The shambolic Genesis reunion that saved Peter Gabriel from financial ruin

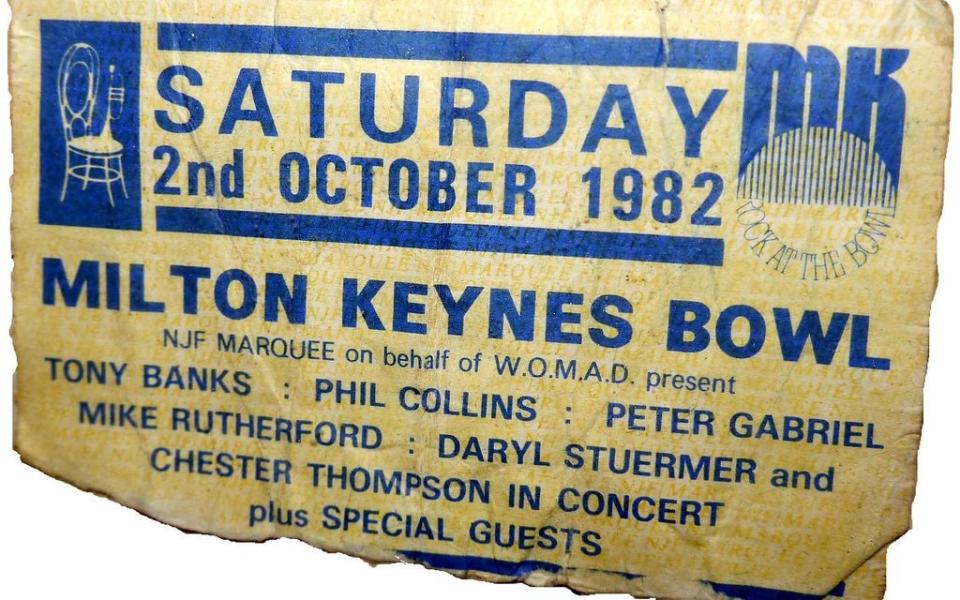

On October 2 1982, Peter Gabriel rejoined Genesis for one night only at a concert at the Milton Keynes Bowl. For legal reasons, the re-union was billed as Six Of The Best, a sleight of hand that did nothing to deter more than 60,000 supporters from descending on a venue in northern Buckinghamshire that was once a clay pit. As befits this most wistfully English of groups, it tipped it down all day.

In an artistic sense, Gabriel had no use for Genesis. In the seven years that had elapsed since his last concert with the band - at the Palais des Sports in Besancon, in France – the 32-year old had invested time and energy in establishing his credentials as a sole trader.

So effective had this process been that the set-list for his North American tour of 1982 featured not a single song from his period with the band with which he made his name.

“Having tried for seven years to get away from the image of being ex-Genesis there’s obviously a certain amount of [trepidation] stepping back,” he told the NME in 1982. “I don’t think they would choose at this point to work me or, or I with them.”

Gabriel told Genesis that he would be leaving their ranks at a meeting at the Swingos Hotel, in Cleveland, on November 24 1974. The fortunes of their want-away singer duly prospered, but so too did those of the musicians he left behind.

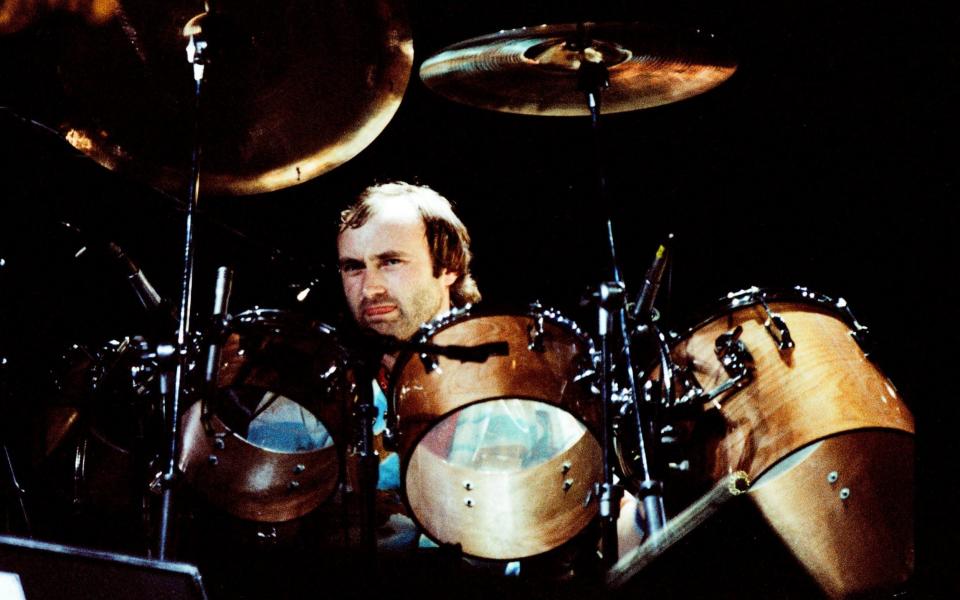

With drummer Phil Collins assuming the role of vocalist, the trio enjoyed their first major hit single with Follow You Follow Me, in 1978. Two years later, Duke became their first album to reach number one.

Unusually, the reunion of the two camps was not informed by the corrupting allure of nostalgia or personal enrichment. Rather, it was the logical response to a pressing emergency – the need to forestall the arrival of bailiffs, and bankruptcy. Putting it baldly, without the help of his erstwhile colleagues, Peter Gabriel would have gone bust. “It’s very generous of them [to offer to help],” he said, “and I’m very grateful.”

The singer’s problems began in 1981 after he met the three publishers of the quarterly music magazine the Bristol Recorder. United by a passion for what would become known as “world music”, the quartet decided to found Womad – World Of Music And Dance – an organisation dedicated to promoting international non-mainstream artists from Chadwell Heath to Chad.

Plans for a compilation album, Music & Rhythm, were put in train with contributions from Gabriel, David Byrne, and Peter Hammill, among others. An inaugural three-day festival at the 240 acre Royal Bath and Wells Showground, in the Somerset town of Shepton Mallet, was announced for the weekend of July 16 1982. The bill featured artists from 21 countries, and included Peter Gabriel, Imrat Khan, The Beat, Simple Minds, Don Cherry, Drummers of Burundi, and more.

The Womad festival featured innovations that would in time become staples of the summer circuit. Films were shown; stage time was allotted to spoken-word performers; food stands included the Simple Simon Wholefood Store, the Portobello Road Sweet Corn Company, as well as concession stalls knocking out wholegrain crepes and Jamaican fish and chips. Ticketholders were also at liberty to purchase items of clothing capable of blinding a child at 40 paces.

But it was doomed from the start. The release of Music & Rhythm met with severe delays, with knock-on effects for the sizable advance from WEA Records. The local authority decreed that the event could take place only in the venue’s Showering Pavilion, which held 4,000 people. The Arts Council declined to provide funding; this being Britain in the 1980s, there was also a rail strike. Inevitably, the weather was not kind.

Worse still, ticket sales were poor. One attendee remarked that “there seemed to be more people walking about with laminate [passes] than there were audience [members].” Realising that they were on the hook for the festival’s mounting debts, all but one member of the organising committee resigned their posts just days before the curtain was raised.

The man left standing was Peter Gabriel. “It became a nightmare experience when we realised there was no way we were getting the ticket [sales] to cover our costs,” he told The Guardian in 2012. “The debts were way above what I could manage, but people saw me as the only fat cat worth squeezing. I got a lot of nasty phone calls and a death threat.

“We naively assumed that we had an event with more appeal than it actually had,” was his wistful conclusion.

Salvation came via the umbilical chord that remained uncut between Peter Gabriel and Genesis. Despite their estrangement, the two camps were hardly warring parties. Phil Collins played drums on three of the tracks on the singer’s untitled third LP, from 1980. As well as this, the band’s manager, Tony Smith, retained a 50 per cent stake in Gabriel’s management.

It was Smith’s idea to get the old band together. But with the weather cooling and time as an enemy, a concert that would ordinarily take 18 months to plan was pulled together in a matter of weeks. Tickets cost £9, or a tenner for those that paid on the gate.

Adverts in the music press made clear that the event was “a benefit for Womad”. “It seemed like a pretty obvious thing to do [but] the problem was logistics,” said bassist and guitarist Mike Rutherford in an understatement worthy of Reginald Jeeves.

In the autumn of 1982, Genesis were approaching the end of the Three Sides Live Encore tour – only a prog band could hit the road in support of a live album – a two month caravan of North America and Europe that pulled up to the loading bays of the Hammersmith Odeon on the final three nights of September. Rehearsals for the show at the Bowl were scheduled for the afternoons of these London concerts.

The task was mountainous. In 1982, the group were used to performing just four pieces from their era with Peter Gabriel – The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, The Colony Of The Slippermen, In The Cage, and Supper’s Ready – hardly ideal preparation for a two-hour marathon of early-day material. Onstage at a deserted Odeon, Mike Rutherford discovered that he’d forgotten an entire four-minute section in the middle of The Musical Box.

“I got a call from management to go down to the Hammersmith Odeon to shoot the rehearsals,” says photographer Robert Ellis, who has worked with Genesis since 1972. “I was amazed because I didn’t know it was going to happen. I’d been on the tour with the band up until that time, in America and elsewhere, and I didn’t know anything about it. So I guess it was a last minute decision to hold these rehearsals… [but] it sounded under-rehearsed. There’s no question about that.”

The bill at the Bowl also included The Blues Band, John Martyn, and Talk Talk. Under gunmetal skies, the audience treated the latter group to a torrent of boos and bottles which suggested that fans of progressive rock were not without a regressive edge. Six years later, Talk Talk released Spirit Of Eden, an album of such grand invention that it made Genesis sound like The Wombles.

The name Six Of The Best encompassed Peter Gabriel, the three full-time members of Genesis – a line-up completed by keyboardist Tony Banks – as well drummer Chester Thompson and guitarist and bassist Daryl Stuermer, the band’s additional touring musicians. The nom de guerre also gave a knowing nod to kind of corporal punishment once meted out at Charterhouse, the private school in Surrey at which most of its members first met.

Backstage at the Bowl, Gabriel sat in his dressing room like a nervous schoolboy. “Peter wasn’t at all confident about the whole thing,” Ellis remembers. “[In fact] I would characterise him as quaking in his boots.” At his keyboards, Tony Banks wore a tracksuit on which was written the word “kamikaze”, an adjective that “underlined [his] attitude to the whole night.”

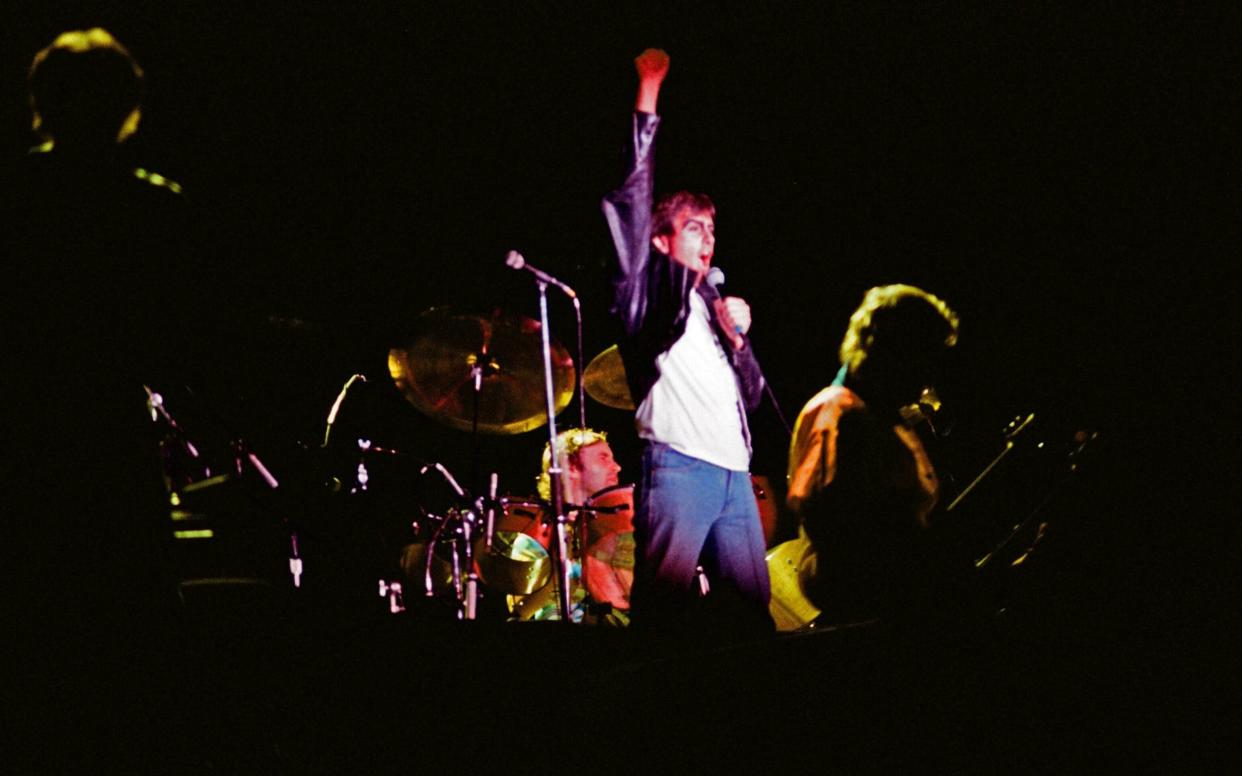

The sense that Genesis were flying by the seat of their britches was further emphasised by the arrival onstage of Peter Gabriel. With the musicians in place, the singer was brought out inside a coffin perched on the shoulders of four pallbearers. His entrance was as much of a surprise to the band as it was to 60,000 rain-soaked supporters. It had been seven years since Gabriel bid goodbye to democracy, and he wasn’t about to embrace it again now.

“We all smiled when the coffin came on,” recalled Mike Rutherford. “It was, like, ‘That’s our Pete.’”

Gabriel would later wryly describe his unconventional appearance as “a typically humble gesture.” Back from the dead, the singer emerged wearing the kind of leather jacket adorned by Rael, the half-Puerto Rican New York adolescent whose story is told in the confusingly conceptual The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway album. Taking their cues from their most widely-discussed release, the group kicked off the night with Back In N.Y.C.

“We were very under-rehearsed because we only spent a couple of afternoons working at it,” said Phil Collins. “But I guess it must have fallen back into place quite easily, otherwise we would have been in trouble.”

But this was no scratch-band comprised of have-a-go heroes onstage in a blues bar in Beckenham. This was a union of consummate and supple musicians capable of steering their way through the complexities of Firth Of Fifth as if it were no more complicated than Blitzkrieg Bop.

Robert Ellis disagrees. “It was a terrible show,” he says. “An awful show. They pulled it off only because they wanted to, but in terms of a performance it was hardly their finest hour. There are a couple of bootlegs going around, and I wouldn’t urge anyone to go and listen to them because they’re really not very good. If you heard those bootlegs you’d be forced to agree with what I’m saying.”

For decades, Six Of The Best at the Bowl was the Holy Grail of counterfeit collections. Scratchily recorded by a member of the audience, the two-disc set buttresses the evening in all its frantic glory. The determined sloppiness of Turn It On Again and Solsbury Hill – the evening’s two newer songs – and the paint-stripping abuse meted out to DJ Jonathan King, who introduced the group, suggest an occasion that bordered on the raucous.

Perhaps most impressive of all is the sound of a 60,000 strong all-male voice choir singing Happy Birthday to Mike Rutherford. From smoke-filled refectories to the slopes of adulthood, an audience as dedicated at this did not have to wait for the invention of the internet to discover, and remember, the date of birth of a perfect stranger.

“Some of you may be wondering what we’re doing here,” announced Gabriel from the stage. “But actually this is a sequence from a previous event by the name of Womad… a great event that lost a pile of money. But I’m very lucky to have a group of people [here] who support these ideals, so in return for your cash we’ll give you what we think you will like from this combination.”

“I can’t express well enough just how much the audience wanted this [concert] to happen,” says Robert Ellis. “They stood knee-deep in mud – and it really was <<very>> muddy – on a site that stank to high heaven. It was like being in some cow-field that had just been covered in manure. I felt awfully sorry for all the people that stood there for all that time.”

But for the bargain price of Immersion Foot Syndrome and the loss of no more than three or four toes, scores of thousands of people bore witness to the first and only reunion of Genesis in their early form. For the final two songs – I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe) and The Knife - Six Of The Best became seven when guitarist Steve Hackett, who left the group in 1977, emerged to an overwhelming ovation.

And that was that. Four years later, with the release of the So album, the critically adored Peter Gabriel became a global pop star every bit as famous as Phil Collins. Genesis motored on as recording artists until 1997.

While their detractors bemoaned a descent into “dad rock”, those with keener ears heard songs such as Dodo, Abacab, Mama, Home By The Sea, and Domino, and understood that weirdness still lurked beneath the group’s increasingly shiny exterior.

“Although they are often portrayed as very unhip, exploitative capitalist men of the rock world, it’s entirely down to them that the Womad movement can move, or struggle, or crawl forward,” said Peter Gabriel of the reunion show. “And they didn’t get anything out of it.”

Backstage at the Bowl, the re-united members of Genesis stood uneasily amid the champagne and cakes of the aftershow party, unsure as to how their evening had gone. But a night’s work in a new town in the south of England raised £1.2 million. The tally rescued Peter Gabriel from a future on the bones of his backside, and ensured the continued existence of an organisation he founded with the purest of intentions.

Robert Ellis’s book Genesis 5, a collection of rare Genesis photographs, is available now from The Rock Library