Sies Marjan Makes Advanced Menswear Look Easy

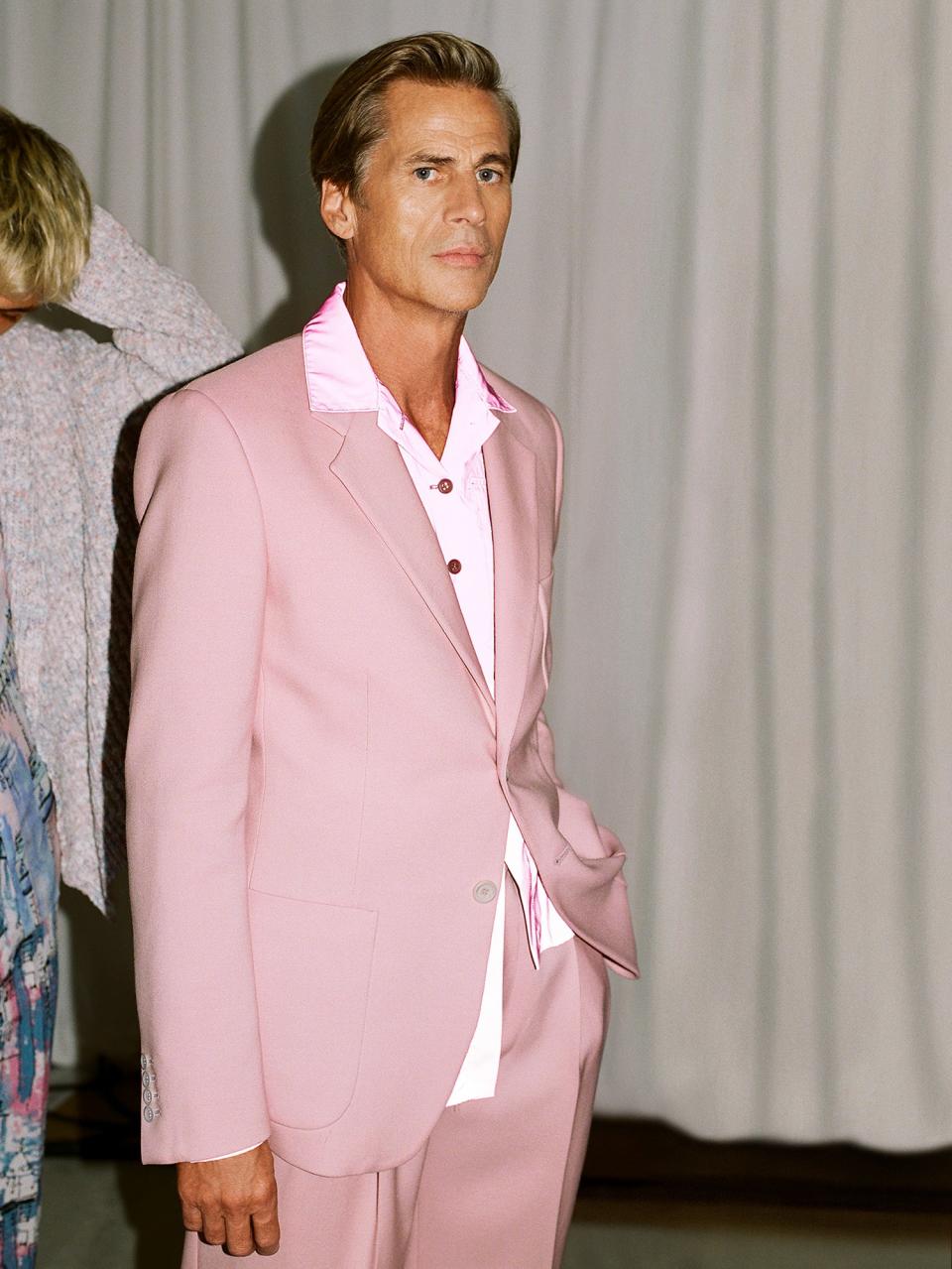

Sies Marjan launched in 2016 as an instant, out-of-nowhere fashion sensation, with big buzz behind designer Sander Lak (who previously spent five years working in Belgium for Dries Van Noten). The men's line began as a small companion piece to the women's and has since thrived, thanks in part to Lak's vision—and timing. Sies Marjan broke out by not fitting too neatly into one of menswear's pre-existing camps, with a finely tuned sense of color and texture—see: pajama shirts in jewel-toned silk and velvet with crinkly textures and psychedelic ombré prints.

Now seven seasons in, Lak has established Sies Marjan as one of the great New York fashion labels. I met him a few weeks back at his midtown Manhattan HQ, where his team of pattern makers, cutters, and sewers work behind a large glass wall that separates a lounge area from the atelier, to talk about his growing business and the state of menswear today.

GQ: It's serene in here, even though you have a factory at work right next to us.

Sander Lak: Normally, the atelier is a hidden part of the company. We really wanted to put it in the front. So when you come in, you're already seeing what they're working on. We're just making clothes. If you see a little bit of what we're doing for the next collection, who cares? That's not that important. It's more about this idea of opening up that space—not just for people like you to come in and to be impressed, but also for [the workers] to see what's going on and to see the appointments that we have here.

It's a little bit like the idea of the open kitchen in a restaurant. When you get to see the chefs cooking, you know that they have nothing to hide.

Exactly. But it's also, for the chefs, interesting to see people eating their food.

So how much was still here from when it was Ralph Rucci’s atelier?

We completely renovated the space. There's nothing left except for this bookcase thing [that] was here, but everything else we completely changed. We really rebuilt it into our own space.

And the same staff that was here before?

No, only sewers and some pattern makers stayed. That's really the most valuable part for me, because these people have skill sets that are unheard of in the industry. And it's really great to have them work on the kind of clothes that we do as well. They're used to making couture, and now they're doing a very clear ready-to-wear kind of thing.

Do you find yourself sort of collaborating with them on designs?

Yeah. I've learned a lot about finishings and about how to actually make things look expensive to an extent that sometimes, with ready-to-wear, you're not able to, because hand-stitching is ten times more expensive than a machine stitch. So how do you make machine stitch look as if it's a hand stitch?

How has it been different or the same as what you expected when you started?

I do everything by gut feeling. So when I decided to take this opportunity—this kind of strange, very abstract and very unclear opportunity—my gut feeling was telling me that this was the thing to do. I've worked in the industry for a while, so I've seen a lot. I've seen really good things, I've seen really bad things. I've seen people crash and burn. And I also knew that I shouldn't see more, because at some point you need to be naive in your thinking. You need to pretend that everything is possible, because if you are in an industry for too long...it's compromise after compromise after compromise after compromise.

Because there are commercial needs?

Yeah. Nobody needs any of this stuff. So you're providing the illusion of the need. And it's not like art where if you're a good artist you provide something that is beyond that commercial need, something that really is meaningful. As a designer, in my point of view, that is just not the case.

That's why after a while you get a little bit like, “What's the point?” With Sies Marjan I was like, “Just shut up. Anything is possible.” And I think that naive kind of spirit, which I still had, was needed.

So how do you like being in New York?

I was born and raised abroad, around the world in so many different places. So the physicality of a place is not really an issue for me. If somebody would say you have to move to Hong Kong tomorrow, I'll pack my bags. I've done it so many times.

Here we go again.

I’ll be able to speak the language at some point and know the culture. It's very easy for me. That's the way I've been raised. It took me like two years [to adjust to New York] because it wasn't just the city. All of a sudden I had this life that I never had before, responsibilities I never had before, and a job that I never had before. But now I feel at home. I feel this is the place where I want to be, this is the place where I want to stay.

You like the job?

Yeah. I love the job. I feel like everything has led up to this moment and I feel all of my strengths and all of my weaknesses are perfect in what I do. Am I always doing a great job? No, but it's more about what I feel emotionally. I try to be inspirational. I try to motivate people. I work in a way which is very Dutch, very direct and open. You'll get all of this open communication and that's really how we work.

You’ve lived all around the world—The Netherlands, Belgium, Malaysia, Gabon, Scotland, Paris, New York. Do you find inspiration in these places? In the idea of being a world traveler?

I don't really do inspiration in general. It's all gut based. I might put a board together but it's more for references for my team. But it's never like, this season is all about my time in Malaysia combined with, like, a Picasso exhibition. It's never that flat. I've done collections based on very clear references and it's really great. I just don't wanna work in that way, I find it very limiting.

Everything is very personal and sometimes I don't know why certain things are the way they are. It's only now that I understand what this Spring collection is about.

So what is this collection all about?

Initially, I really thought it was about home, and about New York, and about family, but actually it's 100 percent about my Dad, who is not around anymore. Everything in this collection is about what my dad used to wear, what my dad looked like, who my dad was, how he lived his life. And it's really interesting because I didn't see that at the time, but it is about him and about letting go. This is all of the stuff that he used to wear—these colors, when he lived in Saudi Arabia and Qatar he would wear like khaki pants, military stuff. And he would wear Ralph Lauren Polos and stripey sweaters.

What was his profession?

He was an engineer and he worked on the oil platform, so it was a very rough job. We traveled with him.

Did you grow up thinking that you'd be an engineer?

No, I wanted to be a film director. I wanted to be a painter. I never was interested in fashion. I didn't really understand fashion at all. It was only in my teenage years that I started understanding what it actually was. I discovered fashion through my own connection to clothes. Not a fantasy. It was always about wearing things and being like, “Why is this pocket shaped like this? I don't get it. Why is my friend’s pocket different? Who decides if it's a rounded shape or a square shape.”

You named your label after your parents. Tell me about that decision and how it feels now.

I'm a designer. I don't care about fame or recognition. I'm confident and I know what I can do, and I know what I can't do, and I don't need to have my name on it for it to be valuable. I don't think it will do me any favors. The fact that my name is kind of behind a wall makes me feel protected in a way.

I hate those names that are sentences that don't make any sense. It has to be personal. It has to be connected to me in a very direct way without it being my name. Then we ended up like, wait a minute, what about your parents? My father's name is Sies, my mom's name is Marjan—how it looks, the fact that nobody here knows it's male or female, [or] where it's from. It could be from anywhere. Immediately I was like, that makes total sense. For 99% of the people that see our clothes in the store, they will think Sies Marjan is a person from somewhere and that's perfect.

That said, it's a very personal thing because my dad Sies died when I was younger and it was very emotional for my family. And to go even deeper: I'm gay; I don't think I'm gonna have kids. I don't think it's for me. This is kind of like my child. All my brothers have several kids, and they all contribute to the family and for me it was a little like, well this is what I can contribute.

And lots of people do name their kids after their parents or someone else in their family.

It also needs to work from a market point of view. Visually. And from a communication point of view, if you hear that story it immediately tells you who we are as a company. It immediately tells a story of how connected we are to a person, to a feeling, to a family, it immediately gives it a beating heart.

It’s human.

It's human as opposed to it being this thing that just provides a product. I don't wanna spend this much time and this much blood, sweat and tears on something that doesn't come from a real place. Otherwise, I'll just cash in and work somewhere and make some shitty T-shirts and just make shit ton of money.

What’s your view of the way men dress today, and what are you proposing for them?

I always think about what I want and what I can't find. When you go to a department store you have your chunk of, let's call it streetwear, you have your chunk of dark, European, like Rick Owens kind of intellectual stuff—which is great and beautiful. But specific. They have a little corner of fashion stuff which is just kind of weird and that's it. There are camps and you have to be in one of them. And I've never been any of them. I love parts of all of it and I don't like parts of certain things.

Once you really look at what we offer—it's still small, it's going to grow a lot—it's very much about the tectonics of fabric and color in styles that are really easy to work with. It's not about overcomplicating things at all. Sometimes a really beautiful color and a really beautiful material is enough. I'm confident enough in what I do that I can strip back to what is needed to make the garment best. I don't feel for every garment that I need to overcompensate and show my skill set, like I need to show what I'm capable of. And I think maybe that gives the product an ease, even though there is a complication to wearing certain colors.

What do you mean by an ease?

All day long you are in a pajama type of feeling even though you're not actually in pajamas. I think that's something that men have really reacted to. Men are also really reacting to all the extreme pieces—like the pink fur jackets or the super bright purple pants, which sold out immediately. And these are straight guys who are kind of trying to figure out who they are as men. And because in the #metoo movement, men are sort of confused—straight men are sort of confused about who they are, what they are, and how they stand. The solution, maybe, is wearing a pink fur jacket because that shows another side. And I think that's really great.

The way men dress now, especially in America is changing so quickly.

Because men are changing,

And I feel like you have to some extent really nailed the timing. Five years ago, the type of men's fashion you're doing now may not have worked as well.

Which is a lucky situation. It's not like I'm calculating. When we put out the first collection I started seeing the results really quickly. It went so fast. And then I was like, of course, this makes total sense—everything I'm saying about what's happening with men and masculinity and [the] male sex… Fashion used to be a niche thing for the fashion guy and that's just not the case any more. There's so many of these guys that are so masculine, it’s so clear who they are as a man and somehow this expression of putting clothes on themselves makes them appear to be more masculine, more attractive. Because they don't give a fuck. I think there's something really great about that. And that wasn't the case five years ago.

I think a lot of designers and brands are grappling with these issues right now. How to make clothes for men today.

The hardest thing to do is to not design. And that applies to everything, but especially to menswear. You have to know when to stop. It's like making a meal. Like making a soup. You can use five ingredients, you could use 50 ingredients. Most of the time the 50 ingredient soup is gonna be a little messy.

You mentioned that Sies Marjan men's will grow. What’s the plan?

We're just exploring what we can do with men's and we're going to grow the business. It's very clear that it has a lot of potential. We’re really gonna expand the range. We will try something and if it works we continue and we grow it, and if it doesn't work and we still believe in it, we try it again. And if it doesn't work then, we just drop it. We're very organic in that way and menswear is something I was just like, I need some clothes, let's just put it out there. Then it blew up. So now we're like, okay, well, obviously this is working, so let's take the next step. And because of the independent spirit that we have, we can do what we want.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2019 issue with the title "Sies Marjan Will Sex Up Your Wardrobe."