Sepp Kuss Is Chasing a Historic Win. His Hometown Is Going Bananas.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared on Outside

A few dozen people milled about the Mountain Bike Specialists bike shop in downtown Durango, Colorado on the morning of Friday, September 8. The store had opened two hours earlier than normal, and employees set out free donuts, bagels, and coffee. Guests munched on breakfast as they chatted about the topic du jour: local cyclist Sepp Kuss, who was leading Spain's Vuelta a Espana.

Around 8 A.M. someone flicked on the television showing a livestream of the Vuelta's 13th stage. An hour or so later, the broadcast showed Kuss, clad in the red race leader's jersey, accelerating away from the peloton on the slopes of the famed Pyrenean climb, the Col du Tourmalet.

"People literally roared, it was really exciting," Michael Philips, a salesman and bike fit specialist at the shop, said. Phillips, 60, helped organize the watch party to honor Kuss, who was sponsored by the shop when he was a teenager. "You can tell there's a real heartfelt desire in town for him to win," he added.

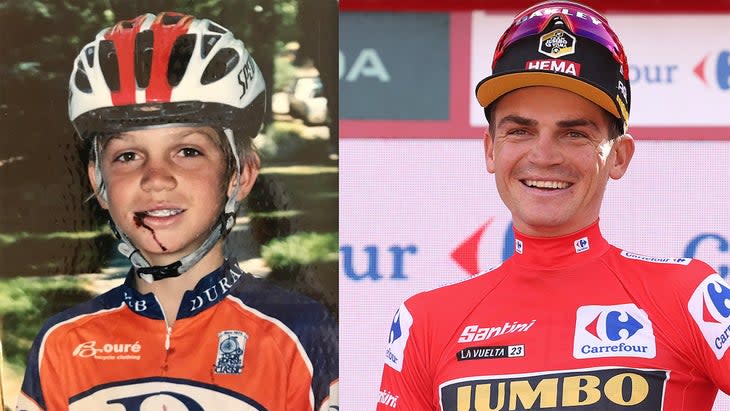

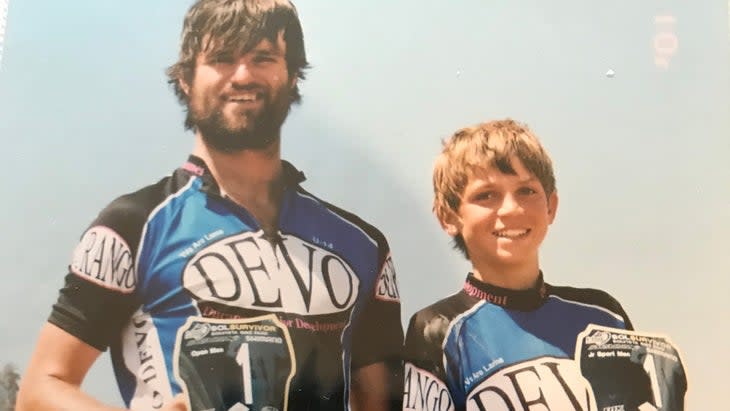

To stroll the streets of Durango these days, locals tell me, is to witness a cycling-crazed community unify behind its hometown hero. Kuss grew up in Durango, the son of Sabina Kuss and Dolph Kuss--the latter is a stalwart in the Colorado ski industry and a former coach of the U.S. Olympic skiing team. As a teenager Kuss joined the Durango DEVO mountain-bike program, and became a nationally-ranked racer. Then, in his early twenties, Kuss exploded onto international road cycling scene, making the jump to the European WorldTour at age 23. A few years ago he relocated from Durango to a village in the principality of Andorra in the Pyrenees, where he can train on the same roads used in the Tour de France.

Durangoans have not forgotten Kuss in his absence, and his popularity has reached a peak amid his success at the Vuelta. Kuss posters hang in storefront windows. Kuss cartoon stickers stare out at the world from lamp posts and from the backs of laptop computers. Framed photos of him as a teenaged cyclist adorn the walls of bike shops. When a group of cyclists spins by, you know who they're chatting about.

"He's the talk of the town," says Todd Wells, a three-time Olympic mountain biker who now works as a mortgage lender. "It's all anybody is asking about on the group rides. Do you think he can do it? Do you think he can hold on to the lead?”

That's because Kuss, 29, stands on the precipice of making American cycling history. After Thursday's 18th (of 21) stages, he leads the Vuelta by just 17 seconds over his Jumbo-Visma teammate, Jonas Vingegaard of Denmark. Should Kuss maintain his advantage through Sunday's final stage in Madrid, he will become the second American to win the Vuelta, and just the fourth American male to claim one of pro cycling's three-week grand tours. That tiny circle includes Greg LeMond, who won the Tour de France in 1986, 89, and 90; Andrew Hampsten, who won the Giro d'Italia in 1988; and Chris Horner, who claimed the 2013 Vuelta.

The historical significance is not lost on Durango residents. The small city in southwestern Colorado is a hotbed of American cycling, and over the years it has been home to world champions and Olympians: Ned Overend, John Tomac, Ruthie Matthes, Julie Furtado, Travis Brown, among others. In Durango, cycling regularly makes front-page news and connects with general sports fans, and not just those who don Lycra shorts and pedal along the paths and trails.

John Livingston, a public relations officer with the Colorado Department of Parks and Wildlife, told me some of his coworkers have asked him to avoid sharing the results of each day's stage--the Vuelta airs each morning--so they can watch the replay at night and be surprised. And when he walks around town, Livingston hears Sepp chatter almost everywhere he goes. I phoned Livingston to give me a temperature check on Kuss's popularity, because he has deep historical background on the topic. Prior to joining the state government he was the sports editor at the local Durango Herald.

"If I'm in a coffee shop or at the local distillery, people will come ask me for an update on the race--what's going on with Sepp?” Livingston told me. "He's become one of the biggest athletes in town."

When Kuss won a stage of the 2021 Tour de France, I asked Livingston to write about the victory's impact on the Durango community for VeloNews. That win, Livingston wrote, transformed Kuss into a Durango folk hero almost overnight.

Livingston told me there's a different vibe amongst Durango locals this time around. Back in 2021 people were surprised and elated by Kuss's stage win. Now, Livingston says, locals share a heightened level of anxiety watching Kuss defend his overall lead. Kuss has never raced for overall victory in a grand tour. History is at stake. His grip on the race lead is tenuous. Every day presents a new opportunity for him to lose.

"I think a year ago we would have been stoked to see him wear a race leader's jersey for a day or two," Livingston says. "Now we're more interested in seeing what it's going to take for him to win. I know I'm nervous."

The level of anxiety has been heightened by an unorthodox rivalry at this year's Vuelta: Kuss has had to fight off his own two teammates, who have tried again and again to wrestle the lead away. The inter-squad rivalry has generated a glut of controversy within the global bike racing scene, since teammates traditionally try to help one another win big races.

Kuss entered the race as a domestique, a worker-bee for Vingegaard, the reigning Tour de France winner, and Primoz Roglic, winner of the 2023 Giro d'Italia. But he took over the race lead on stage 8, placing him in a somewhat awkward situation. For the last four seasons Kuss has helped both Vingegaard and Roglic score huge victories on the international stage, sacrificing his own ambitions to vault them to victory. They are the team's star riders, while he is the helper. But when Kuss took over the lead, his two teammates appeared less than enthused to help him win.

Vingegaard attacked Kuss on stage 13 to win atop the Tourmalet and bolt into contention for the race lead; the Dane did it again on stage 16 to bring himself within two minutes of the lead. On Wednesday's stage 17 Roglic and Vingegaard both dropped Kuss on the slopes of the steep Alto de l'Angliru, leaving the American to ride the final kilometer to the finish alone. But Kuss dug deep and limited his time losses to his own teammates, preserving his razor-thin gap to Vingegaard in the overall.

The tactics didn't sit well with cycling pundits, or with fans back home in Durango.

"His own teammates worked him over--it's pretty lame to see that happen," Wells said. "But Sepp keeps hanging on. You couldn't make the race more exciting if you tried."

Wells says the ugly battle has shown the world what Durango natives have know forever about Kuss's character. Long before Kuss entered the WorldTour, he was known in the Durango scene for his happy-go-lucky attitude. Bike racing is a stressful sport, where athletes agonize over diet, training, and results. The Durango DEVO program that Kuss grew up in preaches fun and camaraderie over cutthroat competition. The attitude, it seems, has stayed with Kuss to the highest echelon of the sport.

"You watch these road races and nobody is smiling at the top of these climbs, everybody is so serious," Wells says. "And then they show Sepp and he's grinning. He's so stoked."

Chad Cheeney, founder of the Durango DEVO program, says some of Kuss's laid-back attitude can be traced to his program, as well as to Durango's other top cyclists. Kids in Durango grow up riding alongside stars of the sport, and as a teenager Kuss regularly pedaled alongside Wells, Overend, and other renowned cyclists on the local group ride. Cheeney invited these men and women to attend DEVO practices and to share their experiences with up-and-coming racers like Kuss.

But a lot of the chill vibe, Cheeney says, springs from Kuss's own personality. Even as a kid, Cheeney says, Kuss valued fun over everything else in cycling. "People always ask me if I knew he was going to be this good when he was a kid," Cheeney says. "I tell them no way."

Shredding down trails was just as important as working the climbs, Cheeney remembers. And Kuss thumbed his nose at the sport's traditional rules around nutrition. "Sepp's favorite thing was pounding hamburgers after a race--or he'd crush Taco Bell before a race," Cheeney says. "Even back then people would be making fun of him for eating garbage food. He would just grin."

After Kuss won stage 6 of the 2023 Vuelta, he was handed the celebratory bottle of champagne to spray at the crowd. Many cyclists pop the bubbly, take a sip, and then hand the bottle down. Kuss, however, took a mighty swig, chugging champagne for several seconds before erupting with a mighty burp. The display of joy was not lost on Cheeney.

"Sepp looks like he's having so much fun," Cheeney says. "He's not your typical stone-faced winner."

Sepp Kuss, you legend! #LaVuelta23 pic.twitter.com/Kd8yvzWv6J

— NBC Sports Cycling (@NBCSCycling) August 31, 2023

This past July I phoned up Kuss on the eve of the Tour de France to talk about Jumbo-Visma's goals for the race, and how he fit into that strategy. After some talk of pelotons and echelons, Kuss brought up a topic he wanted to talk about: Durango. He told me he missed his hometown, and the people, the Mexican food, and trails. These days he returns home perhaps once a year to see family and friends before returning to Andorra.

Kuss told me his experiences in town had shaped his perspective, specifically on how he saw himself as a star athlete in an international sport.

"Being on a big team in the WorldTour, there are fans who look at you like a famous person, but I feel like I'm a cyclist just like you are," he told me. "That comes from the environment I grew up in. In Durango you're surrounded by the big stars, but I never thought about them that way. They're just the guys from the local ride."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.