Sexy and subversive: tartan’s chequered history

At a Bronze Age burial site in north-western China 45 years ago, a group of archaeologists made a surprising discovery. Inside a humble mud-brick tomb, beneath a covering of reeds, they found the mummified remains of an almost 6ft-tall man, with a long, broad nose, a thick ginger beard, and spirals of red and yellow ochre painted on his cheeks.

In other words, he didn’t much look like a local, but if his features were unexpected, they were nothing compared to his clothing. Beneath a hefty, dark crimson tunic, he was wearing a pair of brightly coloured tartan trousers.

Growing up in Edinburgh in the 1980s and 1990s, tartan to me was just another part of the corny, cartoon version of Scotland the city sold to tourists, along with orange wigs, cuddly Highland cows and vaguely Anglophobic tea towels. It was what the hairy men in blue face paint wore while stomping up and down the Royal Mile with banners and leaflets in the years between the 1995 release of Braveheart and the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999. It was twee, parochial, even self-parodic – the stuff of shortbread tins and sofas in Highland hotels – and, at least for my teenage self, no source of national pride.

How wrong could I have been? As events since that wanderer’s arrival in China about 3,000 years ago have proved, tartan may be the best-travelled, most accepting and adaptable fabric on earth. And a forthcoming exhibition at the V&A Dundee aims to set the record straight by saluting its extraordinarily wide and persistent cultural reach.

Drawing together more than 300 pieces from everywhere from the Alexander McQueen archives to the Highland Folk Museum, the exhibition will explore tartan’s long and eventful existence: a chequered history in more ways than one. This is, after all, the same crisscross of colours that found a home in preppy midcentury American Ivy League style – and, barely a decade later, the snotty anarchy of British punk.

But then tartan – and specifically the kilt – has always been the most welcoming of national costumes. During my time at St Andrews University, when my own view of tartan decisively shifted, there was no hand-wringing over cultural appropriation as students from all racial and national backgrounds pulled on Highland dress for ceilidhs and balls. (A rented kilt can look dashing, and dare I say even sexy, in a way a rented suit never quite does.)

For my 18th birthday, I had one made up in Gunn Modern – a traditional dark blue and green pattern struck through with a line of blood red. For my wedding, I had a second, slightly wider one made in Gunn Muted, the colours of which are closer to the natural dyes of the classic Clanngvn tartan in the Vestiarium Scoticum – an 1842 reproduction of a 16th-century manuscript that detailed the official patterns of the old Scottish Highland and Lowland clans.

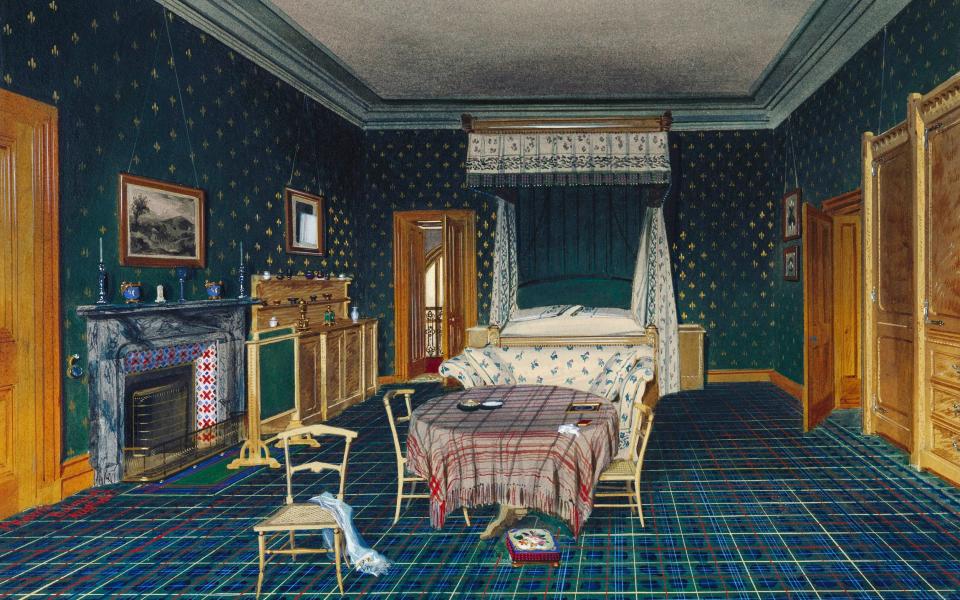

This was a hugely influential volume – as responsible for the Victorian mania for tartan as Prince Albert’s purchase of Balmoral Castle in 1852 and the surging popularity of Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley novels. But there was just one hitch: it was a load of old rubbish. The book was a forgery, and the self-styled “brothers” behind it, who claimed to be direct descendants of Bonnie Prince Charlie himself, are now believed by some to have been a homosexual couple from Surrey.

Yes, by then, Scots had been wearing tartan for at least two millennia, as had tribes from all over Europe and beyond. (The word itself is thought to have slipped into English in the mid-1400s via Old French: either from tiretaine, meaning a strong, coarse cloth, or tartarin, a fabric worn by the hardy Tartars, and much valued in medieval times.) But clans didn’t associate themselves with specific patterns until the 18th century – shortly before the wearing of tartan was outlawed by the British government after the Battle of Culloden, in the hope this would stave off any future uprisings.

That rebellious heritage was invoked by Vivienne Westwood when she dressed the Sex Pistols in the 1970s. Yet it’s striking how little traction tartan has with the current Scottish separatist movement. You’ll struggle to find a trace of it in any SNP publicity material, while pro-independence rallies are aflap only with saltires and the odd lion rampant. Is it possible that tartan’s mawkish reputation of 30 or 40 years ago – the backward-looking Brigadoon and Braveheart of it all – have helped spare it from contemporary politics?

If so, as a unionist quisling who’s lived in England for the past 20 years, I can only say I’m deeply grateful. To me, right now, tartan means celebration: bright and smart, it’s the original good-time textile. In fact, if you’ve ever been to a Scottish wedding – or, rather, heard a Scottish best man’s speech – you may be familiar with the story of Archie and Alec, two Glaswegians who were once overheard in the pub discussing the arrangements for Archie’s forthcoming marriage.

“It’s a’ set,” Archie says, beaming with pride. “I’ve booked the kirk, the flooers, the drinks, the motors – I’ve even got mysel’ a kilt to be married in.”

“Sounds great,” Alec says. “Whit’s the tartan?”

“Oh,” Archie replies, “I think she’ll just be in white.”

Tartan is at V&A Dundee (vam.ac.uk) from next Sat to Jan 14