In “Social Works,” Antwaun Sargent’s First Show at Gagosian, Black Artists Explore the Poetics of Space

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

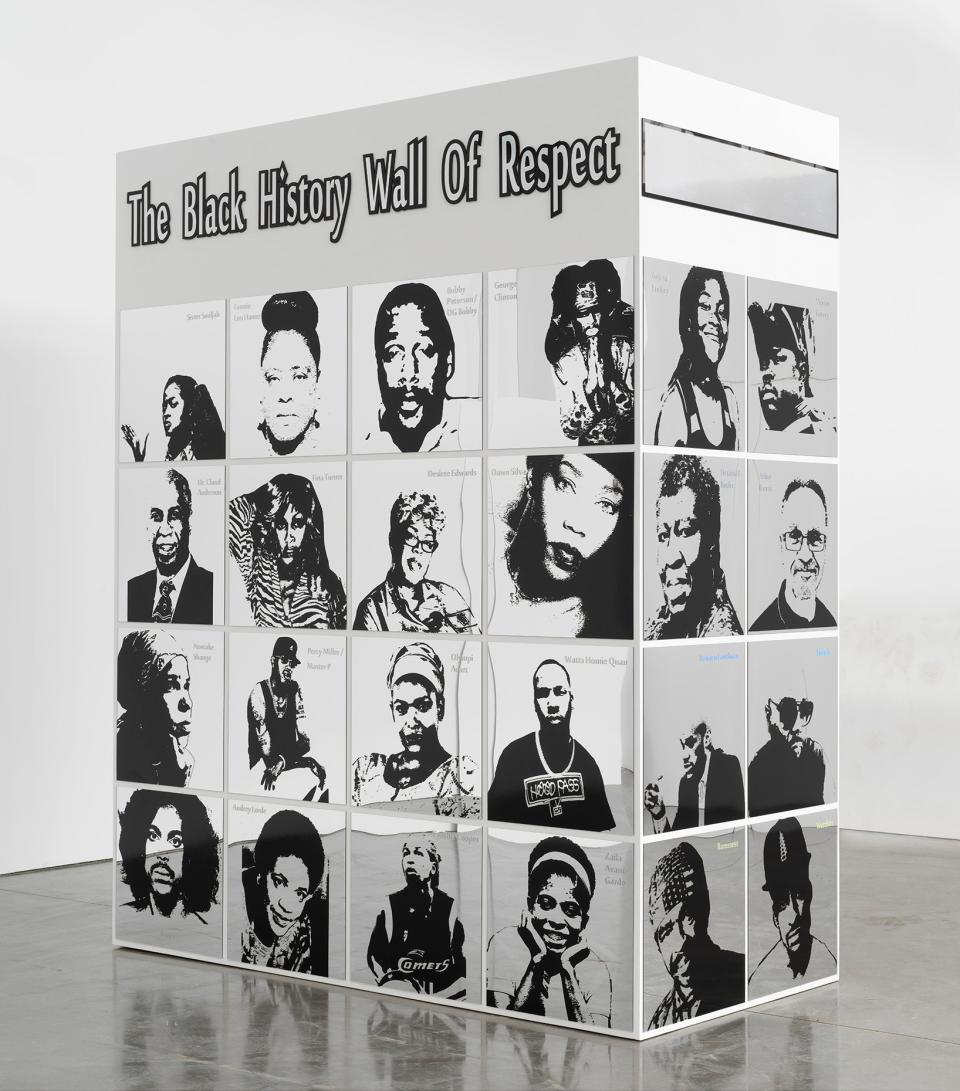

How, in 2021, do Black people occupy and interact within personal, public, institutional, and psychic space? This is the central concern of “Social Works,” a new show at Gagosian curated by the writer and art critic Antwaun Sargent. Comprised of works from 12 leading and emerging artists—David Adjaye, Zalika Azim, Allana Clarke, Kenturah Davis, Theaster Gates, Linda Goode Bryant, Lauren Halsey, Titus Kaphar, Rick Lowe, Christie Neptune, Alexandria Smith, and Carrie Mae Weems—the exhibition, Sargent’s first since joining the gallery as a director in January, mines the fertile intersection between art and social practice within the Black community.

“It’s a pretty ambitious and involved exhibition,” Sargent admits on a recent call. “It’s 12 artists thinking about space aesthetically, politically, culturally, socially, historically, and they’re thinking about that space in painting and sculpture and installation and photography.” As the show relates “to the moment that we’re in”—namely, the pandemic and protests that shaped the last year—“Social Works” “is in consideration of those things, but it’s also a consideration of a longer sweep of history,” he says. Before Black Lives Matter made a case for Black creatives, Black Power gave rise to the Black Arts Movement in the 1960s and 1970s; and from the Civil Rights Movement sprang the Kamoinge Workshop and Spiral. Black aesthetics, sociopolitics, and culture have long been intimately intertwined, and “Social Works” hones in on that fact. “It’s connected to a rich lineage of Black artists who have thought about working inside the community, as opposed to just having normal studio practices,” Sargent says.

In fact, several key figures from that lineage are part of the show. Bryant, for instance, opened the gallery Just Above Midtown (or JAM) in 1974—a place where Black creatives like David Hammons, Lorraine O’Grady, and Howardena Pindell had free rein to show and create—and even now, as the founder and president of the urban farming initiative Project EATS, established in 2009, she keeps questions of space, representation, and inclusion at top of mind.

“The goal of Project EATS is to supply fresh produce to under-resourced communities, and this has been going on for the last decade,” Sargent says. “That’s what I mean when I say the show is about this moment, but it’s also about history. Yes, in this moment a lot of great communal efforts are happening, but there’ve been communities that have had to band together and do that work for a very long time. This show is about acknowledging the ingenuity of these artists who took their practices and enacted them in a community.” Bryant’s installation for “Social Works,” Are we really that different? (2021), pairs an aeroponic and soil garden with live video feeds to probe the parasitic relationship between humankind and nature in our industrial era. “I want to create spaces that are contextual so that we are constantly aware not just of our narrow vision, but of all the things that are influencing and affected by that,” Bryant says. “By conforming to a corporate model of departments, we have increasingly, in my lifetime, lost our ability to understand how we are responsible for the world we live in.”

Figures like Weems, Adjaye, and Gates feel similarly foundational in their perspectives. In her series Roaming (2006) and Museums (2006), Weems—celebrated since the 1990s for her narratively resonant portraits of women of color—pictures herself in Roman piazzas, on side streets and stone steps, and near the façades of the world’s great museums, interrogating architecture and landscape as “edifices of power.” Those spaces, Weems has explained, “are, of course, monumental and they are beautiful … but I’m not confused about what they’re supposed to mean and what they’re supposed to do. Maybe most people are aware of them, too—they just sort of submit to them—[but] I’m of course more interested in challenging them.” For his part, Adjaye—the Ghanaian-British architect behind the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.—is presenting Asaase (2021), his first large-scale autonomous sculpture, which teems with references to buildings like the Cour Royale de Tiébélé in Burkina Faso and Agadez, Niger’s historic city center; and Gates—a potter, installation artist, musician, and urban planner based on the South Side of Chicago—has fashioned a kind of shrine to DJ Frankie Knuckles, a pioneer in Chicago’s house music scene.

While Sargent had already been friendly with many of these artists for years—he began his career in New York as a critic a decade ago—he was pleased to discover, as he assembled “Social Works,” the sticky web of influence and collegiality that linked them to each other. “I called Rick Lowe—a Houston-based artist who’s presenting a series of abstract paintings that commemorates and questions the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921—and I said, ‘Rick, I’m thinking about this show,’ and I named some of the artists I was thinking about,” Sargent recalls, “and he goes, ‘I spoke to so-and-so last week.’ So there are these networks of artists that communicate with other artists working in other communities, so that they can share in trying to build communities that are more equitable and more just that through art.”

Yet a new generation of artists also plays an important role in “Social Works,” looking hopefully toward the future of Black social and creative practice. Five of them are former Studio Fellows at NXTHVN, a New Haven-based nonprofit founded by Kaphar, Jason Price, and Jonathan Brand that advances an “alternative model of art mentorship and career advising.” Positioned as small business owners, Fellows are coached in—among other things—the fundamentals of marketing, networking, and filing their taxes.

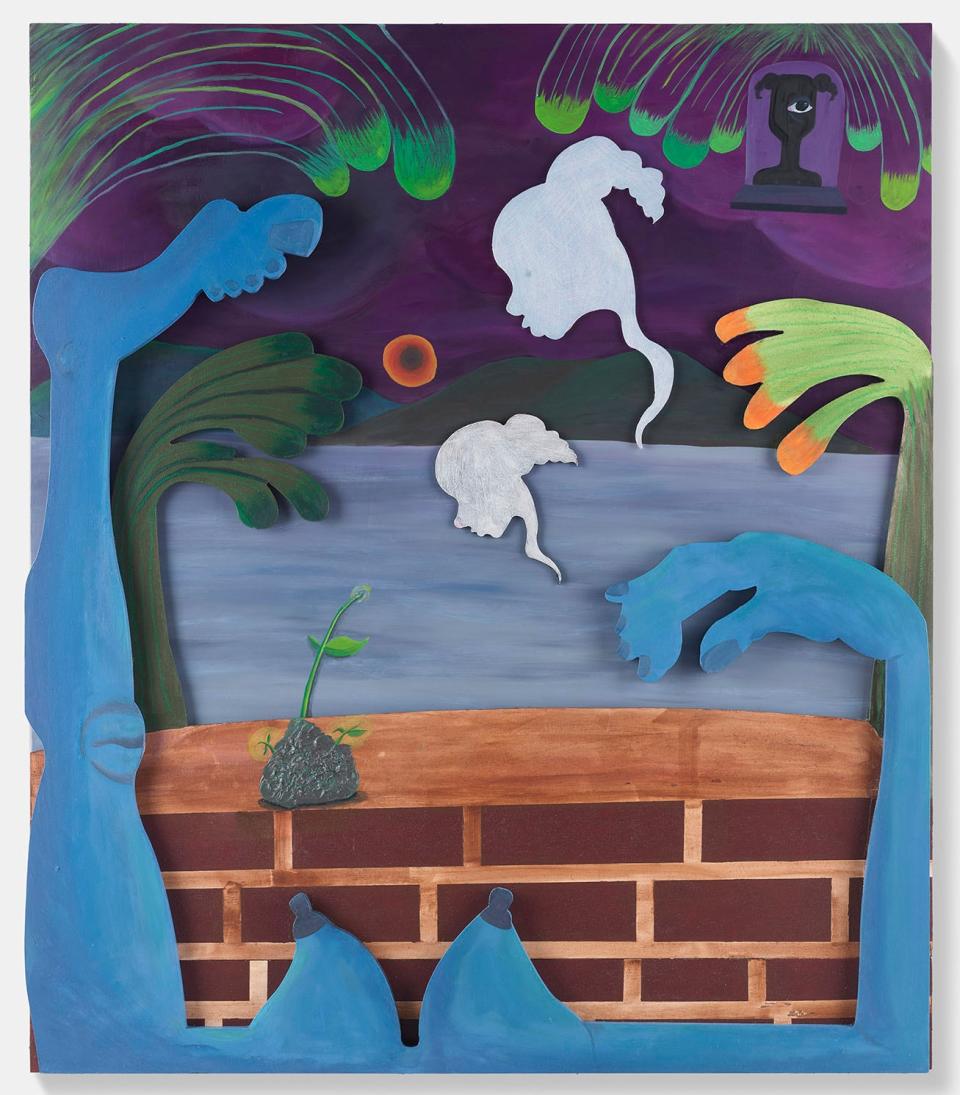

Alexandria Smith, a NXTHVN alumna who now leads the M.A. program in painting at London’s Royal College of Art, describes her practice as a constant re-evaluation of selfhood through a panoply of genderless humanoid figures. “They’re like physical manifestations of the various experiences that people face as they’re trying to understand and develop their identities,” she explains. Her contribution to “Social Works,” Iterations of a galaxy beyond the pedestal (2021), is a work of assemblage named after a poem by her friend and sometimes-collaborator t’ai freedom ford. In it, blue limbs and breasts and the spectral silhouettes of two disembodied heads frame a dusky seascape, mounted above a grid of wooden panels. At a glance, the effect is almost theatrical; like a staging of Black life in all its (surrealist, fragmentary) forms. “Alexandria is showing a painting where she’s thinking about her own world-building, and [asking], Okay, if I could step outside the realities of this moment, what sort of world is possible?” Sargent says. “There’s sort of an Afrofuturistic aspect in some of the logic of the artwork on display.”

For Smith, it’s a thrill to be included in the show. “I studied some of these artists when I was in grad school.” she says. “Some of them were my first introductions to what the possibilities were for being a Black artist—that you didn’t have to be this one type of artist making this one type of work; that we could be expansive, complicated, and not monolithic in our approach.”

Christie Neptune, another former NXTHVN Fellow, uses photography, film, and sculpture to consider how race, class, and gender all converge within her “internalized experiences.” “I look at the body of work as a way to explore how I personally navigate this space as a Black female living on the margins,” Neptune says. For Constructs and Context Relativity — Performance II (2021), her three-channel video installation in “Social Works,” Neptune trained her attention both on her immediate surroundings, in the New Haven neighborhood of Dixwell, and on certain psychological structures. The work has “a lot of internal reflections, asking, How do you know you exist? or, What is Blackness? How do you define these things?” Neptune notes. “It reflected a great deal of what I was reading this time: I was looking a lot at Descartes’s Meditations, I was very interested in Nick Bostrom’s simulations, and then tying those two things into Blackness and these socio-political systems that govern our modes of perception and don’t really have a sense of physicality to them, but are very real and have very real impacts.”

Like Smith, Neptune doesn’t take her placement in the Gagosian show for granted. “Being a part of this is definitely a humbling experience. It is a reflection of all of the efforts of artists who have come before me, and who have worked so diligently to open the doors and pave the path for younger artists like myself to have a chance to be seen within this field,” the says. In its way, the experience is “very surreal, out-of-body, otherworldly—very sci-fi. It’s Blackness of the future, Blackness progressing, Blackness defying these myths and limitations and asserting itself.”

There is, of course, another side to Sargent’s directorship, too: the business of actually selling art. Yet even in that area, Sargent is committed to empowering the Black community. “When I took on this job, I wanted to engage all aspects of it. I wanted to think about what it means to place works inside museum collections; to make museums more reflective of the communities and societies in which they are,” he says. “I was also thinking about doing exhibitions and thinking about younger collectors—particularly younger collectors of color—and how to get them engaged and get them access to works.”

It’s one thing to stage a show like “Social Works,” he adds, and “quite another to be a shepherd of where that work is placed, and make sure that that placement continues a cultural engagement.”

Still, that process begins with allowing a wide cross-section of artists to articulate their distinct visions—something that the new show most certainly does. “It’s not just focusing on one type of engagement; I think you get engagement from all these spaces because the realities have changed across generations,” Sargent says. “I wanted to make sure that all of those realities and all of those perspectives were represented. And thank God we have a big gallery on 24th Street.”

“Social Works” is up at Gagosian’s 555 West 24th Street gallery through August 13.

Originally Appeared on Vogue