Selfies Are Not the Enemy. Who Loses When Vanity Is Stigmatized?

The camera roll on my phone follows a rather predictable pattern: There are whole gridded chunks of near-identical portraits of my face and body from every discernible angle, followed by a hodgepodge of random screenshots, various objects and scenery, and then another hefty grid of near-identical selfies, and so on and so forth.

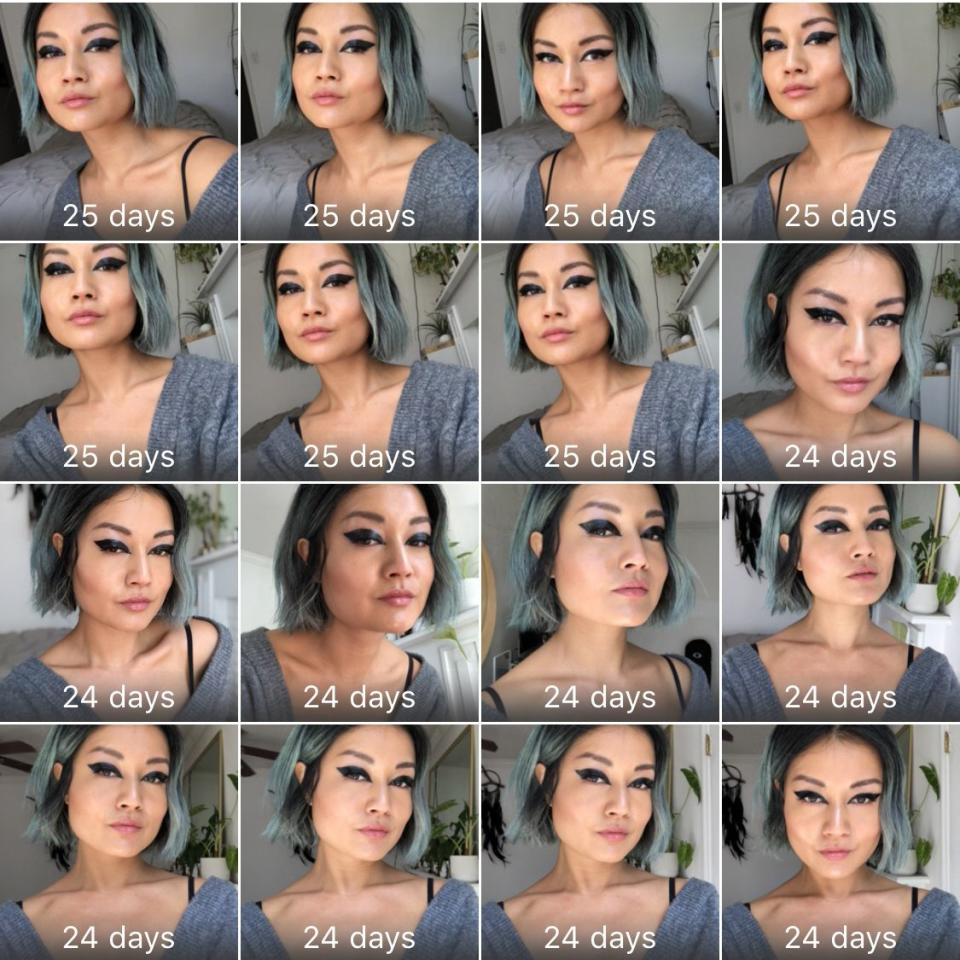

The average number of shots for one posted selfie hovers around the upper sixties or seventies, under optimal conditions (good lighting, good setting, good makeup/hair, etc). That number creeps past 100 when any of those things are compromised. This is not something that particularly irks me, but if someone were to scroll through this camera roll, I’d instinctually smack my iPhone X out of their hands, should they see the grid populated by upward of 100 selfies in a row. I’d rather someone find my nudes than witness “my process.”

Taking selfies doesn’t hurt anyone, isn’t offensive by nature, and is largely inconsequential. Somehow, though, selfies have come to define the smartphone generation's self-absorption. Some selfies are posted in earnest, some are posted in irony, and some take a stance against selfies altogether. Selfies are a public reflection — kind of like looking in a mirror and checking yourself out, but outwardly. It’s a technological reaping of natural human vanity in all its forms and iterations.

It's not exactly a secret that humans have been fascinated by appearances and concepts of beauty since the beginning of time. Most of the fairy tales I was fed as a kid involved wicked stepmothers who were homicidally obsessed with their looks and ultimately vanquished by their way younger and naturally beautiful stepdaughters (the "lesson" being that the fairest of them all wins because of some bogus ethical implication that beautiful people are morally good and vain people are evil).

No one benefits from liking themselves on someone else’s terms, and vanity is, above all, an extremely personal thing.

Go to any art museum and there are scores of paintings and sculptures of our centuries-old study of the human form. Psychological studies have discerned time and again the benefits of looking attractive — pretty people get ahead more easily in life, and looks are important, no matter how you feel about them.

What makes that tricky is that vanity, old as it is, has generally been viewed as vacuous, vapid, and contemptuous — a bit ironic when you consider how it's only been recently (like, post-millennium) that beauty conventions have shifted from prescriptive to expressive. No one appreciated being told how to look beautiful before then, and no one seems to appreciate how people broadcast their own beauty now. (One resolution: Minding your own business makes either a nonissue.)

Social media is the easiest target because it's the most fertile petri dish for vanity. Photo filters and those "Instagram aesthetics" have swung beauty standards into the realm of quantifiable validation with likes, comments, and followers. Maybe it’s the unabashed thirst for validation (and the disappointment in its absence) or the indulgence of self-performance that gets tongues clucking, but since when did liking yourself become so contemptible? We encourage people to be confident and to respect themselves, but to remain humble by murky standards. No one benefits from liking themselves on someone else’s terms, and vanity is, above all, an extremely personal thing — and it isn't always so appreciative of what one sees in their reflection.

Without visible vanity, in all its unmade, in-between, and self-examining stages, how can you expect beauty to be authentically dissected and decided?

Sure, our digital feeds are thoroughly oversaturated, and eyes may glaze over, blinded by blue light, but the cool thing about the democratized platform of handheld vanity is that there's no longer one authority acting as gatekeeper for what you get to see as beauty. My adolescence crested just when the Internet was becoming an in-home staple in my community. I didn’t have a cell phone until college (and it was a flip phone). My only visual cues for beauty came from magazines, which I devoured eagerly. And I didn't see anyone who looked like me in that celebrated context.

If I had had Instagram, Tumblr, or even Reddit back then, and saw people being themselves who looked like me, or just people who looked like anyone other than models in a magazine (read: thin and white), my attitude towards beauty — including a feeble and guilt-ridden resentment of those who fit seamlessly into those beauty molds — would've been so much more expansive.

Without visible vanity, in all its unmade, in-between, and self-examining stages, how can you expect beauty to be authentically dissected and decided? It's like your math teacher asking you to show the work on a test — tedious but enlightening. We're all subjects in a constantly evolving definition of what beauty is and what the bounds of beauty could be.

Selfie stigma existed before selfies did. It's the same stigma that makes assumptions about how much you should care about your appearance, and denial of the amount of effort and thought that goes into it. As icky as it may feel to be exposed in however many shots it takes to perfect a selfie, or how many filters you put on it, there's value in that "research" because understanding the neurosis of your own vanity, private as it may be, is still a way to connect with others, who in their own reflections may be looking to see someone who looks like them, someone like you.

Beauty isn't always pretty, but it isn't always supposed to be:

Pretty Privilege Is Something We Don't Talk About But We Should

Living in My Skin: 8 People Reveal Why They Love Their Freckles, Moles, and More

Navigating Beauty Standards as a Trans Woman Is an Impossible Balancing Act

Five women on body acceptance and self-love: