Six Centuries Later, The Decameron Is Suddenly the Book of the Moment

All of a sudden, everyone seems to be reading Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a novel published more than 600 years ago.

Virtual books clubs are analyzing the 1353 masterpiece, consisting of a hundred stories told by three young men and seven women during their quarantine in a villa outside Florence. The critic Eric Banks has been running a five-week, $150-per-person Zoom reading group in conjunction with McNally Jackson Books. The classicist Daniel Mendelsohn tweets a new passage from it every day. And it even prompted a key plot line in Richard Nelson’s latest play, What Do We Need to Talk About?, when one of the characters suggest they imitate the Florentines and tell timeless stories about the human condition to make them forget, perhaps for just an evening, the plague outside their doors.

Oddly, given my lust for fiction, I had never read The Decameron, probably because I didn’t major in English, where it no doubt would have been forced upon me. Maybe now was the time to try it. It would certainly be more challenging than binge-watching TV shows I had missed and more satisfying than the Zoom cocktail parties that I’ve started avoiding, just as I did in real life, a term now poignant and expanded in meaning.

In the novel, the young Florentines head to a villa two miles outside the city, which, apparently in those days, was far enough away to feel safe from the Black Death. (Like Americans now, they seemed to think that a few weeks in quarantine was enough, unlikely given that half the population of Florence ultimately perished.) Like today’s pandemic, it had started in China and worked its way around the world through trade and war, carried by fleas that jumped from rodents to humans.

Unlike most of us who are sheltering in place, the Florentines in The Decameron arrive with their servants and settled into an elegant house furnished with fine sheets and bouquets of flowers. That meant they had no need to figure out how to divide up chores, the likely stress point in many households now.

On their first day, one of the seven women, Pampinea, takes the lead, arguing that they needed structure for each day, and insisting that compliance would be enhanced if there was a king or queen each day who made decisions. By alternating power, no one would feel left out.

As the unanimously elected queen for the first day, she suggests each person tell a story each day for 10 days—hence the 100 stories of The Decameron, which, from the Greek, means 10 days. When not telling stories, they would nap, walk, sing, and eat fabulous food. If we are not sick and not impoverished (two big ifs these days), the book is a guide to setting up routines and structuring our lives.

Last week, to gain better insight into the book, I joined 78 other people for a Facebook Live presentation sponsored by The National Humanities Center. Jane O. Newman, professor of comparative literature at the University of California at Irvine, provided the historical context for the book, and after her talk, took questions from the other participants. She described the stories as allegories of the virtues, with the women representing qualities like prudence, justice, and fortitude, and the men representing anger, lust, and reason. “His stories teem with a kind of diverse humanity,” Newman told us.

In a set of slides, she showed pictures of cool things like the protective gear doctors wore in the 17th century, with masks that made them look like they had dressed up as birds. Although the plague killed as much as 60% of Europe’s population, she saw some upsides: It led to reforestation, because there weren’t enough peasants to farm the fields. And the ones who remained had more power, and could demand higher wages.

(If you want to know more about The Decameron, you can watch her talk, here, and if you really get hooked, go to this Brown University site.)

The stories delve into the full range of human behavior, from magnificent to despicable. As Newman put it, Boccaccio’s stories remind us of “our basic (and sometimes base) human qualities and the not-always pretty sides of our humanity that cannot be avoided even when allegories and artifice prevail.”

And, indeed, the first story introduces a character who reminds me of someone with orange hair who happens to lead a country that was once a beacon for freedom and intelligence. Ciappelletto is a thoroughly amoral man who would give false testimony, draw up fake documents, stir up enmity among his friends, and happily witness murders and other criminal acts. Dying from the plague and needing confession to send him on his way, he manages to convince a holy man that his life had been one long series of selfless deeds. He not only wins over the priest and obtains absolution, he ultimately is hailed as a saint. He gets away with everything, and still gets beatified.

In the 1300s, those who were sheltering in place didn’t have the news or Twitter to remind them each day of the pain and suffering around them, but even in a villa, there is no escaping human nature. One of the 10 storytellers, Dioneo, never wants to follow the rules and always insists he tell his story last. The less attractive qualities of our human character can never be escaped.

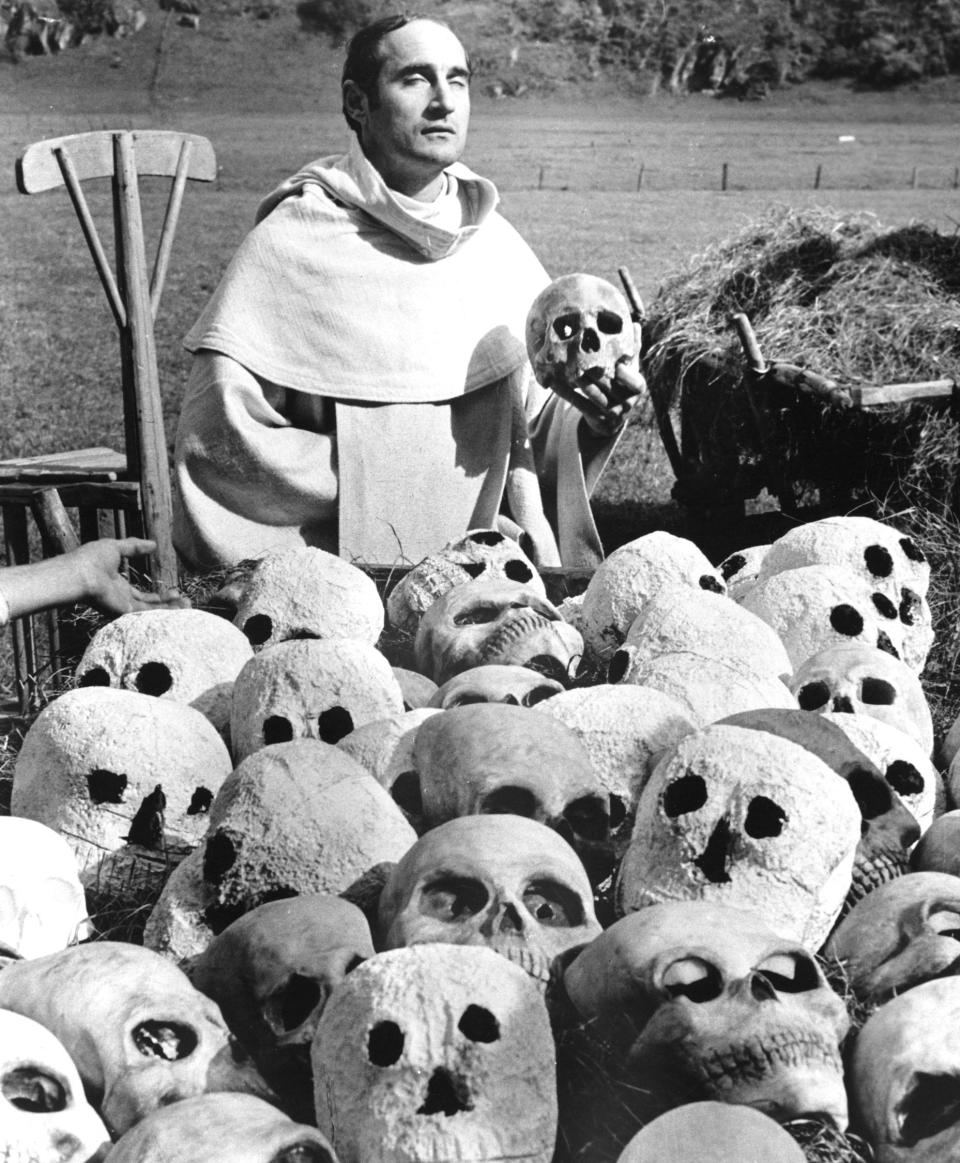

THE DECAMERON, 1971

The concepts of The Decameron came into my life just in time, because recently, I started to feel oppressed by my role in ordering food for our quarantine household of four enthusiastic eaters. The constant need to decide—so different from our former lives back in the city, when at 5 p.m. I could announce, “I think I want to make chickpeas,” and walk half a block to get the necessary ingredients. Now, in quarantine, planning is key, or else how would I know when I was ordering food whether it would turn into meals that our group wanted to eat? Inevitably, after I placed an order, someone would say, hopefully, “Did you get strawberries? Or bologna?” to be met with an angry stare from me.

I’ve been wanting to lose some of the burden of decision-making, and inspired by the young Florentines, I’m thinking we have to try something along the king/queen model. Because our concerns are more practical than theirs, our ruler might have to be in charge for a week. Perhaps that will lead to power-mad actions, or more conflict. We’ll see.

I also felt emboldened by the life of the Florentines to enjoy the weather, the light, the chance to walk and putter and smell the spring flowers. What good is guilt, or denying ourselves beauty where we can find it?

The other day, I heard about the daughter of a friend, a college student, who planned to go off with a bunch of friends and quarantine together. Makes sense. I don’t know if they got their inspiration from The Decameron, but in any case, it provides a roadmap for getting through this if you’re not sick: share stories. And always pick a king or queen.

Originally Appeared on Vogue