Slavery, Rijksmuseum, review: a brave reckoning with history – if far behind Britain

Hanging from the ceiling at the Rijksmuseum, like a beautiful chandelier, are hundreds of sparkling blue glass beads. They’re thought to have been used as currency by people enslaved by the Dutch on the Caribbean island of Sint Eustatius. Local legend has it that the beads were thrown into the sea when, after a series of mass escapes, the slaves won their freedom. Today, when those same beads re-emerge from the waves, some see them as precious trophies.

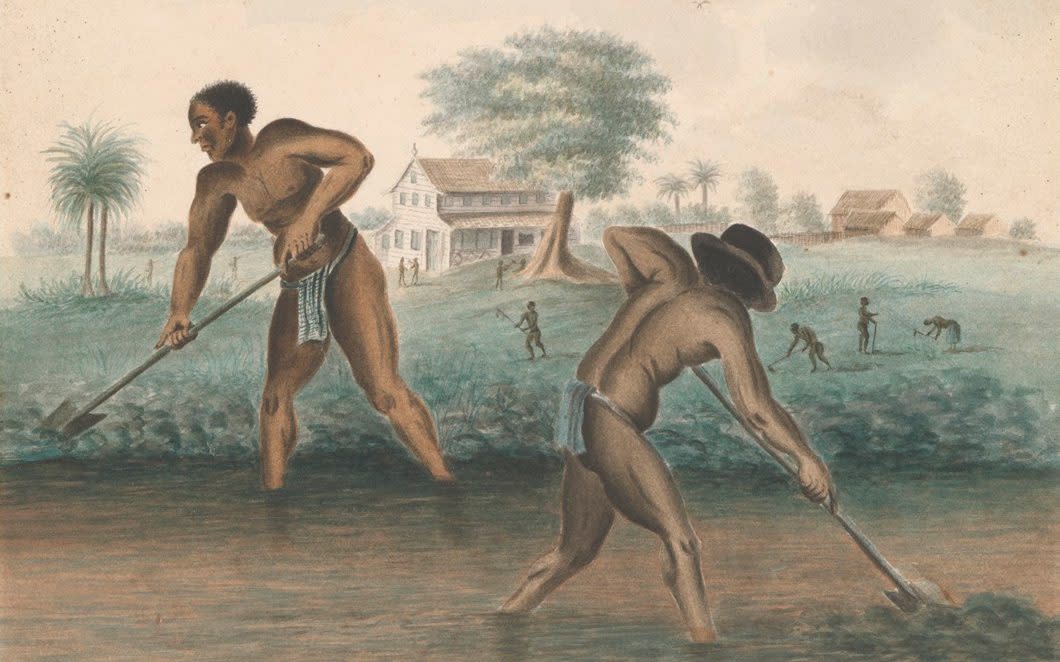

This deep-blue painted room is part of Slavery, an extraordinary new exhibition launched this week at the Rijksmuseum, which delves for the first time into this aspect of Dutch history. Through artefacts, church records, letters, paintings, maps, oral history and songs, it tells the stories of 10 people whose lives were involved in slavery – as slave holders, enslaved people and freedom fighters.

The blue room, for instance, is a testament to a woman called Lohkay, who had a breast amputated as punishment for trying to flee. Her story is said to have inspired mass escapes in Sint Maarten, Sint Eustatius and Saba in the Dutch Caribbean; these were known as marronages, and they led to plantation owners petitioning the Dutch government for an end to slavery, long before it was outlawed in 1863. (They didn’t have a moral objection; they wanted government compensation for the loss of their labour force.)

In a series of vividly-painted rooms, the exhibition also tells the stories of João, Wally, Oopjen, Paulus, Van Bengalen, Surapati, Sapali, Tula and Dirk. Some are familiar from works of art – the wealthy Amsterdammer Oopjen Coppit is pictured in wedding portraits by Rembrandt – while others come from tales pieced together from Brazil, Suriname, the Caribbean, South Africa and Asia.

It's a tall order, digging up this level of detail, because the history of the Dutch “Golden Age” was written by the powerful: enslaved people typically only appear in lists of possessions or ships’ cargo, criminal judgements, and at the corners of paintings. So the Rijksmuseum has also used oral histories, songs and traditions, treating these sources as equally reliable as church records and legal documents. Although the Rijksmuseum makes a compelling case that it is telling these people’s “true” stories, in some senses they are metaphorical, because we can never know. Nevertheless, the exhibition is surprisingly convincing throughout, because the curators don’t overstate their factual knowledge. Instead, a set of stocks, a branding iron, or the sounds of a song of protest punch home the realities of slavery.

Slavery opens to Dutch schools this week, and will open to the public when coronavirus rules are relaxed. It has proved a complex, four-year project for a team including the Rijksmuseum’s head of history, Valika Smeulders. “We want people to understand the bigger system,” she says, “but also place themselves in the shoes of people who lived there.” At the start of the show, the multi-media installation La Bouche du Roi (1997–2005), by Beninese artist Romuald Hazoumè, involves a “slave ship” of 304 pungent old petrol cans, representing the millions of people trafficked from the west African coast. Later, at the end of the exhibition, visitors are invited to stitch, write or model something for the Curaçaoan artists David Bade and Tirzo Martha’s ongoing artwork, Look At Me Now, to reflect on status symbols, freedom and our geographical origins.

Some of this might sound trite, but given that the museum is addressing a local audience in which some people still celebrate St Nicholas’s feast by wearing curly wigs and “blacking up” as his attendant Zwarte Piet (Black Pete), even small actions might open a conversation about the reverberations of slavery in the modern-day Netherlands. The country has a complicated relationship with its past: the Mauritshuis museum has removed a bust of its founder, plantation owner Johan Maurits, from its lobby, while Amsterdam is renaming streets after anti-slavery campaigners – but a national apology is considered too polarising by caretaker prime minister Mark Rutte.

The conversation in the Netherlands is some years behind the one in Britain. Last year, the UN’s rapporteur on racism didn’t pull her punches in telling the Dutch that systematic racism exists, and they are nowhere near as tolerant as they like to think. In London, by contrast, this kind of exhibition could be even bolder without alienating some of its audience. “There’s not a week that goes by without [slavery] being in the papers,” Smeulders adds. “People look at this past from very different angles… and in the conversation, they don’t find each other.”

The tales in Slavery, whether you see them as “true stories” or metaphors for forgotten millions, are overwhelming. They range from the story of Sapali, considered a mother of the escaped community of Maroons in Suriname, who, tradition has it, hid rice grains in her hair in order to smuggle food to survive, to Paulus Maurus, a black servant in the Netherlands, who became a timpanist with William III’s mounted bodyguard.

But the last room of the exhibition, the quietest, is the most striking. It’s painted yellow, with low stools and a wall of mirrors. If the show is trying to make even the most reluctant visitor acknowledge an appalling history and think about what it means to them today, it works: whether you feel shame, horror, kinship, or not, it’s impossible to ignore the realities of slavery – as, for years, the Rijksmuseum did, even though it was built upon its wealth.

When you sit on one of those stools, you see reflected both international words for freedom and equality – such as Curaçao’s “libertat galité” – and yourself. The Dutch “Golden Age” doesn’t glitter as much in this light.

Closed until further notice to the public (bar students), but available online. Info: rijksmuseum.nl