Sexual Abuse in Modeling: The Outcry Grows

Could modeling — and fashion photography — be the next sector that’s put under the spotlight for sexual abuse?

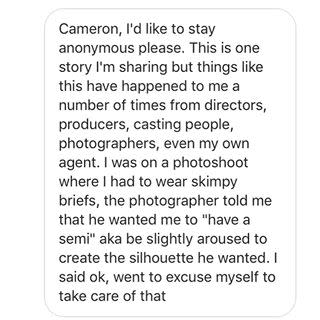

While rumors about abuse and sexual harassment of female and male models — and the photographers, agents and others who perpetrated it — have circulated within the fashion world for years, Cameron Russell, a well-known model, started posting stories from models on Instagram last week about abusive situations they’ve encountered — from sexual harassment and molestation to attempted rape. Hundreds of models have weighed in so far.

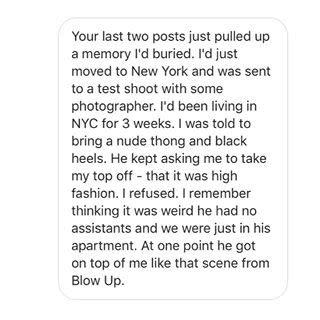

The anonymous comments posted on Russell’s Instagram describe a myriad of scenarios, with models describing photographers propositioning them, physically grabbing them, exposing themselves and sending nude photographs. There are also accounts of underage models unknowingly winding up in unchaperoned situations or being asked if they were a virgin.

Another commenter described how at the age of 17, midway through a normal shoot, she was “basically forced” to take her clothes off to get in the shower so the photographer could take photos and he took advantage of her in many ways.

Russell advised her 89,300 followers, “If you have been a victim of rape or assault 24/7 support is available from rainn.org,” referring to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

Executives at The Lions Model Management LLC, which represents the 30-year-old Russell, did not respond to a request for comment, nor did Russell.

“I think what Cameron is doing is very important. All models deserve the right to feel safe and respected. Unsafe environments should not be tolerated and abusers should be reported,” said Steven Kolb, chief executive officer of the Council of Fashion Designers of America.

“CFDA puts its support behind Cameron and others who are speaking out. I also applaud the Model Alliance and their efforts,” he continued. “We started the CFDA Health Initiative in 2007 to address eating disorders and underage models. In recent years we have encouraged more diversity on the runway as part of our fashion week outreach to the industry. I believe we’ve been able to impact positive change with our work. While we have not been specific on sexual harassment, our Health Initiative is committed to the notion of a healthy mind in a healthy body, and there cannot be one without the other. I do think it important that we expand our Health Imitative guidelines to be more specific on harassment and it is something we will do.”

When James Scully, a casting director, posted on Instagram in February allegations that models were being abused during a Balenciaga casting, it set off a firestorm. He said he received almost 10,000 responses in the first two hours about abuses models had endured in their careers.

He said he got e-mails from girls saying that a stylist touched her. “I discovered in speaking with other agents and other girls, I started to hear more stories like this.…It was in the air, and we knew it. I didn’t know the extent. Especially with these test photographers and those that kind of prey and take advantage of these girls. You always hear an isolated thing.…You hear the stories and I was getting stories about stylists and a couple of photographers,” he said. He said he would hear about sexual harassment and how a haircut destroyed a girl’s sense of self-esteem, and the agency dropped her.

“To get these e-mails from these boys and these girls is really devastating. Three days after it happened, I went home to 1,300 e-mails. From the girls and the boys and from their parents. The abuse overall is rampant, and the fact that it has become rampant is because it all became about power,” said Scully.

The reason people don’t speak out is because they’re afraid they’ll be blackballed, he contended. “That’s where the double standard is the worst,” said Scully.

This fall, Kering and LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton issued a charter to ensure the well-being of models. The charter, which has been implemented by both groups’ brands worldwide, requires models to present a recent medical certificate proving their overall health, and bans the hiring of models below the age of 16 in shows or shoots representing an adult, among other measures. Models ages 16 to 18 must have a chaperone or guardian on the set during the shoot.

François-Henri Pinault, chairman and chief executive officer of Kering, said at the time that the group had been working on the topic since 2015, but was moved to act quickly after Scully blew the whistle on several brands, including Balenciaga, Hermès and Elie Saab, for allegedly abusing models.

Concerning Russell’s Instagram with all the models’ stories, Scully said it was “incredibly brave” for the models to post their stories. “I think what she did is awe-inspiring [and] brave. She’s opened a door that was never opened,” said Scully, noting that many of the girls who weighed in were under 18.

Faith Kates, president of Next Model Management, said she personally doesn’t hear that much about abusive behavior, and when an abuse has occurred over the years, she would call the photographer directly. “I think Next is pretty powerful and the girls don’t get hit [on] that much anymore. I think the ones that do are the ones that don’t have great representation. We have a voice,” she insisted.

She recalled an incident that happened many years ago when someone was giving a girl drugs. “I went to the guy’s office with a bag of goodies that he was giving her and I said, ‘if you ever see me on the street, you should cross it.’ And if he ever did it again, I would put him in jail,” she said.

“I’ve made a lot of phone calls over the years,” she continued. She said she tells her girls: “If you think ever that somebody’s bothering you on the set, you call us and somebody will be there in 15 minutes. We do what we can do to protect our people,” she said.

Michael Gross, author of “Focus: The Secret, Sexy, Sometimes Sordid World of Fashion Photographers” and “Model: The Ugly Business of Beautiful Women,” addressed the abuse that has occurred in the modeling industry for years.

“I think that among the people who understand how the sausage gets made, there has always been an understanding that there are industries in which the bodies of attractive young men and women are treated as commodities. It has been a ‘below the surface of the ocean’ phenomena not for weeks or months or years but for decades,” he said. In his 1995 book “Model,” he called the industry “legalized flesh peddling, equating modeling agents as pimps.”

“Within the trade that [statement] wasn’t considered as a revelation….it’s because there’s a sense that that’s the way things are,” he added.

Addressing why the Harvey Weinstein scandal has blown up and the issue of abuse in the modeling industry has not despite copious examples over the years, he said, “Models are fungible. Models don’t get the respect that actors and actresses do. Because they are seen with no skill other than being born with lucky chromosomes, whereas people are attached to actors and actresses,” he said. “The public doesn’t care as much. Photographers do not have the kind of power that a movie mogul has.”

He suggested several reasons why sexual harassment stories from such industries as media, entertainment and modeling are coming out now. “A crack develops, instead of being patched, it opens wider. In fits and starts we have been moving toward a culture that is not tolerant of this behavior,” he said. “Despite the election of Donald Trump, it doesn’t mean that society isn’t more woke. It is two steps forward, two steps back,” he said.

Gross said he decided to open and close “Focus” on Terry Richardson, whose sexual abuse of models has been widely alleged. “It was made because I got on the phone with a lot of people who deal with fashion photographers on a daily basis.…I asked who matters most right now?…Not unanimously, but overwhelmingly it came down to Terry.”

Asked whether he believes the industry will change based on the outpouring of testimonials on Russell’s Instagram, he said, “I don’t think fashion can resist the tide of changing times because it’s fashion’s job to reflect the times.”

If more models come out and the industry pays attention and changes its culture, “maybe it [the response] won’t be, ‘clean that girl up and get her back on the set.’ Maybe it will be ‘get that photographer the f–k off the set.'”

Susan Scafidi, founder and director of the Fashion Law Institute at Fordham Law School, said, “Every model has a story of sexual harassment or abuse, whether her own experience or someone else’s. Perhaps that’s not surprising, given that the same is probably true of most professional women — and given that female models frequently start working especially young, with little supervision, and in a profession that focuses on their bodies. Most fashion professionals are just that — professional — but the very nature of the modeling industry can attract predators.

“Combating sexual abuse calls for a combination of louder voices, brighter light and better laws. The megaphone of social media can be effective in certain instances, in particular when either a serial harasser or a target of abuse has a recognized name or thousands of followers. Most of the time, however, the subject is a whisper in the shadows, inconsistent with the fantasy and glamour of the fashion industry. Models, like other victims of harassment or abuse, tend to be ashamed to speak or afraid of losing work. There’s always another young aspirant waiting in the wings.

“Legally, many models who experience sexual harassment have no recourse unless they are actually threatened or physically violated, in which case criminal law may apply, assuming enough evidence to bring a case. Since models are considered independent contractors, sexual harassment laws designed to protect employees typically do not apply. New York State’s inclusion of models under 18 in its child performer protection law starting in 2013 was a victory, but more legal support is necessary. In fact, in an era when traditional employer-employee relationships are giving way to the gig economy more generally, society as a whole could benefit from studying the problems experienced by models and creating structures to combat sexual harassment and abuse in every context,” said Scafidi.

As for the timing of these abuses coming to light, she said, “Why now? The political disappointment of many women has given rise to a trend toward female empowerment, amplified by social media, which enables the aggregation of stories and joining of voices. Ideally this will translate to structural change, not just the dismissal of a handful of marquee male predators, but there’s more work to be done.”

At work on the second season of “Food Quest,” Kim Alexis recalled her modeling days and some of the trouble she had at that time, mostly with photographers. “I had to set a healthy boundary right away. Harassment is when you set the boundary and they don’t respect it anyway,” she said. “They would make it very apparent that it would be fun to go in the next room and roll in the hay. Verbal comments I would get a lot. But when they were trying to get you to go to bed with them, I knew that that was abuse. That was a ‘No.’

“That’s what makes women get that tough exterior sometimes. You have to walk around like, ‘Don’t mess with me…’ It’s tough because in the business, people have access to your body, your makeup and your hair. People are touching you all the time. You yourself at 18 have to decide this is inappropriate, or the wrong time, wrong person or wrong comment,” Alexis said. “Now I’m not sure that parents are teaching young models where their boundaries are and what’s appropriate and what’s not.”

Referring to the Weinstein controversy, a former casting agent and magazine editor, who requested anonymity, said, “It’s the same in fashion — some really powerful people know things, but they’re not going to jeopardize their career or reputations to speak out about it. It took a Rose McGowan to stir the whole conversation. Harvey Weinstein wasn’t just a predator — he was a bully. There are a lot of bullies in our industry. I know that people get silenced because I have experienced that. There is kind of this cabal in our industry who know exactly what’s going on, but will never say anything. Anywhere there is powerful people, beautiful things, ‘creative’ minds, you’re going to have crazy, abusive behavior.”

Further complicating the situation is the hiring of teenage models. “We need to look at why we’re using models who are 14, 15, 16 in advertising for big brands that a 14, 15, 16-year-old could never afford to buy? I just looked at the shows again and there are girls who are really young — 16. Why are we perpetuating these images of these young girls as women?” the former agent said. “If you read Cameron’s Instagram, there are girls who had experiences when they were 15, 16 because they were sent on casting calls and go-sees. The mom might be in the other room, but they are having a bad experience with some photographer. Maybe we have to say girls need to be 18 or older to start modeling.”

Bethann Hardison, who ran her own agency at one time, said no agency would send a girl out knowing she could be in a situation she could be compromised. That was even more so the case in the Eighties. “With Eileen Ford, it was don’t f–k around. Wilhelmina [Cooper], Zoli [Zoltan Rendessy] — they were hard-core,” she said. “But I know that boys have been told, ‘Do what you have to do to get the job.’ With boys, there’s less care with them.”

While she allowed that ”surely” girls have faced incidents, Hardison said the problem of harassment leans more toward photographers and casting directors than fashion designers. Strict as an agent, Hardison said she believed that models seen out at night never got booked during the day. “That was my philosophy, so you make your choices. I was so strict. I didn’t hang out with people where we had to do drugs with my clients and stuff like that. My agency was a whole other style,” she said. “There’s no doubt girls were compromised in the Eighties and Nineties for sure. But I’ve never had anyone who I represented tell me that happened to them. But I’ve talked to boys who have said sometimes things were expected. They could be compromised for sexual advances.”

Former “America’s Next Top Model” judge Kelly Cutrone said she has never witnessed anything on set, but stressed the importance of women speaking up for themselves. “There is a lot of fine-line stuff. If a designer wants somebody to wear a sheer blouse, it’s part of the job. You have to speak up for yourself or you’re going to be expected to do certain things that could be seen as marginal. They’re selling illusion and sex a lot.”

Speaking in general terms, not specific to the fashion industry, Cutrone said, “There are plenty of women who have gone to work and it’s been made very clear that if you make yourself sexually available, you’re going to get extra things. Or they have gone to work and been physically exposed or visually raped,” she said. “…On one hand, you want to say, ‘If you’re tall enough to be a model, be careful because there are people looming who are sexually inappropriate and they’re predators.’ But guess what? They’re in the hospital, the fire department, the accounting department, in the courts — wherever there is male culture there are sexual predators. They come in all different shapes and sizes and they work in all different places. They do not discriminate based on race, ethnicity or economics. That is a really huge issue.”

Cutrone said what she finds most troubling is the online responses of women who said they didn’t know what to do. So much so that she is considering starting an online community with a group to teach women about sexual harassment. “If women are in a situation where their boss is asking them to watch them shower and they don’t know what to do.…they don’t have the confidence of their voice or whatever — there is a huge problem here. It’s the same problem my daughter is going to have if she goes to a rock concert and she is not prepared for a terrorist act or a shootout. Women really need to be taught the seriousness of it and it happens every single day — everywhere.”

Former model Jennifer Sky is at work on a memoir about her three years of modeling in New York and abroad in the Nineties. Recalling her modeling days between the ages of 14 and 17, she said, “I was physically assaulted. Not only was I belittled by men and women on fashion sets, I was made to feel like just a prop. The thing is, maybe actors sign up for that. You sign up for a job that’s tough and you’re getting paid a certain amount, but these are little kids.…The adults on the set should have been looking at us as children and thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, we can’t let this photographer talk to that little girl like that.’”

She argued that the look that many designers present is the same one that couture houses put forward in the Thirties. “Just in the few past years, we’re seeing people of color on the runways and other body types,” Sky said. “I was able to see the difference between a workplace that was unionized and one that wasn’t because at 15 I also became an actor. The way I was treated on sets that were overseen by SAG were completely different. The fight that we are having now [is like] the one that actors had against the studios in the Thirties. When I returned to New York to finish my education at 30, the fashion industry hadn’t innovated. The same archetype was on the runway — these very young, thin, teenage white women,” she said. “The one change that would make the biggest difference would be if they made a requirement that 18 [became the required age] to model.”

Suzanne Lanza, a model whose career spans 30 years, recently posted, “When was your first experience of sexual harassment? What happened?” Reached Monday, Lanza said, “There are all these people saying that it’s not an issue in the fashion industry. That’s a total joke. I don’t know anyone who I know personally who hasn’t had some form of harassment in the fashion business.”

Recalling her first modeling trip to Europe as a high schooler, Lanza was taken by her agents one afternoon to go swimming at a house in Italy. “Fortunately, I had my own bathing suit, which was like a turtleneck one-piece. But some of the other girls didn’t. They said, ‘Oh, we have bathing suits.’ But somehow they only had bottoms and no tops. Things like that were presented as really normal. I was 18, but there were a lot of 14-year-olds,” Lanza said. “And I was made fun of. I also remember walking off a job because they wanted me to take my top off. They called my agent and tried to intimidate me.”

Having modeled for 30 years since her first major job with Herb Ritts, Lanza said, “Everybody knew there are ‘The Playboys’ — these predators and I’m sure a lot of the agents were complicit, too, bringing young girls to these villas to go swimming, not protecting them in a way they should have.’”

As naïve as she was as a teenager, Lanza said she knew enough not to go anywhere alone. Depending on their work schedule and financial needs, some models may need a free meal or job prospect so they will run with similar crowds or go out at night (to events organized by club promoters.)

“God bless Eileen Ford. She was known for being so strict — for a reason. Hearing that tape of Harvey Weinstein [with model Ambra Battilana, who wore a wiretap for the New York Police Department to try to catch Weinstein, but charges never materialized], that’s the way that they are. They try to make you feel bad about it, and you’re not the cool one if you don’t do what they want you to do. It really affected me so much hearing that,” Lanza said. “Even women asked, ‘Well, why was she in that situation?’ Why shouldn’t you be able to go to a hotel room with a man and then say ‘no’? We need to not judge women.”

Related stories

What Does Gucci's Anti-Fur Policy Mean for the Industry?

Europe's Major Markets Edge Down in Early Afternoon Trading

Europe's Major Markets Seesaw in Early Afternoon Trading

Get more from WWD: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter