My Sister, the Runner?

AUGUST 2014

I’m worried about my little sister. Barely half a mile into her first 5K, and she’s gasping. Her face is pinched. Her mouth is twisted in a way that usually portends cursing, a hissing string of “Jesus Christs” and/or a lengthy, jaw-clenching period of silence that I always suspect is directed at me, because it usually is. Now, though, she needs my help.

“You’re doing great, Annerino!” I say. We’re plodding over flat, dusty ground, along the ridge of the Second Mesa, just outside the Hopi village of Shungopavi, the oldest village on the middle of three mesas that constitute the Hopi reservation in Arizona’s northeastern desert. She wheezes, won’t even acknowledge me by turning her head. I wave at the gossamer clouds, at the soft shadows gliding across the brown and white and green and red earth stretching below us, at the loping clots of Native Americans, ahead and behind—mostly ahead—of us. Isn’t this fantastic? Has she ever seen anything so beautiful? Ann grunts.

For the past three months, I had told her—in person, over the phone, through email—about pace, and she had ignored me. I had spoken at length about leaning forward, and core strength, and the importance of visualization, and she had muttered “Jesus Christ!” and ordered me to go watch television, or take a nap, “because that’s what you do.” At the starting line, in the gentle light of a chilly pastel sunrise that would soon shed its seductive costume and turn to pitiless desert heat, I had hummed the Rocky theme song for motivation and because it’s something I often did when I was feeling cheerful, or anxious, and she had commanded me to stop making noise and to leave her alone.

How could I? She has had trouble breathing since she was a teenager. When she was 19, the summer after her freshman year in college, she returned from California and landed in a room at Barnes Hospital (now Barnes-Jewish Hospital) in St. Louis, where we grew up. I was 25 then, soon to be fired from my first newspaper job in Columbia, Missouri, recently broken up with my girlfriend, trying to figure out what to do with my life, worrying about failure and death, not sleeping well, suffering chronic and vague digestive and skin ailments. But my sister needed me, so I drove home, two hours east. It was a bright, washed out Midwestern July day, but in the hospital room all was cool and fluorescent and beeping. There was Ann, in bed, an IV stuck to a yellowing patch on her ancient-looking wrist, her lips chapped, her cheek bones poking out, the piercing blue eyes that had stunned so many boys into shuffling, stammering helplessness unfocused and cloudy. I could hear her ragged gasping, just beneath some off-key guitar strumming. The strumming was coming from a guy sitting in the chair on the window side of Ann’s bed. He had lank brown hair to his shoulders; a long, thin nose; and gray, hungry eyes that reminded me of a particularly mangy desert fox. He was sitting cross-legged, barefoot, and I noticed the bottoms of his feet were black. Our mother sat on the other side of the bed, looking at the guy with a granite smile and cold marble eyes. “So, dear, what did you say you did for a living? And what brings you to St. Louis? And do your parents know you’ve been hitchhiking? Could we help with bus fare to wherever you need to go?” The doctors suspected pleurisy, or a rare fungal infection, and Ann was in a great deal of pain, and barely had the strength to say “water,” but still she managed to focus and narrow her cloudy eyes upon my mother, who pretended not to notice.

When Ann was released, our mother suggested she move home for a little while and maybe they could go shopping together for some “nice” shoes, “because those cowboy boots you wear all the time must be so uncomfortable.” Ann declined. Five years later, after she had graduated college and had moved to San Francisco and we were both visiting home, I took Ann out for a hot fudge sundae at Ted Drewes Frozen Custard stand and, sitting on the hood of my pale blue Chevy Caprice on Grand Avenue, in an island of light in the midst of the city’s hulking darkness, asked her if she didn’t think graduate school might not be easier than her life in San Francisco’s Mission District, where she had been learning pottery and selling flowers from a wooden cart. A family member (who has requested that I not identify him) suggested to Ann, when they were in line at a grocery store in suburban St. Louis that, “you get a real job, like this young lady” (pointing to the grocery store bagger—“Not the clerk, the friggin’ bagger!” Ann remembers), “rather than trying to make a living throwing a bunch of mud around.”

She needed me then. She needs me now. Of course I can’t leave her alone. “Maybe you can pick up your knees a little, rather than shuffling,” I say. We’re moving at a 13-minute-mile pace. She cuts me a look, continues shuffling. Thirty-three years have passed since the hospital stay (doctors never did figure out what was wrong). Ann is 52 now. I am 58, still single and worried, but my stomach and skin are better. Family resentments have calcified, then softened, and chipped and calcified some more. Were they softening or calcifying here among the Hopi? I wasn’t sure.

“And maybe you could use your arms a little rather than flopping them around.” We had started near the front of about 150 mostly Hopis, with Navajos and maybe Zunis, too, many of them lean, muscled, serious-looking, and after about 20 yards, nearly all had passed us, the chubby and old among them.

“We’re not really part of the community this far back,” I mention to Ann. “I think it might show more respect to the reservation elders if we got closer to the middle of the pack.”

“Go!” Ann said. “Just go!” Maybe she yelled a little.

“No, I’m running with you,” I said. “We’re in this together. I’m your coach.”

“I’m not running, I’m jogging,” Ann hissed. “You run how you want to run. Go run your own race. Leave me alone!”

But how could I?

April 2014

Ann and I share a complicated and occasionally fractious relationship, marked by philosophical differences (she believes in homeopathy and craniosacral therapy, I like double-meatball pizzas and Sylvester Stallone movies), dissimilar appetites for hard labor (she gardens, farms, chops wood, installs drywall, and rewires buildings; I enjoy a nice afternoon nap), and differing views on optimal child-rearing strategies (“You are aware that Isaac won’t go upstairs to his bedroom since you showed him the trailer for Seed of Chucky, right?” she had screamed at me during a late-night phone call 10 years ago, shortly after my nephew had turned 6. “Um,” I had replied. “What is wrong with you?” she had screamed, even louder).

When my sister emailed me in early springtime that she was planning to run in the 41st Annual Louis Tewanima Footrace, she might as well have announced that she was going to forge a career in investment banking, register as a Republican, and move into a McMansion. Slender, shapely, a mesmerizer of men, a great beauty and junior high school cheerleader, Ann had decided when she was 16 that she hated all things that smacked of empty consumerism, oppressive patriarchy, and lemming-like adherence to soul-destroying convention (her words). These things included professional sports, nine-to-five jobs, shaving her legs for the next 15 years, the stock market, much of western medicine, expensive athletic gear of any sort, pet dogs acquired anywhere other than a local pound or rescue center, central air conditioning, and shoes (other than cowboy boots, sandals, and Tibetan prayer slippers). Ann matriculated at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she majored in women’s studies with an emphasis on psychology and fulfilled her physical education requirements with African dance. Now she lives in Durango, Colorado, a quiet, semi-sleepy frontier town when she arrived 10 years ago, and today a preferred destination for serious river-rafters, world-class cyclists, mountain-bikers, long-distance runners, “and just about any rich idiot willing to spend five godzillion dollars for Lycra s--t and to devote their lives to going two seconds faster!”

Ann reads The New Yorker and listens daily to NPR. She possesses a singular and wide-ranging sense of style that one day might involve a bright blue miniskirt and matching bright blue sandals she found at a vintage store and another day showcases red skinny jeans, brown Carhartt work jacket, and black Mao hat. She loves jewelry but eschews makeup. “I’m a minimalist,” she says. “If I put on nail polish, I feel like I’m suffocating.”

While partial to organic ice cream and free-trade gourmet coffee, Ann has also, since she was 3 years old, adored bologna sandwiches, potato chips (the cheaper and greasier the better), frozen pot stickers, and Coca-Cola, and she treats herself to at least one serving of each every week, more if she has encountered a labradoodle or received a dinnertime phone call from a marketing company. When she’s not driving one of her two children to a cross-country meet or acting class or ice-skating lesson or rocket-building workshop, or pulling a tomato or garlic bulb from her garden, or walking or feeding the dogs, or throwing a pot or painting a decorative plate, or seeing a craniosacral client, or otherwise “working herself to the bone,” as our mother laments regularly, Ann relaxes by spooning gobs of raw cookie dough into her mouth and watching episodes of Family Guy from a DVD she has owned for a decade. She does this at midnight as Steve (her husband), and Isaac and Iris (the children), and Sam and Brinks (the dogs) sleep. On Sunday mornings, sipping fancy, freshly brewed coffee in the backyard, reclining on her chair, ignoring her kids’ screaming and the dogs’ excited barking, the ringing telephone and the racket her husband is making sawing something or hammering something or drilling something else, she’ll gaze upward at the thick needles of the Ponderosa pine that shades the house and sigh, then speak dreamily of Johnny Depp. If it’s been a really hard week, there will be a large bowl of potato chips within reach.

“I thought you hated organized sports events,” I emailed her. “I thought you hated organized anything. And I thought you had insisted, for many years, that yoga and African dance gave you all the exercise you needed. Why run now?”

She emailed me:

To overcome fear of hard things.

To beat my inner “I am a loser” demons.

To feel powerful in a new way as my beauty fades.

To prove to my ex-husband that I am not a fat, lazy slob.

To connect to my obsessive, power-hungry son.

To give the big F you to all the Durango crazed athletes… I would do it without spending five godzillion dollars on running s--t.

To connect with something bigger than myself.

To conquer middle-aged oblivion.

To set a good example for my 12-year-old daughter.

Also, I’ve always liked, been drawn to, romanticized Native Americans, so of course the only 5K I would ever consider would be on a Hopi reservation. Also, I think the Hopi culture is very cool and of course Little House was my favorite book series, and I sided with the Indians (but they were not Hopis) anyhow…

“Fantastic!” I had emailed back. “I’ll come out and be your coach.”

I offered because over the past decade, ever since I had to quit basketball because of chronic injuries, running had helped me deal with things like stress, anxiety, weight, and the occasional certainty that doom was just around the corner. I could help teach Ann how running might improve her life.

“I don’t need a coach. I spit on coaches,” she wrote back.

“C’mon, it’ll be fun. And I’ll take the kids to movies and stuff.”

“Whatever, Butterball,” she emailed back. Butterball was my nickname as a toddler. She knows I don’t like it.

JUNE 2014

“I hate this,” Ann says.

“No, you just think you hate it,” I say. “Relax. We can go as slow as you want.”

Two months after I decided I would be Ann’s coach, three months before the event, late afternoon, and we’re barely shuffling along the red rubberized surface of Durango’s Miller Middle School track. We’re at 6,500 feet and I’m breathing hard. Ann is merely scowling. As usual, I’m worried about her. “As slow as I want is walking,” Ann says.

“You can’t go that slow,” I say and when I see her start to make the bad face, I quickly add, “but we’re in no hurry. This isn’t competition.”

I’ve learned over the years that Ann does not respond well to direct orders. “All we’re doing is running and talking, running and talking. Just four and a half more laps to go and we’ll have a mile.”

Ann grunts. “Tracks are stupid,” she says. “Jesus Christ!”

“Want to try some visualization exercises?”

“No, I don’t want to do some visualization exercises! God, who invented tracks? What’s wrong with nature? Why are we running on the track, not a trail?”

“I wanted to see your form on a neutral surface,” I lie. The truth is the middle school is only about 100 yards from Ann’s house and, in addition to being lazy, I’m as averse to new things, travel, adventure, and novelty as my sister is to lipstick and paying money for purebred dogs. The track seems simple, and close, and predictable. I take a great deal of comfort from routine. The one person who has most consistently steered me away from that is my sister.

“What about what I want?” Ann says.

“Well, we agreed that I’m the coach.”

“Well, Coach Butterball, I want to do what I want.”

“Please don’t call me Butterball.”

“We’re going to the friggin’ trail tomorrow,” Ann hisses.

“We’ll see,” I say, sanguine, reasonable, coach-like. “But today we’re going to discuss negative splits. Also, did you download the Rocky theme song like I asked? I want to play it for the kids later, to get them emotionally invested in this great adventure.”

Ann stops, and I shout, “No stopping! No stopping!” She starts shuffling again. “Jesus Christ,” she mutters.

It is my second day in Durango. Earlier I had taken 15-year-old Isaac to a superhero movie. Superhero movies as well as hot fudge sundaes seem to ease the kid’s constant worrying—about high school, about his relatives, about whether he’ll be able to fall asleep, about the science exam next week, about college, about adulthood. He reminds me of me. This concerns me. Before that I had enjoyed morning coffee with 12-year-old Iris. (“She likes it,” my sister said when I asked if it was really a good habit for a 12-year-old to be starting her day with a cup of Joe. “You want to fight with Iris, be my guest.”) Our mother had arrived a few hours ago, and was staying at a rental half a block away. I had listened to Ann on the phone as she explained to our mother that no, she didn’t think Isaac was spending too much time on homework, and no, she did not think she would be visiting Portland soon, and no, she didn’t think Iris was too young to ride the city trolley alone, and no, she did not know if there were Internet connections on the Hopi reservation, and no, she did not want our mother to bring over “some nice delicious rye bread” to Ann’s house. I listened from Ann’s living room couch, where I offered coaching advice, watched television, and napped. Whenever I travel, I take a couple days to acclimate. The altitude here has only made that need more urgent.

When I was on the couch, Ann told me that she had already started training. She had been jogging on a nearby trail for the past two weeks.

“You finally got some running shoes?”

“No, I’ve been jogging in my handmade Italian leather boots.”

“Why, Ann? Why?”

“First, because they’re fancy and well made. And second, because I spit on running shoes! They’re ugly and they’re gross. I hate the way Americans wear them in Europe and everyone can tell they’re Americans. They’re so aesthetically wrong!”

I had sighed.

“But then I tried on some running shoes at the store, and I have to say, they felt pretty good. But still! A hundred dollars for a pair of shoes you wouldn’t even wear that much? That could feed a village in Mozambique for a week!”

Finally, when her husband, Steve (a captain for Durango Fire and Rescue, carpenter, contractor, college-educated, voracious reader, runner, basketball player, father of three grown sons, all-around great guy), suggested that they could afford running shoes and she should go ahead and splurge, she had relented, but not before stating, “You’re not the captain in this house!”

We are on our fifth and final lap now. Ann has not stopped bitching about tracks. I hum the Rocky theme song until Ann tells me to stop. We’re at a 16-minute-mile pace. I tell her that finishing strong will make her feel better. She tells me to shut up. I slow down, let her get ahead of me, then, with 50 yards to go, I begin announcing, in the voice that once upon a time, long ago, when she was little and adoring, used to make her giggle: “The great Soviet champion Svetlana Krushakoff has the American novice Friedman in her sights! The Eastern Bloc champion has been waiting for this very moment, because now the soft, entitled, corrupt Westerner will feel the annihilative power of…”

“Shut up!!” Ann screams, but she doesn’t run any faster.

“…the annihilative power of the indomitable Krushakoff and the lazy Westerner will finally recognize the limits of flaccid, indulgent American power. Krushakoff begins her kick. But what is this? The deluded capitalist is not bending. The indomitable Russian legend—half human, half horse, one hundred percentski woman—kicks harder, and harder still! The Soviet heroine has never kicked so fiercely, but the American will not break! What manner of athlete is this Friedman? Krushakoff cannot be…”

“Goddamit! Jesus Christ!” my sister screams, and stops, dead in the track, with 15 yards to go. “Will you stop?!”

That’s when I know it’s going to be a long summer.

April 2002

“Aieeeeeee!” Iris screams. “Blaieeeee!!!”

Iris has been screaming since she was born. She came early, during thick, blanketing fog and 10-below temps, delivered by a friend of my sister’s, who took instructions from Ann’s then-husband, who received them over the phone from the midwife (who got stuck in the fog).

Iris came out purple, bug-eyed, silent, umbilical cord wrapped around her neck. Ann hemorrhaged, nearly bled to death. An ambulance had taken Ann to the hospital. Iris has been screaming for three months.

“Aieeeeeee!” Iris screams. She is undersized and scrawny. She looks something like E.T., but uglier. Her screams are piercing, large beyond any human comprehension.

Ann rocks her daughter, sings to her, asks her what’s wrong. Mother and daughter sway as one at the kitchen sink in the house Ann and her husband built in Silverton, Colorado, during the summer, when wildflowers bloomed and they thought their marriage might survive and when their only direct experience with babies was Isaac, who had smiled and cooed and hummed for the first 10 months of his life, at which point he started asking odd, baffling questions.

It’s early April, and Isaac is 3 and a half years old, Iris is 3 months, and snow has been falling, thick as ash, for the past five days. The single highway that connects Silverton to places that possess pharmacies and doctors and movie theaters and restaurants that stay open past 7, one of the most avalanche-prone stretches of highway in North America, has been closed for two days. This is springtime in the mountains.

“Aieeeeeee!” Iris screams. “Blaieeeee!”

Ann is alone with the kids, and she has been trying to do dishes for the past hour and a half.

“Mom,” Isaac asks as Ann rocks Iris, sings to her, rocks her some more, as Iris continues to scream, “do all criminals smoke?” My nephew (born in a yurt, midwife made it on time, no complications) is as pensive and deliberate as his sister is volcanic. (In this, he continues an apparently chromosomally linked temperamental trend in my family, where the women over the generations have tended to do things like run in leather boots and pull vegetables from rocky soil and slog through the muddy, cratered fields of Eastern Europe carrying pots and knives and rocking chairs and overstuffed couches on their backs while with their gnarled and calloused and weary fingers they battle wolves and anti-Semites; and where we men have told good jokes and enjoyed nice naps.)

Isaac tends to wrinkle his forehead and stare into the mid-distance. I suspect he thinks far more than is good for him. Since he was 3 weeks old, people have called him The Professor.

“Shh,” Ann says to Isaac, rocking Iris, who miraculously seems to be quieting down. “Not now, Izie. We’ll talk about criminals later.”

Isaac wrinkles his forehead. Just as Iris’s screams turn to soft wailing, The Professor pipes up again.

“Mom. What are the approximate chances a meteor will fall on our house tonight while we’re sleeping?”

At this, Iris screeches with joy.

“Irie thinks meteors are funny,” The Professor says. He seems sure of this.

Ann smiles, a wan, nearly hopeful smile, and then, as Iris’s delight turns to horribly loud heinous rage, or bottomless despair, or crushing fatigue (Ann’s pretty sure it’s not hunger; Iris won’t take the bottle), Ann begins to weep.

After college, in San Francisco, Ann had sold flowers, thrown mud around, and after an organic farmer and a comedian, she dated a filmmaker our family suspected was a methamphetamine addict, broke up, and then, heartsick, piled her bags of clay and her wheel and her vintage dresses and her cowboy boots and Tibetan prayer slippers into the trunk of her grimy, dented 1990 Toyota Corolla, and, after buying a book and circling the top five candidates in a chapter called “Cool Mountain Towns of the West,” landed in Silverton, where she dated a guy who painted surrealistic landscapes of rocks and bones, drove a truck for FedEx, taught art to kids, modeled, dug a pit and taught herself the ancient art of pit-firing pottery, dated an ambulance driver, scraped together enough money to buy a 100-year-old shack into which she, with the help of a few friends, installed drywall, electricity, and plumbing. She dated an investment-banker-turned-graphic-designer-turned-ski-instructor-and-itinerant-rock-climber who was passing through town, and they bore Isaac, and they married, and they built a house together next to the shack, and they bore Iris, and Ann nearly died, and Iris started screaming.

Ann and her husband would separate a year and a half after Iris was born. I have been visiting for three days, and at the moment am sitting on the couch with Isaac, telling him stories about alien abductions and the greatest prison breaks in history. Since getting fired and visiting Ann in the hospital, I had held four jobs, moved to New York City, suffered rashes and stomach problems worse than ever, and spent a lot of time wondering what would become of me. But I was more worried about my sister, so I had flown west. I have spent my time in Silverton singing to Iris, hauling the family’s garbage to the town dump, treating everyone to ice cream, teaching Isaac how to say “Pizza night with Uncle Stevie!” and how to eat whipped cream straight from the container, but mostly quizzing Isaac on who he thinks would win in a death match between a grizzly bear and a rhino, a cheetah and a hyena, a whale shark and an orca. He has asked me more times than I can count, sincerely and unsmiling, man to man, scholar to scholar, natural historian to natural historian, to once more describe exactly how the saltwater crocodile kills its hapless prey by utilizing the fearsome “death spiral.” I had told him of the death spiral when he was barely 2, and he never tires of learning more about it.

We are discussing the respective combat readiness and fighting prowess of wolverines and leopard seals, when we both notice how quiet it is. Iris is asleep. We can hear Ann snuffling.

“Hey, Ann,” I say, “why don’t you take mom up on her offer to get you a dishwasher? I really think it might make things easier around here.”

“My dishes”—which she has made—”need to be hand-washed,” she says, “but thanks for the input.” She says this in a tone that makes me think she’s not really that grateful for the input.

“How about letting me get you some machine-washable dishes, then?” I say. “You know, then you might have some time to just relax a little and...”

“Relax?” she says. “Relax?” Uh-oh.

“You want to help me and the kids, Steve?” she asks. “How about you cook for a few months, and clean, and change Iris’s diapers and shop and sell this f---ing house and do something other than tell stupid killer bear stories and gorge yourself sick on Chubby Hubby and whipped cream!?”

“Grizzly bears aren’t stupid, Mom,” Isaac says. “They’re actually very intelligent. They even know how to kill porcupines by flipping them onto their backs, then scooping out their meaty bellies with their giant claws and…”

I hear my sister start to snarl. Iris is awake. I am really worried about Ann.

“Ann, is there anyone in town you can talk to?” I ask. “Like, you know, a professional? I think making an appointment with someone, and using a dishwasher and letting me get you some washable dishes and silverware…”

Ann says nothing. She has turned her back to Isaac and me. Iris is starting to make noise. Happy noise or sad noise, we will soon discover. Ann’s shoulders seem to be heaving.

“Mom,” The Professor asks, in a patient, reasonable tone of voice. “Would it be okay if Stevie and I had a little whipped cream? Straight from the can, like real men eat it?”

I shake my head at him, wag my finger. I mouth the words “Not now.” He wrinkles his forehead, perplexed. What is his uncle’s problem? Ann’s shoulders shake more, but she says nothing.

“Just to take the edge off,” The Professor adds. He has learned too well.

Ann spins around, which makes Iris’s eyes widen with alarm. “Jesus Christ, Steve!” Ann yells. Of course, Iris bellows and screams again, louder than ever. Ann weeps angry, bitter tears. Isaac and I march upstairs, where we discuss rogue elephants and snow leopards.

“I’m worried about your mom,” I whisper to Isaac, after he falls asleep.

June 2014

“I’m loving this,” Ann says, as we jog up the Colorado Trail, where she had wanted to go our first day of training. We have come here the past four days. After the Miller Middle School track kerfuffle, I acceded to Ann’s demands, so every afternoon we drive five minutes, then run two miles on the Colorado Trail, one mile up, one mile down. We run along the banks of Junction Creek. Sunlight filters through the forest in resinous patches, and the shade keeps us cool.

The first day it takes 31 minutes. Yesterday we were down to 26. Ann made it downhill in 11 minutes. I have offered nothing but positive reinforcement. The great Soviet champion Krushakoff has not joined us, but I did slip up once and hum the Rocky theme song, until Ann told me to shut it. She actually used that phrase, “Shut it.”

On the upside, my plan seems to be working. A little.

“I’m actually looking forward to runs now,” Ann says. “I always feel better after. And if I can do this—running almost every day and actually enjoying it—imagine what else I can do. Maybe I’ll go to law school!”

The days fall into an easy rhythm. Ann and Steve and the kids have breakfast, after which Steve drives to the fire department and Ann heads out to give massages and to shop and garden and cook and clean, and Isaac heads to off-season cross-country practice. As he walks out the door, I see his forehead wrinkle, which makes me worry. I catch up on sleep, because I’m sensitive to jet lag and because it’s good for anxiety. Iris reads after breakfast, then wakes me at about 9:30 and we walk to a downtown coffee shop together.

Every day Iris and I spend a few hours at the coffee shop, talking, reading, discussing how running has changed Ann.

“She dresses like the other women do in Durango now,” Iris confides during one of our mornings together. “Before there was no way she would go out of the house before she put on a vintage dress. Now she wears tank tops and running shorts, just like the other jocks. Sometimes she even puts on her tennis skirt.”

Iris has inherited her mother’s sense of style. But her taste is different. When she wakes me, she is already dressed for morning coffee. One day it’s in a 1940s vintage red polka-dot shirtwaist dress with black ankle boots and a vintage black beaded purse. Another day a black bolero with a black spaghetti-strap shirt and high-waisted skirt. Yesterday was a magenta cashmere sweater with a black velvet beaded scarf and black leggings. Today she keeps the scarf and adds a 1940s-style straw hat and lacy loose singlet with skinny jeans and white rimmed sunglasses. My heel-hating, no-to-nail-polish sister has created a daughter who wants to wear mascara in sixth grade (Ann said, “No. No friggin’ way”). When Iris orders her coffee at the Steaming Bean on Main Avenue, the woman behind the counter says, “What do you really want, you wild thing?” and Iris fixes her with a stare, and repeats, very slowly, “A cup of coffee, please.” Sometimes she looks like she just stepped out of Teen Vogue. Other times, I worry she’s getting too close to Jodie Foster in Taxi Driver.

Iris isn’t the only one who’s grown up.

The ex moved down the mountain to Durango, too, and while he still rock climbs and skis, he also works full-time, for good pay, owns a home, has the kids half the time, cooks for them, and takes them camping. Isaac has grown into a 15-year-old philosopher who seems to possess an exquisitely calibrated mechanism by which he judges himself and falls short. He frets a lot. A high school junior, he is worried about where he’ll go to college and even though his mother and his father and his stepfather and uncle tell him to relax, not to put so much pressure on himself (he’s a straight-A student, popular, almost six feet tall and slim and sinewy, blue-eyed like his mother, unambiguously handsome, and a proud member of Durango High School’s powerhouse cross-country team), he laments that “unless I discover a cure for cancer, or win a Nobel Prize in astrophysics, I don’t have a chance at getting into the schools I want to go to.” In his forehead-wrinkling distress, he reminds me of me, so naturally I worry about him. I tell him that sometimes I spend time dwelling on stupid decisions I have made, obsessing about horrible futures, and his eyes widen. “You do?” he says, and I admit that yes, I do, and it’s a waste of time and he’s a great kid and he should enjoy himself and maybe tomorrow night we’ll go see an action movie and get sundaes with whipped cream. And that seems to cheer him up.

So does running. I like to think that I helped turn him into a runner. Along with predator tales, I have for years fed him a steady stream of tortoise/hare, David/Goliath, nervous-underdog-defeats-gifted-Adonis-and-finds-joy-and-peace stories. I have told him how I was a nervous, tentative basketball player when I was 12, that I once was so rattled I shot at the wrong basket in a game, but when I learned to stop tormenting myself about outcomes and to just enjoy myself and do my best, I discovered some relief. As a bonus, I performed better.

Does he grasp the subtle Zen trick I’m suggesting? I’m not sure. He so wants to succeed. He is so hard on himself. I hope that a no-pressure fun run in the desert, away from competition and the juggernaut that is the mighty Durango High School track team, might relax him a little bit. That he might find some of the relief I found in basketball, that I still find in leisurely runs and afternoon naps (Isaac is not a napper; I have mixed feelings about that).

Iris I don’t worry about so much. She stopped screaming soon after she learned to talk, unless the family was at a restaurant and her hamburger was slow in coming, which is when she would shriek, “Where’s my meat?” Her favorite phrases starting at age 2, which she still uses often, are: “I’m very upset!” and “Seriously!”

“Science quiz!” I yell at my niece one day in the middle of one of our morning coffee sessions, as she’s engrossed in a fantasy book set in modern-day New York (she usually can finish at least one novel during our morning sessions, and another one before she goes to sleep at night). “What’s the one thing we get from the sun that helps us stay healthy.”

“Vitamin D,” Iris says. “That’s easy.”

“Science quiz!” I yell again, because I want each question to be special, to encourage learning. “What’s better in your uncle’s famous cookies, semi-sweet chocolate chips or milk chocolate? And bonus science quiz question: Refrigerate the dough the night before, or go straight to the oven?”

“Another easy one. Semi-sweet, no matter what some people say. And refrigerate, of course.”

No way will she get the next one. After Isaac, Ann had given me clear and explicit orders about what I should and should not discuss with her daughter. But she needs to be challenged. Isn’t that what uncles are for?

“Science quiz!” I shout, one final time for the day. “How does the mighty and fearsome saltwater crocodile kill its hapless prey before eating it?”

Iris pauses, blinks her alien-sized, South Pacific sea-blue eyes, purses her lips. “Um, I think it’s something called the death spiral. Isaac told me that.”

I stare at her, overcome with love. For her, and for The Professor, and for my sister and her husband and even her ex, remembering those long-ago winter nights of shrieking and meteor talk, forgetting, as I always forget when I hang out long enough with Ann and her family, that I’m still single, that I need to lose weight, that I live in a too-small, too-expensive studio apartment, that I’m bald, that my savings are dwindling, that I still spend too much time fretting about failure and death.

When I’m with them, I have more important matters to consider. “Okay,” I say, “who do you like in a fight between the croc and a pack of ravenous hyenas?”

Iris smiles.

July 2014

Midmonth, I receive an alarming email in New York City. It’s from Ann.

“I have not run for five days,” it reads.

A pinched nerve, the chiropractor had told her. Probably aggravated by the running, but with origins in hip misalignment due to Ann carrying Isaac on her hip for the first two years of his life.

Ann says she won’t be able to run for the next month. And then, the most disturbing passage:

I love how I am feeling in my body. A deep unwinding.

I like the pressure of not having to run.

I like the relief of not timing myself.

I like the no lungs burning.

I like eating chocolate bars and not caring if I get fat.

I like not being able to talk about my running.

I like saying to myself, “I don’t think I am a runner.” It is kind of like saying, I don’t think I want to live in the suburbs, or wear stockings, or work in an office. Somehow saying I am not a runner feels true to my maverick self. Maybe I am a loser because I do not like to run. Or maybe I am just not a runner. I am not a drinker or a smoker either. Maybe being a runner is kind of like being a smoker or a drinker or a super organized person. Maybe there is a gene that makes you be all of those things. I know a lot of runners were smokers etc…

I don’t know.

I LOVE NOT RUNNING.

Sweating, breathing hard, I quickly email back: “A few weeks of rest will be good. Recovery is important. This will make you faster than ever.”

She replies, “I don’t think I am a runner. But I will remain open to see what happens.”

I profess nonchalance about whether we run or walk or crawl, stressing that the important thing is that we do it together, that we move outdoors and enjoy ourselves and bond. I wonder if she believes my lies. There’s no way I’m flying out to Durango, then driving five hours to the Hopi reservation, to stroll 3.1 miles. I am going to get her to run, no matter what.

August 2014

She is running. Still, I’m worried. Three miles in, I took her advice, left her alone, passed about 10 runners and am now ascending a gentle rise. I look back, squint at a long, shuffling line. I can’t see my sister. I’m panting myself. I’m sweating, too. I continue to scan where Ann should be. The runners I had passed now pass me. I take a breath; start running back toward the starting line.

When I find her, Ann is gasping more than ever. She is still scowling. I’m worried about her, and I’m worried about Isaac, who disappeared from our view after the first quarter mile. Is he enjoying himself? Is he pushing too hard? Will he take away fond memories of the day, even when the swiftest Native Americans, desert veterans familiar with the terrain, defeat him? Or will this be one more episode to ruminate upon and worry about? I can’t do anything about The Professor at the moment. I need to focus on my sister.

“Are you okay?” I ask.

“I just had the most incredible epiphanies!” she gasps.

“Really?”

“Yeah, you know how Mom is always asking questions about how food is prepared, and reading street signs aloud whenever we’re driving somewhere and always interrupting and asking questions and complaining and wondering whether there’s Internet connection on the reservation? It’s because she probably never got her needs met when she was a little girl and now needs attention.”

“Hmmm,” I say. I wish Ann would pick up her feet more. There’s something so willful and contrarian about her shuffling.

“Want to hear my other epiphany?”

“Sure.”

“You know how much I love it here? And how at home I feel? After about two miles, just the last few minutes, as we’ve been climbing, I realized something: I was a Hopi man in another life!”

Should I stay with her the rest of the race? Is she about to collapse from heatstroke? Or might this be her second sight at work? (Once, years earlier, she had watched gigantic faces of Mayans slide of the Comb Ridge rock formations near Bluff, Utah, “like someone was projecting huge movies or something.” It was about a decade before scientists released studies suggesting that Mayans had, in fact, likely been there. Maybe my little sister had been a 19th-century warrior. Or medicine man. Or whatever.) But what if it was heatstroke?

“Cool,” I say, because as her coach I want her to feel comfortable. “Um, Ann, remember what I said about how when you’re going uphill, you should shorten your stride, because it makes it easier, and then after you reach the top and start. . .”

“I get to run the race however I want to run the race!” she yells. “You don’t get to decide. I’m the boss of me.”

Fierce will, or lack of oxygen to the brain? With my sister, it’s never been easy to ascertain.

“Um, Ann, did you just say ‘I’m the boss of me’?”

“Go,” she hisses, “just go.”

“You have such a nice stride,” I lie. “If you just kind of picked up your. . .”

“I’m happy,” she says, though she looks anything but. “Go. Go!”

How can I?

“I am fine,” she says. “I’m better than fine. Just go run your own race.”

So I go. But I worry.

I crest the little hummock, descend, look up, and half a mile ahead, I see a set of steps so absurdly steep (they are hundreds of years old) that everyone walks, rather than runs, up them. For some reason, the worry is abating. Ann is running, I’m running. Isaac is running, far ahead of us, and I hope that he’ll remember the desert beauty and not the sun-scorched details of his late-summer failure. Steve the fire captain is running, too, in the 10K. Iris (purple Converse, cream-colored flowered shorts, white tank top) and my mom are walking the mile fun run. I run toward the steps, and the sky is vast and soft and the desert stretches forever and the hard, clean light feels good on my skin, and I can see the blue corn breakfast burritos at the Hopi Cultural Center Restaurant & Inn awaiting me after the race, and I know that without my adventurous if sometimes difficult sister, who had invited me West, as she invites so many people, without her listening to me complain and telling me to drink water and to be kind to myself, as she does with so many people, I would be in New York City at the moment, alone, anxious, waiting for some Chan-Do Chicken to be delivered from Shun Lee West, staring at episode 29 or 33 of a French crime drama whose anti-heroine, the redheaded and morally compromised lawyer Mademoiselle Karlsson, intrigues me. What kind of life is that? Isn’t it better that I’m here, in the desert, with people I love?

I wheeze, sloth step by sloth step, up the killer rock stairs and then start another descent, breathing evenly, smiling, hoping that my possibly psychic, possibly medically compromised, definitely spunky little sister is okay. I think about how happy I am when I’m with her, even when I’m worrying about her.

And that’s when I have an epiphany of my own.

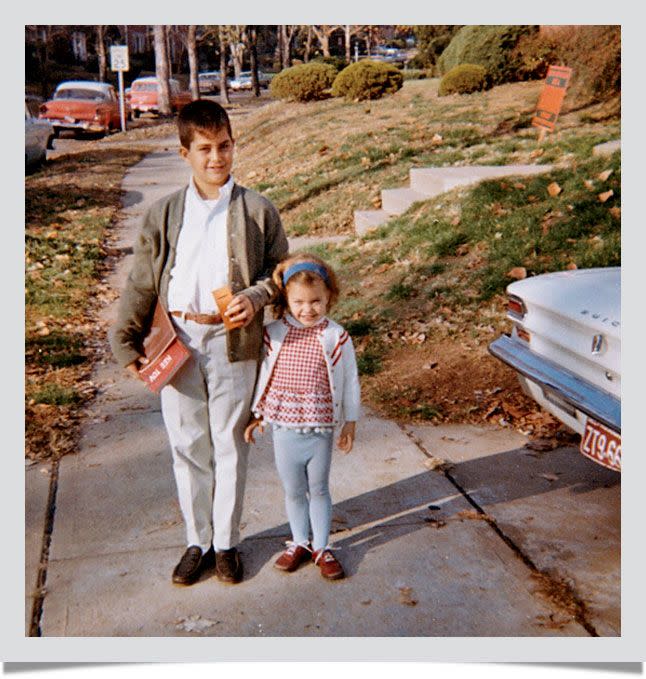

June 1961

I am 6 and a half years old, peering into the crib at my 6-month-old sister, who has casts on her legs and feet. She is clicking them together and gurgling and laughing. I am an anxious child, afraid of bugs, birds, tomatoes, fish, mustard, radios, and Wendy the beagle who lives next door and who everyone says is friendly. I hum when I’m eating and blow spit bubbles to soothe myself. On rainy days I sob and beg my mother to let me stay home because I know that worms will be squirming all over the sidewalk and I might accidentally step on one, but she refuses.

I reach into the crib and pet the baby’s head. I worry about the baby because of the casts, which she got a few weeks ago because her feet pointed funny. They were pigeon toed, or like a duck, I can’t remember. Mommy and Daddy said not to worry, the baby would be okay and the casts wouldn’t be on forever, but they always said not to worry. I still had to go to school on wormy days. And she was so little, and the fact that she wasn’t even sad about the casts—that she was smiling at me and wriggling and gurgling and laughing and now squeezing my fat butterballish first-grade fingers—made me even more sad.

I spend a lot of time worrying about my little sister. If I worry about her, I don’t have to worry about the pink and brown sidewalk worms, or having to go to the bathroom at school, or whether I might throw up in class, which I have done twice already this, my first-grade year. If I worry about my baby sister and her sad casts and what is going to happen to her, I don’t need to be scared of whether the fifth-grader Jimmy P. might beat me up for looking at him funny, and I don’t have to worry about whether I’ll mess up in kickball again and get in trouble with Mr. S. the gym teacher who tells me I’m lazy just because I can’t run fast and who I saw grab a sixth-grader by his shirt collar once and lift him up and scream at him, or whether my first-grade teacher will be “concerned” when I print the alphabet wrong again (I leave out the letters between K and P because I think it’s a special P, an elemeno P). Worrying about Ann, I don’t need to worry about whether Mommy and Daddy will argue at breakfast over whether the eggs need ketchup (“You’re going to put ketchup on them before you’ve even tried them? Won’t you at least try them first?”), or about whether I’ll have the bad dreams about the monsters again, or whether, when I’m walking in the alley behind our house, Wendy the beagle who everyone says is friendly will yawn at me and show me her big teeth which made me have an accident once, or whether the fat boy in the wheelchair on the back porch up the steep steps at the house across the alley from Wendy the dog will moan at me and roll his head, which made me have an accident another time, and that night Mommy made me Bonnie Butter Beef hamburgers, my favorite, but she said I was a big boy now and I didn’t need to be so scared and then I cried because I thought I was in trouble for the accident and I had bad dreams.

I’m a scared little boy, but standing next to baby Ann’s little crib (Where are our parents? Where is our big brother, Donnie? I have no idea.), I stare at my little sister with her hard tiny casts and the way she clicks them together and giggles, and I worry about Ann and feel sad for her with her little casts, even though she doesn’t seem worried at all, and sometimes I tickle her tiny bulging pink belly and she gurgles and smiles and then I don’t worry about anything, even Wendy the beagle or the fat moaning boy who Mom says was “born funny and we should all be nice to him because for that family it’s a cross bear,” and he doesn’t look like a cross bear but still, he scares me.

Ann grows up strong and brave and beautiful, and even when she beats her boyfriend in the 50-yard dash in sixth grade and he breaks up with her the next day, she yells at him but doesn’t mope. And when her friends in junior high school play dress up and draw hearts, she comes to watch me play basketball and pores over Our Bodies, Ourselves (my high school girlfriend gave it to her for her 12th birthday), and when her fellow high school graduates join sororities and buy Laura Ashley dresses and marry accountants, Ann moves to California and dates shoeless musicians, then she makes a life in the mountains of Colorado and takes wild risks and fails sometimes but keeps taking them, and whenever I call because I’m worried about her, our talk usually turns to my anxiety about a recent girlfriend, or an upcoming assignment, or money, and Ann asks whether I’m drinking enough water and whether I’m doing the downward dog, because I should really do both and I’ll feel better, and when I’m really sounding bad, she’ll say, “Television and ice cream seem to soothe you, so that’s okay, too. Don’t beat yourself up too much.”

It always sounds so simple.

August 2014

“That was awesome!” Ann exclaims. “I loved that! I want to do more races!” She finished in 42:27, in 114th place out of 153 runners.

We are descending the Mesa, driving away from the reservation, toward home.

“I’m so glad to hear that, Ann,” I say. “As a coach, that is gratifying. Next time, if we tweak your stride, and concentrate on negative splits, and…”

“But only races run by Native Americans. Races that are mellow, where it’s all about togetherness and people getting out and exercising together and having fun.”

“Ann, most races are like that, really. You don’t have to limit yourself to ones sponsored by Hopis.”

“Yeah, right, Butterball,” Ann says.

“Really? After all that?”

Her husband, a man of strong deeds (he finished the 10K in 1:14:44, 125th out of 173) and few words, speaks up from behind the wheel. “Your brother is right, Ann. They’re not like those crazy cyclists, or the cutthroat triathletes. Runners are really a very mellow bunch. They tend to help each other at races. You could do almost a race a week without leaving Colorado.”

“Really?” Ann asks. “Wow. Hmmm.”

Alone in the desert, six of us under a vast, blazing sky, sealed in by glass and metal, skimming past washes and sand and dirt. Ann sits behind the driver’s seat, and she can’t stop smiling. Next to her, my mother, who mentions, when we pass a dusty old trailer with a dusty tricycle squatting in its yard of dirt, “I could never live like that, Honey,” which prompts Ann to chuckle and say, “Has anyone asked you to?” I’m in the back seat, still feeling a little woozy from my final sprint (I finished at 41:35 in 111th place), and on my lap is Iris, who wants to know when we can stop at a gas station for some beef jerky, because she is hungry. Seriously!

Asleep in the front seat, his head against the passenger window, slumps Isaac. In his lap he clutches the medal and the handmade Hopi woven plate he received for winning the 5K race. “First,” he told me, grinning, when I found him at the finish line. First in the 16- to 19-year-old age group. First overall. He beat everyone. He finished in 22:46, more than a minute ahead of the second-place runner. I lean forward to gaze upon my sleeping nephew, my anxious, self-punishing, needs-to-find-the-cure-for-cancer-if-he-has-any-hope-of-gaining-admission-to-the-college-of-his-dreams nephew. Did he relax and enjoy himself? Did he run free of imaginary burdens, with rapture? Or did fear dog his every stride? Did bottomless need fuel him? I watch him breathing evenly, smiling in his sleep. His forehead is smooth as a river-washed rock.

October 2014

Ann continues to run and Isaac continues to compete in cross-country and, as far as I can tell from our phone conversations, continues to worry about college and meteors. He and his father pull an enormous tree trunk from his father’s yard, and together they build a tool shed. Iris reads 14 books over the postrace week and a half and then announces that she’d like to spend a few days in New York City this winter with me, and did I think I could get her tickets to Fashion Week? And maybe a tour at Elle magazine? And some theater tickets—she hears there are some intriguing (her word) off-Broadway productions opening? My mother returns to Portland, from where she calls Ann regularly and asks if she has thought anymore about getting a dishwasher. Also: “Honey, promise me you’re not going to move to that reservation.”

I fly home, where in addition to running four times a week in Central Park, I wear my pale gray rubber Louis Tewanima Footrace bracelet and try to drop into every conversation, no matter the nature of the topic, ever so casually, that “Oh, yeah, I ran a 5K on a Hopi reservation.” Once, to my horror and shame, I actually say, “They’re a peaceful people.” I watch too much television in my studio apartment while I think of potato chips and sleeping rescue dogs and science quizzes and my family in Colorado.

When I’m feeling down—and I still feel down sometimes, who doesn’t?—and a run doesn’t snap me out of it, I take a nice afternoon nap and before I sleep I close my eyes and summon the moment on the edge of Second Mesa just before I started to sprint for the finish line, the instant right before I spent 50 yards battling a 7-year-old girl in pink shoes (she was finishing the mile fun run, but we were aiming at the same finish line and she was booking), defeating her but almost puking in the process.

The magical, nourishing moment I summon: my final look back, just before I take on the 7-year-old. That’s when I see Ann. She is climbing the steps carved into the rock. She’s smiling. She’s talking to some of the other runners. Not only talking, but passing. She passes at least seven runners. Is she laughing? I’m not sure. What I am sure of is something even more amazing. She’s not walking, or straining up the homicidal steps that have reduced nearly every runner in this race to a labored, stooped schlep. She’s running. She might say jogging, but that’s because she’s stubborn. That’s because she spits on anyone categorizing her, on anyone who has ever categorized her. She’s running up the brutal steps. She looks so happy. So content. Maybe I don’t need to worry about my sister so much. And if I don’t need to worry about her, maybe I don’t need to worry so much about my studio apartment and what an ex said seven years ago about how much I liked television and the inexorable passing of time and stupid decisions I have made and stupid decisions I will certainly make in the future. In the desert, under a windless sky and a cleansing sun, it occurs to me that worrying about my sister has been a distraction I could finally let go. It occurs to me that I never needed to worry about my sister. I watch my sister run, delighted, unconcerned, and I turn to run myself, and I think that maybe I never really needed to worry about anything.

Story Update · June 9, 2016

“Ann is an artist,” says writer Steve Friedman of his sister, “so she’s always been very accepting of what comes out in the writing process.” His niece, Iris, however, wasn’t quite so welcoming. “Let me get this straight,” Iris said to Friedman, “Isaac [her brother] is athletic, sensitive, and brilliant—and I cried a lot as a baby?” Friedman made it up to her with a day out together in New York City. Iris now reads a book a day, and recently got a full scholarship to a private high school. Friedman hung with Isaac, too, catching up on The Walking Dead over pizza. Isaac helped his Durango High School cross-country team win the Colorado 4A state championship last fall and will be attending Middlebury College this fall. (He’s undecided about running competitively, but plans to pursue writing—and neuroscience.) Ann hasn’t run another race since; if she does, it will probably be the Louis Tewanima Footrace again—and Friedman says he’d like to go back, too. The process of getting ready for and ultimately running it with Ann, he says, “helped us get closer and really let me see her strength and our differences, and how much we love each other.” –Nick Weldon

You Might Also Like