Size 8 is 'fat' in France, says plus-size author of her country's secret weight obsession

It is a truth, pretty much universally acknowledged, that French women can not only have, but also eat their cake — and their croissants, cheese, and charcuterie — without gaining an ounce.

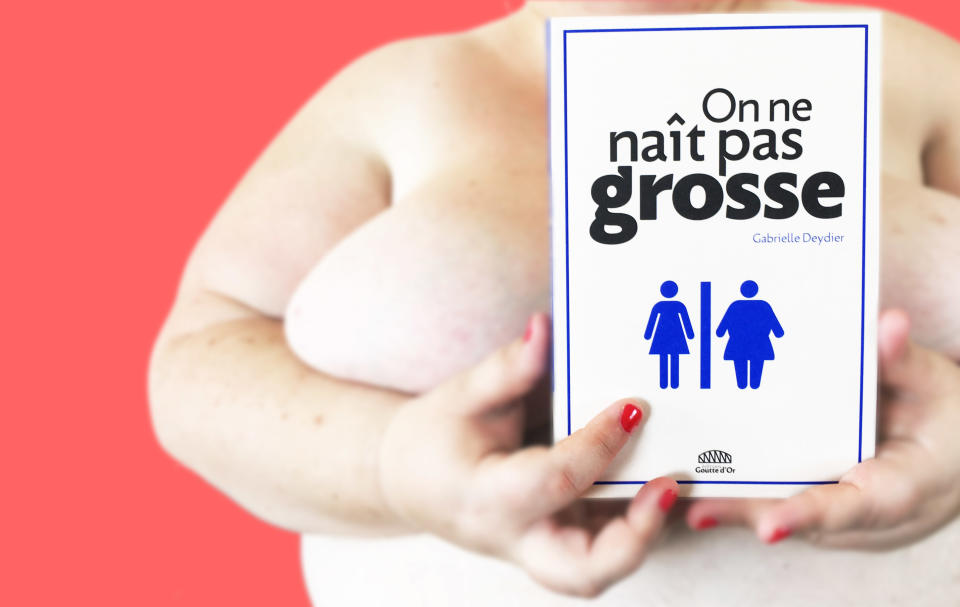

Right? Well it was, at any rate, until the middle of June, when the new book We’re Not Born Fat (On ne naît pas grosse), by Gabrielle Deydier, shed light on France’s and French women’s attitudes toward food, weight, and body image.

The book has shattered the romantic ideal of the French woman, one that’s been extolled over the years in books and magazine articles, as naturally and effortlessly slim. Because according to Deydier’s research, French women are obsessed about their weight, and in a country where “you’re considered fat if you’re a size 8,” many are prepared to do what it takes to stay well below that number, including extreme dieting, chain smoking, and resorting to bariatric and cosmetic surgery.

“There’s this idea that there are no fat people in France, Well, it’s just that you don’t see them because they hide themselves away,” Deydier tells Yahoo Lifestyle. “In France, people don’t mince words — they tell you what they think about you, and through my whole life, I have faced insults and discrimination.”

We’re Not Born Fat, Deydier says, came out of a chance encounter in July 2016 with Clara Tellier Savary, from the newly formed publishing house Editions Goutte d’Or, and it is as much an exposé of France’s attitudes toward weight as it is a chronicle of Deydier’s own experiences as a plus-size French woman. And with the book, France seems to have let out its collective waistband.

Deydier has received scores of letters from readers. Many thank her for enlightening them on the harshness overweight people endure in France, and apologize for the way in which they may have discriminated against plus-size people.

“I also get letters from women thanking me for telling it as it is, for liberating them from their complexes,” Deydier says. “One woman wrote that she has been making herself throw up for 20 years to stay thin so she could keep her husband and her job.”

The book is such a hit that Deydier received a call from the office of the mayor of Paris, inviting her to be a key participant in France’s very first anti-fatphobia day, or Journee contre la Grossophobie, which is being planned for December.

More importantly, We’re Not Born Fat has reignited France’s fat-positive movement.

“We’re so happy to see the impact that Gabrielle’s book has had in France — to see how ignorant people were about the many discriminations we face here and to see how other fat people have been able to come forward, thanks to her experiences,” Daria Marx, founder of Gras Politique, an organization that advocates for France’s overweight population and collects testimonies about discrimination, tells Yahoo Lifestyle.

“Before this book, the term ‘fatphobic’ didn’t exist in France’s vocabulary. But now people can recognize what discrimination against fat people is. The book is just the beginning, though, and we at Gras Politique will be organizing a series of events to continue to sensitize people to the issue of fatphobia, and to advocate so that fat French women can have the same rights as those that wear a size small.”

Deydier, who weighs 330 pounds, says she began gaining weight in adolescence. In addition to facing constant scrutiny and ridicule, she struggled to find clothes to wear and apartments to live in. And although she has degrees in film/media studies and political science, she struggled to find a job.

“People tell you they’re not going to hire you because you’re fat,” she says. “There are so many obstacles you face here if you’re fat: There are no plus-size hospital robes, for instance. And you’d be hard pressed to find a wheelchair that can accommodate an overweight person, so if you’re injured and you have to go to hospital, you’ll probably have to walk down the hallways.”

In France, it’s a cultural imperative for women to be able to cook fine meals with premier ingredients, to throw fabulous parties and entertain guests, but they’re also supposed to stay thin their whole lives, Marx says, to live up to an ideal vision of how a woman should be. Women bear the brunt of this “double whammy” of sexist and weight oppression, and overweight women are so harshly stigmatized that they tend to hide themselves from society.

Now Marx is hoping that the book will urge France’s overweight population — women and men alike — to come out of the shadows, find their voice, and claim access to public space.

Gras Politique, co-founded by feminists and fat-positive activists Marx and Eva QueenMafalda, is a known voice in France’s fat-positive movement, but although this movement began in the mid-1980s, it has lacked firepower and failed to become mainstream.

In the U.S., fat activism dates back to the 1960s, pioneered by groups like the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance, but the movement only became visible to the mainstream world with the advent of social media, says writer and activist Virgie Tovar.

“The self-documentation made possible with phone cameras was revolutionary because typically fat people are documented in an ethnographic way, by other people for other people,” Tovar says. “This was the first time that large numbers of fat people had access to both camera technology and a means to publish photos of ourselves for free.”

But despite the conversation being mainstream, Tovar still feels we have a long way to go with our attitudes toward and acceptance of fat.

“I know I, and many others, still fear fat hatred every time we leave our house,” Tovar says. “Fat people are still an open target for many who feel they have the right to be bigots without fear of repercussions. Fat bodies, like women’s bodies, are still considered part of the public domain and not deserving of privacy or dignity, and people feel a lot of righteousness when it comes to issues they feel fall under the domain of health.”

There is a huge gap between the vibrancy of fat activism in the social media sphere and what happens in the real world, agrees Instagram sensation Jessamyn Stanley, a yoga teacher and author or “Every Body Yoga.”

“I face constant pressure in my life to change the way I look from every outlet — my family, my friends, strangers,” Stanley says. “Unfortunately, we live in a society of assimilation where there’s a deep obsession with everyone looking the same. If you don’t, you’re still swimming against the tide and even if you see fashion designers being more inclusive, they’re still, in my view, promoting a very specific idea of beauty that does not represent all plus-size women.”

Unfortunately, the discourse around fat is still centered on the notion of weight loss, Tovar says, and this wrenches valuable resources and attention away from a very important movement.

“Fat liberation is nuanced, new, interesting,” Tovar says, “and I don’t understand why some women can’t respect that people want just one space — the fat movement — where they don’t have to hear about weight loss.”

This is Deydier’s ideal as well, and she hopes that her book will enable the plus-size community in France to take the first important step in that direction.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Black women converged on the National Mall in peaceful protest

People are demanding that Amazon remove this ‘anorexia’ sweatshirt

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.