A Slice of Family History

Several months ago, I received an unexpected UPS delivery: a cardboard box from my wife Liz's Aunt Mary in Omaha, Nebraska. Inside, buried among the packing peanuts, I found an old black leather knife roll—a huge one—heavily worn and without a note. But I knew instantly what it was: the knives of my wife's grandfather, Mary's father. And I wondered if it might not carry a message from the past, if only I could figure out what.

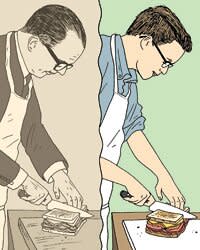

I never met my wife's grandfather. He died relatively young, back when she was in second grade. But when I first met Liz, a picture of the man chopping vegetables hung in her kitchen, as well as in the kitchens of all her food-besotted cousins. "Papa"—his name was Bernard Schimmel—loomed like Moses in that family; over time, I grew more and more curious about him. A professional chef who had trained at the world's oldest and finest hotel school, in Lausanne, Switzerland, Bernie seems to have had an outsize, gregarious personality, a natural party host who loved his Scotch, his lemon drops and his three daughters, one of whom was Liz's mother, Judy.

Bernie was also the head chef and dining consultant for the hotels that his own father had built along the rail lines south of Chicago in the mid-20th century. At one of those hotels, Omaha's Blackstone, family lore has it that Bernie invented the Reuben sandwich for one of his father's regular poker buddies, Reuben Kulakofsky. (A competing origin story credits an earlier "Reuben Special," from a New York deli, but that sandwich had neither sauerkraut nor pastrami and was not grilled.)

I'm something of a knife geek, so my first hope, as I opened Bernie's knife roll, was that I would find treasures—maybe a collection of midcentury carbon-steel Sabatiers, from Bernie's time in Switzerland. Instead, I found run-of-the-mill American stuff: stainless steel slicers for bread and big roasts; a lightweight boning knife for lamb and poultry; a long fish-filleting knife; and a bunch of accessories, like a melon baller, a butter curler, an orange peeler, an oyster-shucking knife, old salad tongs, a carving fork and a plain wooden spoon. What I found, in other words, was the functional tool kit, heavily used but well maintained, of a working Midwestern hotel chef from the 1950s.

Tools are for using, even heirloom tools, but I felt a little stumped: If I dumped all of Bernie's things into my own kitchen drawers, the collection would get lost among my many implements, fast losing their identity. If I left them all in the knife roll, they would stay there forever, unused and under-appreciated.

All this mattered to me because I never cooked before I met Liz. In fact, I never thought much about food. But after we got engaged, Liz's parents started taking us along on their competitive restaurant-going, hitting every great San Francisco spot: Zuni Café, Gary Danko, Spruce, Charles Nob Hill, Aqua. In their company and on their dime, I ate my first foie gras torchon, my first fresh truffles.

I knew I would never be able to afford regular Michelin-starred fabulosity on my own, so I taught myself to cook. By the time Liz and I had two daughters, cooking had become my primary pastime. I blew the first few meals I made for Liz's parents—some through poor menu selection, like serving a main course of pig's liver caillettes (sausage patties made from liver and spices), wrapped in lacy caul fat and baked. Other meals flopped through my sheer ineptitude, like the time I opened the oven, with dinner already an hour late, to find my chickens raw and cold. But I fought my way toward triumph, culminating in a nine-course menu from The French Laundry Cookbook, prepared with help from my then-seven-year-old daughter Hannah, a cheerful and brilliant assistant.

After that, Judy began to say that "Dad" would have loved knowing me, that he would've loved my fascination with the craft of cooking. I felt flattered by this, and I suspected that I would have loved knowing Bernie, too—not just the chance to learn from him, but also the chance to eat, drink and party with a man whose appetites apparently matched my own. The gift of the knives, I thought, might reflect nothing more complicated than that. They were just knives—less fancy and less materially thrilling, to be honest, than all the handmade Japanese blades I'd accumulated on my own. The talismanic power of all this stuff, if it had any, came from its integrity as a collection, and the link that it provided to Bernie himself.

For this reason, I felt grateful when Judy asked me one day to bring the knife roll to a family reunion. She was going to serve Reuben sandwiches at a picnic dinner, and she thought it would be fun to let her cousins cut those sandwiches with Bernie's big slicers. So I did, handing them over before the meal and receiving them back again afterwards. On the way home, in the car, liking how the day had felt, I thought perhaps this was the answer: As Guardian of the Knives, I would store the collection in my home as a complete entity, but I would bring it out for key family functions.

My daughter Hannah, wise beyond her years, found this ridiculous: "Daddy!" she said, exasperated. "Stuff is supposed to be used. You're not supposed to just hide it somewhere!"

I did not own a 12-inch chef's knife, so I figured I would add that one first to my regular rotation, if only for slicing big piles of leafy greens into chiffonades. Pulling that hefty knife from the roll, I noticed a few fine, bright scratches near its blade edge, as if it had been sharpened only days earlier. This caught my eye because the knife had not been touched at the luncheon. So I scraped the blade softly sideways across my forearm, a standard sharpness test: Arm hairs flicked free, effortlessly, one after another. The blade was an absolute razor, so finely honed it wouldn't have stayed that way through more than a few days' cooking.

I phoned Judy first, assuming she had paid to have the knives sharpened after her father passed away. Judy had no idea what I was talking about. So I called Mary, who laughed out loud. "Dad must have left them like that," she said, chuckling. "I haven't touched those knives since he died."

And that's how it happened—that's how I felt Bernie reaching through time, making contact with me. Every chef drags a fingertip sideways across the blade edges of his knives, testing their sharpness; Bernie's own fingers, therefore, had felt precisely the edge I was feeling.

Hannah, by this point, was poring over the contents of the knife roll, marveling at all these little tools from her great-grandfather, the legendary cook. "And what's this thing?" she asked me.

She held a battered old steel tasting spoon. It was stamped, on its face, with the names of the Schimmel hotels in curiously tiny lettering: Omaha's Blackstone, of course; but also the Cornhusker in Lincoln, Nebraska; and the Lassen in Wichita, Kansas; and the Custer in Galesburg, Illinois. Not one of these hotels remained in business, and yet this spoon had served in Bernie's most personal, intuitive act: tasting. Holding it in my hands, thinking of all the times I'd brought a sauce to my own lips, I felt a link to Bernie, and to the simple love of food he had passed along to his daughters. And, through them, to me.

Daniel Duane's F&W piece about learning to be an intuitive cook was nominated for a James Beard Foundation Award. His memoir, How To Cook Like A Man, will be out in May.

Kitchen Tools and Design: