'Smoothness' in parts of brain's surface may boost risk of depression, study suggests

Having a smoother brain surface could reveal your likelihood of developing major depressive disorder (MDD), according to a new study.

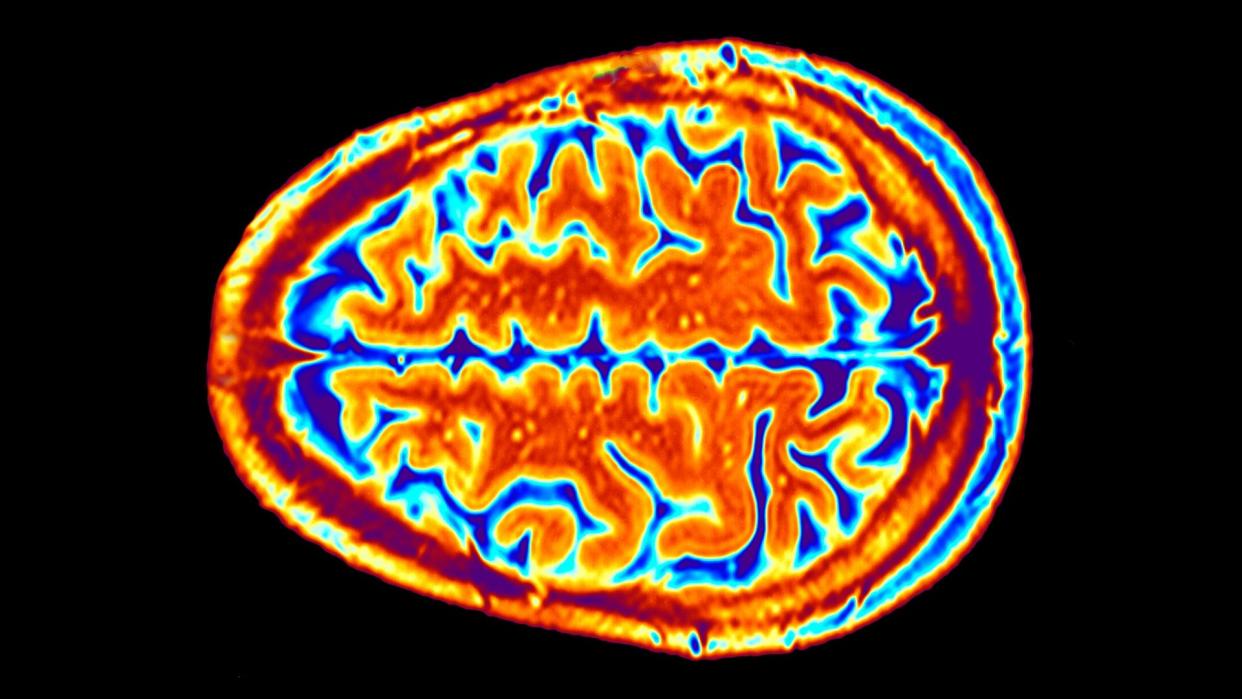

The outer layer of the brain, called the cerebral cortex, is folded into distinct patterns known as gyri. The process by which these wrinkles and grooves form — gyrification — typically begins during the second trimester of pregnancy and continues after birth.

Previous research has provided insights into a possible link between low gyrification and MDD. However, a reliable biomarker, or measurable feature of the brain that could help detect who may be likely to develop the disorder, has yet to be identified.

The answer may lie in looking at the ratio of curved to smooth surfaces of the cortex, using a measurement called the Local Gyrification Index (LGI), the researchers behind the new study propose.

Related: Australia clears legal use of MDMA and psilocybin to treat PTSD and depression

By analyzing more than 400 brain scans from individuals with MDD and comparing them to scans from people without the condition, the scientists found that the former individuals have comparatively fewer folds in several key regions of the cortex, meaning those portions of the cortex look "smoother."

The authors say the findings, published in May in the journal Psychological Medicine, may have important implications for earlier detection of MDD, which affects 3.8% of people worldwide.

The "first-of-its-kind study" both investigated the potential link between depression and differences in LGI across the cortex and looked at whether LGI could be tied to specific symptoms of depression, study author Byung Joo Ham, a professor of psychiatry at Korea University College of Medicine, said in a statement.

The team measured the degree of folding in 66 regions of the cortex using LGI. A higher LGI corresponds to a surface that is more folded, and vice-versa.

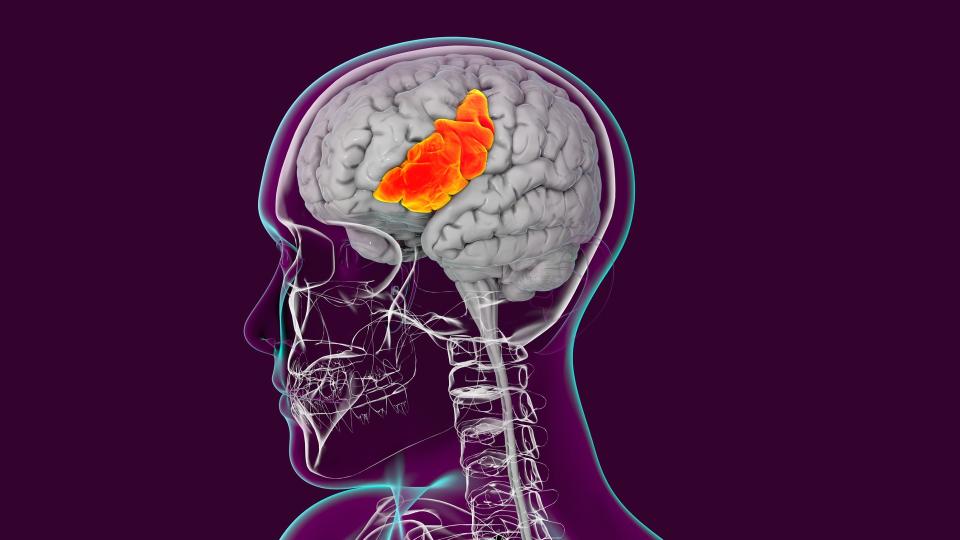

People with MDD had a reduced LGI than those without the disorder in seven cortical regions including those known as the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and insula, as well as certain parietal and temporal regions. These areas are involved in a wide variety of processes such as cognition, emotional regulation, sensory processing and memory formation. Structural differences in these regions have been linked to depression in earlier studies.

The biggest reduction in folding, however, was seen in the left pars triangularis, which is located in the so-called Broca area of the brain, which is critical for the production of speech and language.

So why might smoother brain surfaces be linked to MDD?

"The cortical regions that we assessed in our study have been previously shown to affect emotional regulation," Dr. Kyu-Man Han, an associate professor of psychiatry at KUCM, said in a statement. "This means that abnormal cortical folding patterns may be associated with the dysfunction of neural circuits involved in emotional regulation, thus contributing to the pathophysiology of MDD."

Related stories

—'Magic mushroom' compound creates a hyper-connected brain to treat depression

—A 'pacemaker' for brain activity helped woman emerge from severe depression

—Psychedelics may treat depression by invading brain cells

In the paper, the authors highlight that future research will be needed to investigate the specific genetic and environmental factors that may influence cortical folding during early development and subsequently predispose someone to developing MDD later in life.

They hope, however, that the identification of a measurable biomarker in specific regions of the brain could one day be used to help finetune targeted therapies for depression.

"Our findings can provide a basis for the selection of targets for future neuromodulation treatments [therapies that tune the activity of the brain] including non-invasive brain stimulation with electricity, especially in the prefrontal cortex, to improve the symptoms of MDD," Ham added.