recently, Madelyn Gould and several of her colleagues published a set of "key messages" for how to address suicide clusters. One of their recommendations was to respond proactively, with "bereavement support, provision of help for susceptible individuals, engaging with the media proactively, and population approaches to support and prevention."

When several teens died by suicide in Palo Alto, California, in 2014, this was the precise advice that the local schools' superintendent at the time, Max McGee, followed. "I'm not an epidemiologist," McGee told me recently. "But I thought, Okay, this is literally contagious. And I'd spoken to people like Dr. Gould and Dr. Joshi"—Shashank Joshi, a professor of adolescent psychiatry at nearby Stanford University—"and my feeling was that we shouldn't wait for a miracle cure. We should take community action, and do it quickly."

He encouraged the local newspapers to avoid publishing details of how the children had died; he arranged weeks of focus groups and counseling for all students. When a new death occurred—there were four in all—he emailed the entire student body and their parents, and instituted a relaxed class schedule. "And this was very important. Maybe the most important: As soon as we heard about a suicide, we identified the kid's friend group and their siblings and we contacted them right away, to check in on them, to talk to them," McGee said. "Because I knew from the research that these were the people who were going to be most at risk."

Nationwide, the crisis is far from diminished. By one estimate, as many as 13.5 percent of all suicides in the United States are now connected to clusters. And in recent years, fresh outbreaks have been identified in a range of settings: rural Appalachia, the Mormon enclaves of Salt Lake City. But recent research suggests a large number occur among the middle class, in quiet suburbs with good public schools. Places, in other words, like the East Valley of Arizona.

The East Valley extends from the eastern lip of Phoenix through Tempe and out to the ragged volcanic rock of the San Tan Mountains. Comprising more than a million residents and several municipalities, the East Valley nonetheless feels like a single, small town: It shares governments and a newspaper and a population connected through community organizations and sports leagues and strip-mall corridors of Starbucks and fast-food joints. "It sounds corny, but it's a place where everyone at least knows of each other," one East Valley teen told me. "If you're a kid growing up in Chandler, you know people in Gilbert, in Tempe."

Which to many onlookers helped explain the increase in adolescent suicides statewide—from 2009 to 2015, the rate among Arizona teenagers had risen by 81 percent. By May 2017, two years after Marcus Wheeler died, ten teens in the area had ended their own lives, including three in Tempe, two in neighboring Gilbert, and three in Chandler. "There was no doubt in my mind—zero doubt—that this was a cluster," said Max McGee, whom Katey McPherson invited to counsel the school boards of the East Valley on the steps Palo Alto had taken. "And it seemed to me like there was a lot of overlap with what I'd seen in Palo Alto. The pressures of school, of getting into college, of the performance arms race, as I call it." Any roadblock to that success, such as trouble with the police, could send a child spiraling.

To McPherson and Lorie Warnock, the obvious answer was to begin training teachers and educators on prevention techniques. To be proactive, and to get out ahead of the problem before it could worsen. Not everyone was willing to listen. "You'd get superintendents saying, 'Suicide has always been a thing. We're just seeing a bit of an escalation,' " McPherson told me. "Then you had some outright freaking defensive administrators and teachers. But we didn't shut up. Not because we were being rude but because the kids kept coming forward and saying, 'The adults aren't listening. The adults don't understand.' "

In 2017, Tatum Stolworthy, a Corona student and Tyler's sister, founded a peer-support organization known as Aztec Strong. Tatum believed the best approach to dealing with suicide was through destigmatization—to talk about the issue, to bring it into the light. McPherson, supported by Stolworthy's community efforts, and Lorie Warnock approached a state legislator, Mitzi Epstein, with a request that she sponsor a bill mandating suicide-prevention training for all educators in the state. The bill failed. McPherson and Warnock pressed forward, taking meetings with every city official and school administrator in the East Valley who would hear them out. "I became, unfortunately, 'Katey the Suicide Lady,' " McPherson told me.

Obituaries for suicide victims rarely list the cause of death. Using the connections she'd made across the East Valley school system, McPherson started collecting information. "I'd get a link to a social-media post and there'd be a picture of a student who died and hundreds of comments—kids going, 'I just lost another friend.' Or 'I've lost three friends this year,' " McPherson told me. "There were just so many of them, the suicides, and they had occurred pretty closely together." She created a chart on her laptop to keep track. The names on the list weren't just high schoolers. They were recent graduates; they were grade schoolers.

One evening last fall, I had dinner with Joey, twelve, an East Valley resident, and his father, Mike. (At their request, I've used pseudonyms.) Joey was slight and brown-haired and shy; he spoke haltingly, his gaze trained mostly downward. A few years earlier, he told me, he'd met another student whom I'll call Chris. Neither boy had many friends, and they'd formed an instant bond. "We used to gather acorns in little jars and throw them at the playground walls," Joey said. "You know, dumb stuff like that."

"It wasn't dumb," Mike interjected. "You were nine."

Joey shrugged and flashed a half smile. "Still," he said.

Chris and Joey never saw each other outside of school—Chris lived with his custodial guardian, a distant relative, and the man wanted him home immediately after last period every day. Fifth grade was hard for Chris: He was bullied; he performed poorly on tests. "I remember him telling me about his problems . . . how he wanted to kill himself," Joey said. "But I didn't know what suicide was. What it meant."

"Did he?" I asked.

"I know for a fact he did," Joey said, "because his dad had killed himself in prison." Whether Chris knew about the deaths of his peers around the East Valley is unclear. But as Mike recalled, "This thing for a couple years was such a big talking point in our schools and in our area. It was on the front page all the time. All the time."

In 2016, after a class trip to a roller-skating rink, Chris and Joey were hanging out on their school's playground. "We were throwing acorns at the wall," Joey told me. "The bell rang, and I said, 'See you later.' Typically, Chris said 'See you later' first, but that time he didn't say anything at all. I think he just didn't want to lie to me."

The next day, Mike got a text from another parent. Chris had taken his own life. "We spent hours of trying to come to terms with it," Mike said. "Me talking through it with Joey and Joey being like, 'Oh, it must be someone with the same name. It can't be my Chris.' "

"I remember that," Joey said. "It was like, first confusion, then disbelief, then more confusion and sadness. Then anger. Just half a second of anger."

"What were you angry about?" I asked.

"I was angry at his family. I was angry at Chris."

"Why Chris?"

"Because he should have known how much I'd miss him."

"How do you feel these days?"

"I mean, I can get on with my life, and it's not 24/7, but I think about him—" Joey stopped and turned away so I wouldn't see the tear slip down his cheek. "I'm better," he said.

When Tyler Hedstrom was two, his father, Scott, died of cancer, which meant that he was both a stranger and a mythical figure to his son. Ghost and mirror. Everyone was always telling Tyler how much he resembled his dad, and as he got older, he saw it himself, in the grainy photographs his mother, Sheila, kept around their East Valley home. Sheila didn't say it, but Tyler acted like Scott, too. He was sensitive. He felt things deeply but held everything inside. "Freshman year, he took a writing workshop, and all his stories had cancer in them," Sheila said. "I realized that he had an abandonment thing. There was a fear of something horrible happening again."

Sheila and her second husband, Greg, lived with Tyler and his older brother, Alex, in Queen Creek, a desert town at the southern end of the East Valley. Thirty years ago, Queen Creek was a railroad outpost surrounded by sand. But an influx of tech companies, the creation of a regional airport, and the presence of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints helped make the place the fastest-growing community in the state. (Sheila and Greg are not Mormon; they've since moved away from Queen Creek.)

In July 2017, about a week before the start of the school year, Tyler and a friend were parked on a neighborhood street when an officer pulled up, searched their car, and found a small bag of marijuana. "The police's attitude was 'He's not under arrest, but we are going to turn the drugs over to the DA and see what the DA wants to do,' " Greg told me. Alex tried to console his brother by reminding him how much he had going for him: Earlier that month, Ty had gone on tour as the drummer for Anarbor, a rock band from Phoenix; he'd been invited to join them again. And the upcoming school year was an opportunity for a reset. "That calmed him down," Alex said. But then, he added, Tyler and his girlfriend broke up.

To Sheila, who is now friends with Lorie Warnock, the similarities between Tyler and Marcus Wheeler are obvious: Both boys had recently gotten in trouble, which they worried might threaten their future. And they had dealt with the death or the absence of a parent. "I've probably met twenty families that went through what we went through," Sheila told me, and "that is the one common thread I've seen. I'd estimate nine out of ten victims had lost a parent."

But in the summer of 2017, Sheila hadn't yet met the Warnocks or read up on Marcus Wheeler's death. And she was unaware of two additional teen suicides in Queen Creek. "Tyler never talked to us about suicide," Sheila told me. "He didn't talk about self-harm; he didn't talk about the other kids." She swallowed a sob. "To us, he presented as he always was."

Alex Hedstrom suspects that his brother was affected by the growing number of suicides far more than he let on. "I think a seed was planted," he told me. When Alex was younger, he'd gone through a hard time and briefly contemplated suicide. "But I wasn't just thinking about just killing myself," he told me. "I would think specifics, and those specifics came from influences, from different—" he paused and waved his hands in the air. "Basically, from inspiration from shit I'd seen before. You read about it a lot, you hear people talk about it at school, and maybe it gets that much easier to think about killing yourself, you know?"

One evening in July, Tyler posted a despondent message to his finsta, or fake Instagram, the account he reserved for posting the kind of content he didn't feel comfortable sharing under his own name. I'm a loser, he wrote. I'm a piece of shit.

The next morning was an ordinary one for the family. Sheila and Greg went to a Diamondbacks game with her parents, and Tyler had an orthodontist appointment. (Alex was living with his girlfriend at the time.) When they returned from the game, Sheila and Greg were surprised to find the house quiet: no thrash of a drum kit, no music leaking out from under Ty's door. "I had these big plans that we'd all go out to a family dinner," Sheila told me. "I'd get some food in Tyler, and he'd feel better. It would all be better." Instead, bounding up the stairs, she saw her son's body. "I sometimes do the 'what if' thing. Like, 'I'm a nurse. Maybe I could have somehow saved Ty,' " she told me. "But the truth is, as soon as I walked into that room, I knew there was no saving him."

One of the community leaders tracking the uptick in teen suicides in the East Valley was Joronda Montaño, the program director at NotMYKid, a nonprofit that provides counseling to high schoolers in the area. Montaño was one of the first people to identify the deaths as a cluster. Montaño told me that "statistically speaking, this area has long had high teen suicide rates. But it's only pretty recently that you had all these kids looking at each other, saying, 'What exactly is going on?' " I asked what students had said to her about the response from their teachers and school administrators. "One of the things that's come out is that they don't feel that the adults care. And that has everything to do with the way that it's handled when a suicide happens. From their perspective, it's, 'Oh, you don't want us to talk about it.' "

In August 2017, a few days after Sheila found her son's body, another Queen Creek mother, Deanna Bencomo, received a call from the school. Her son, Rudy, hadn't shown up to class that morning. Deanna was alarmed. Earlier that summer, Rudy, who struggled with anxiety and depression, had checked into a psychiatric hospital after intentionally cutting himself. "It's time to tell my story," he'd tweeted upon his return. "On June 15, I attempted suicide. I went to a behavioral hospital and this why I've been gone for a min." He continued, "Queen Creek has experienced a lot of suicidal tragedy. . . . It's heartbreaking and raises questions. Suicide, successful or not, leaves consequences for everyone. I'm dealing with them now [with] my friends, family, and people I don't know. . . . Things are rough. And life is hard. Don't give up. I am not telling you this for sympathy points. But this shit needs to stop."

Now he was missing. "The people at the school, they go, 'His friend called and said he has a rope, and we're worried he's going to try to hurt himself,' " Deanna recalled. "They'd already started looking for him, and I knew the longer it went, the worse it would be." That afternoon, Deanna found out her son was gone.

After Rudy's death, his classmates attempted to erect memorials inside the high school—for Rudy and for the others who'd been lost to suicide. Autumn Bourque, a Queen Creek student at the time, wrote a Facebook post in which she accused school administrators of not encouraging or even supporting the memorials—of essentially wanting to cover up the problem. "I am tired of watching my friends cry, and I'm tired of feeling the pain of loss," she wrote. "Here the school believes that keeping things quiet is better than saying anything at all." The post went viral locally. I spoke to Bourque in September. "It seemed as if the school was embarrassed by the events that took place," she told me, "so tried to hide it." She recalled that when she'd asked why the memorials were a problem, she was told, "It glorifies suicides." (Queen Creek officials told me, "Certain memorials are allowed to stay as long as they stay within guidelines provided by school administrators"; they added that the district has partnered with a local suicide-prevention center, La Frontera Empact, to help "prevent what is sometimes referred to as the contagion effect.")

In 2018, Queen Creek invited Suniya Luthar of Arizona State University to survey the district's teenagers with the goal of understanding why so many students were struggling. In total, Luthar, who'd run similar studies at schools around the country, collected data from more than 1,750 students, ranging from grades nine to twelve. Last March, she presented her findings at a public meeting. Queen Creek's teens, she told the audience, were at or below average levels in several categories, from substance abuse to "rule breaking." But when it came to anxiety and depression, the rates in the town were "elevated and notable." Around 40 percent had reported not having a single adult at school in whom they could confide.

Last fall, I met with several community leaders from Queen Creek in a conference room of a municipal complex in the town's small downtown. The mood was strained. "I came from a district in northern Arizona, and we were bordered by a Navajo reservation—very different dynamic, high poverty. And we had suicides there, too," Perry Berry, the Queen Creek School District superintendent, told me. "I would assume that if you talk to other districts throughout any part of the state, it's happening. Do you know what I'm saying?" But all that proved was the magnitude of the problem, not its absence.

I pressed Berry and assistant superintendent Cord Monroe about the criticism of the town's response to the deaths. Monroe said that the school was bound by the wishes of the victims' parents, some of whom may not want it publicly known how their child died. "It's a delicate balance" he said. Berry added that the district had improved its outreach efforts. "We got a lot smarter about communicating with teachers, communicating with fellow students."

Recently, I printed out a map of the East Valley. Using little red pins, I marked the site of each death, from Marcus Wheeler until the latest, in early August of this year, in an attempt to create a sky-level view of the cluster. It didn't take long for the map to become a wash of red. There were the loose groupings, separated by a few miles or a town line. Then there were the tighter bundles of victims from the same school, or even the same sports team. Forty-seven names in all. Eventually, I ran out of pins.

This article appears in the October/November 2020 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

In September 2019, I had lunch with Katey McPherson at a café in Gilbert. She was about to launch a program called One Gilbert, a suicide-awareness program backed by the then- mayor, Jenn Daniels, a young mother of four who was committed to raising awareness and increasing services in her town. McPherson said she was tired. But she was also cautiously optimistic. Local politicians were giving voice to the problem in a way they never had. And more residents were actively working toward destigmatizing the topic. Lorie Warnock and several of her friends had formed Parents for Suicide Prevention and were distributing pamphlets to families throughout the East Valley. In Queen Creek, Sheila and Greg, Tyler Hedstrom's parents, and Deanna Bencomo got involved with a nonprofit cofounded by Katey McPherson, Project Connect Four, to draw attention to the deaths of local teens. The group had demonstrated outside Queen Creek High School, holding up signs that read, you matter.

As far as McPherson could tell, there had been just four teen suicides in the region in the first nine months of the year, a marked decrease from the year prior. Like many of the East Valley parents I spoke to, she believed the drop was largely due to the programs and policies that schools and governments were putting into place. "Right now, thank God, it's been really quiet," she said. "We're making progress." She knocked on the tabletop. "I hope we're making progress."

Whether the progress will hold is unclear. In response to the coronavirus, many schools in the East Valley have been maintaining online-only or hybrid schedules this fall, and perhaps beyond. The community's various awareness and prevention efforts have been hampered, too. Organizations have done their best to adapt—NotMYKid, Joronda Montaño's group, has been running mental-health- awareness sessions over Zoom that focus on coping skills and self-care; Deanna Bencomo moved her fundraising efforts for suicide-prevention programs online. In September, at a high school in Chandler, Arizona governor Doug Ducey and state health director Cara Christ held a press conference to address the issue. Christ said that it would be several months until they had concrete data regarding the effect the pandemic has had on suicide rates. Ducey noted that researchers had reported a threefold jump in depression since the start of the pandemic. "Many of them are struggling during this time of increased isolation and heightened stress," he added. "And we must be there for them."

There's reason to believe that the East Valley will follow through on that promise. A new bill, S.B. 1468, went into effect at the start of the school year. The legislation, a revived version of the one that failed three years ago, requires school districts and charter schools in the state to provide suicide-prevention training to teachers and guidance counselors working with students in middle school and high school. "Suicides can be prevented when a student displaying warning signs is identified and counseled," Sean Bowie, the young state senator who cosponsored it with fellow Democrat Mitzi Epstein, said in a statement after the bill became law last year. "Our bill provides a critical tool for educators to spot those warning signs in their students who are at risk." It's known as the Mitch Warnock Act.

McPherson attended the signing ceremony. After it ended, she sent me a photograph from the statehouse. In it, the governor, sitting at a desk, is holding up the inked copy of the Mitch Warnock Act while a small crowd looks on. Directly behind him stand Lorie and Tim Warnock. Both are clapping.

You Might Also Like