Shane MacGowan Will Outlive All of Us

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

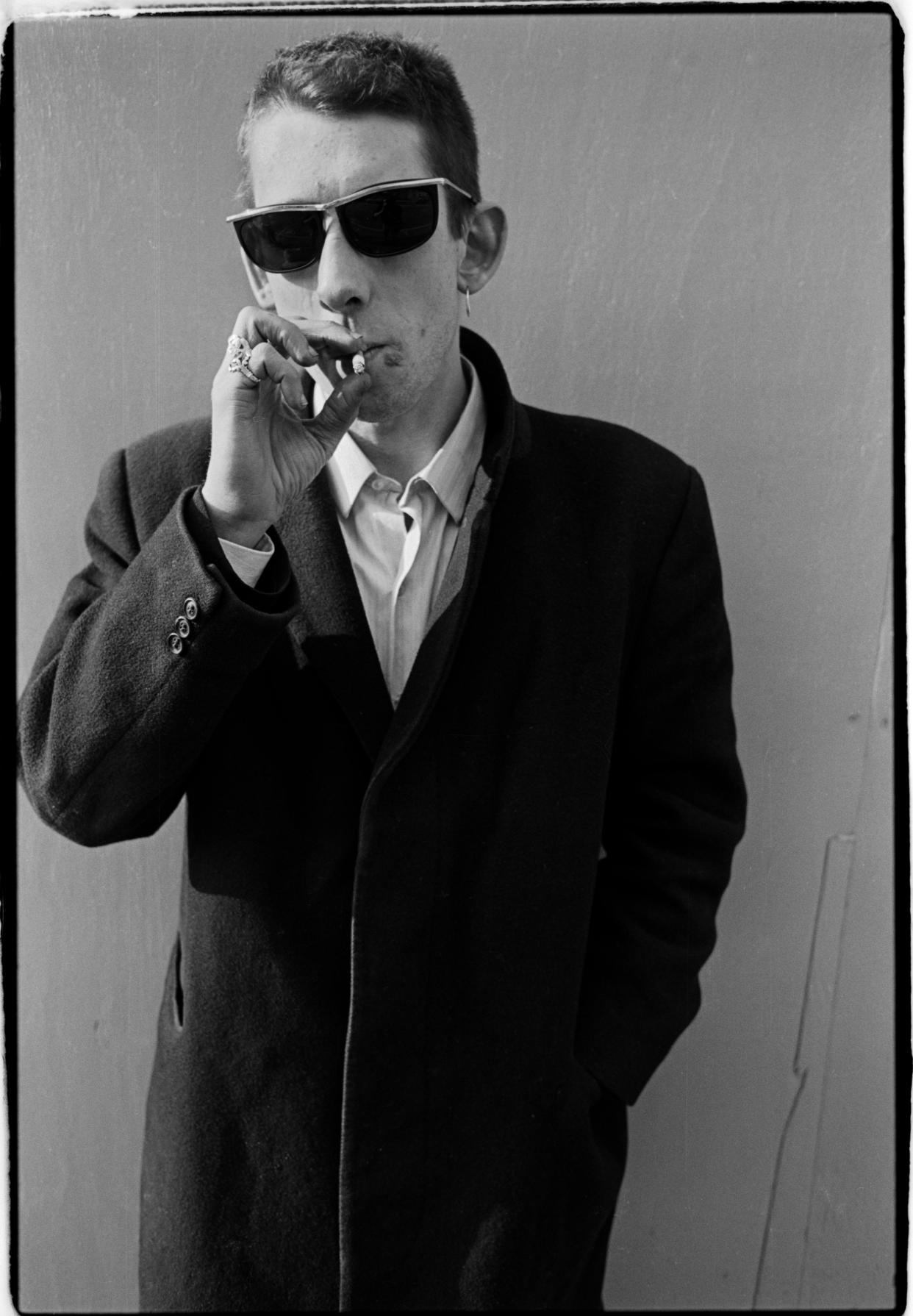

David Corio

It’s almost 11 p.m. on Halloween in Los Angeles, the openers are done, and there’s a tension in the air, this electric hum: Is he going to make it? Is he even in this city? Nobody really knows. You look at the roadies for clues—first to figure out if your ticket was worth buying, then to figure out if the man you came to see is actually alive. This isn’t theater, some communion between performer and audience; it’s legitimate anxiety. Middle-aged Irishmen, Londoners, and Boston transplants are all nervously chatting about it. This ticket is—uniquely, even within rock music—a gamble. The sitter, the parking garage, the nine-dollar beers—it’s all a dice roll. It could all be for nothing.

The lights dim. The house music comes on: “Straight to Hell,” by The Clash. The crowd starts optimistically stomping to the beat. The band emerges, in full mariachi costume, which doesn’t stop them from looking like (sorry, but they did) undead pirates. Possibly the most grizzled band to ever exist. Deep breath. Is it really gonna happen?

And suddenly, there he is, lightly swaying to center stage. He’s wearing a sombrero and a bathrobe, lit cigarette in one hand and a glass of bourbon in the other. Not that he’s trying or cares, but he doesn’t look good. He looks like he’s off his ass, yeah—but more importantly, he looks sick. Is this gonna work? Am I complicit in something?

Then he barrels into “Streams of Whiskey” with his full-throated roar, as powerful as ever, and the crowd pops like a balloon. The tension’s gone. This is a Pogues show, and Shane MacGowan is singing. The Ramones are gone. Joe Strummer’s gone. Yet Shane MacGowan is here, verifiably alive. And he kills.

It was my first concert. I convinced my mom to drive me and my brothers to L.A. because it was a cultural emergency. There’s no way Shane MacGowan, one of the great Irish songwriters, will see another year.

That was 16 years ago.

Shane MacGowan died this past Thursday, in Dublin, following a long illness. So many jokes about him, for decades, that he was about to die. And he stubbornly outlived the entire bit. The book Is Shane MacGowan Still Alive? was published in the year 2000. The next year, the Pogues got back together and toured until 2014. In his way, he proved everybody wrong. Maybe furiously gossiping about an artist’s health isn’t the best way to talk about an artist.

If the Pogues had never happened, Shane would have been modestly famous in the London punk scene, for a picture taken of him at a Clash show after he got his ear bitten. You’d think a guy like that would start a band with ripping electric guitars and scream about Maggie Thatcher. Instead, he changed the whole concept of what a punk band could be. Traditional Celtic music. A huge, orchestral sound (their classic lineup was an 8-piece). Religious, historical, literary lyrics. His masterpiece, “If I Should Fall From Grace With God,” is Shane at his most punk. In a genre dominated by contemporary political screeds, he wrote something that could have been written 400 years ago and could be sung 400 years from now.

If I should fall from grace with God

Where no doctor can relieve me

If I'm buried 'neath the sod

But the angels won't receive me

Let me go, boys

Let me go, boys

Let me go down in the mud

Where the rivers all run dry

The myth-image of Shane: drunken hedonist, Irish cartoon who once dropped 100 tabs of acid and literally ate a Beach Boys album. Like all the great trickster-gods of rock music, he winked at this myth just enough to help perpetuate it. But as an artist, he always transcended it. He was a deeply emotional songwriter whose gift was for light-beams of sincerity that shone through a thicket of pained, snarled delivery.

And every time that I look on the first day of summer

Takes me back to the place where they gave ECT

And the drugged up psychos

With death in their eyes

And how all of this really

Means nothing to me

People don’t become known for historic amounts of substance abuse because they’re happy. They don’t do it for fun. It can be fun for a few years, but after that you’re in hell. Shane believed songwriting was about overcoming pain. That he had an artistic mission to make a joyful noise. To find something to celebrate, a communal catharsis. Something all his best work has in common is this sense that if we’re going to hell, we should get our money’s worth first.

Born on Christmas day in 1957, he never escaped being known for a Christmas standard, “Fairytale of New York,” a song he never sang when he toured the western United States. Like Warren Zevon and “Werewolves of London,” if you really like the guy, that song can be deleted and the body of work will remain. Unfortunately, the song is just about perfect, from the Dickensian sweep of the arrangement to the lyrical inventions (there is no “NYPD choir,” but he sure convinces you), to his shiver-inducing vocal rapport with Kirsty MacColl, who sounds as belligerent as a fishwife and plaintive as a ghost.

At the peak of his power, Shane wrote songs as eternal as anything by Hank Williams. He sounded like Johnny Rotten and that always distracted from the fact that he was writing Woody Guthrie songs. His delivery and lyrical content were always in conflict, always generating the friction that made him stick. But it was that sneering delivery of pure Irish balladry that kept the songs from being too sentimental. If he were a prettier singer, I’m not sure I would have believed anything he was saying.

His period of public productivity was short. After 5 albums, and after getting fired from his band in 1991, he was essentially finished. But the songs endure. They’ll outlive all of us. There’s a reason Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen both made pilgrimages to see him in Dublin in his final years, after he became unable to travel. There are very few writers capable of writing songs that feel eternal. It’s him, Bob Dylan, Chuck Berry, Hank, Guthrie, perhaps five others depending on your partisan affiliations. And now he’s gone. Before that, he was in pain. Maybe that’s grace.

Take my hand, and dry your tears babe

Take my hand, forget your fears babe

There's no pain, there's no more sorrow

They're all gone, gone in the years babe

Originally Appeared on GQ