The Selfie Is Not the Only Contemporary Feminist Art Form

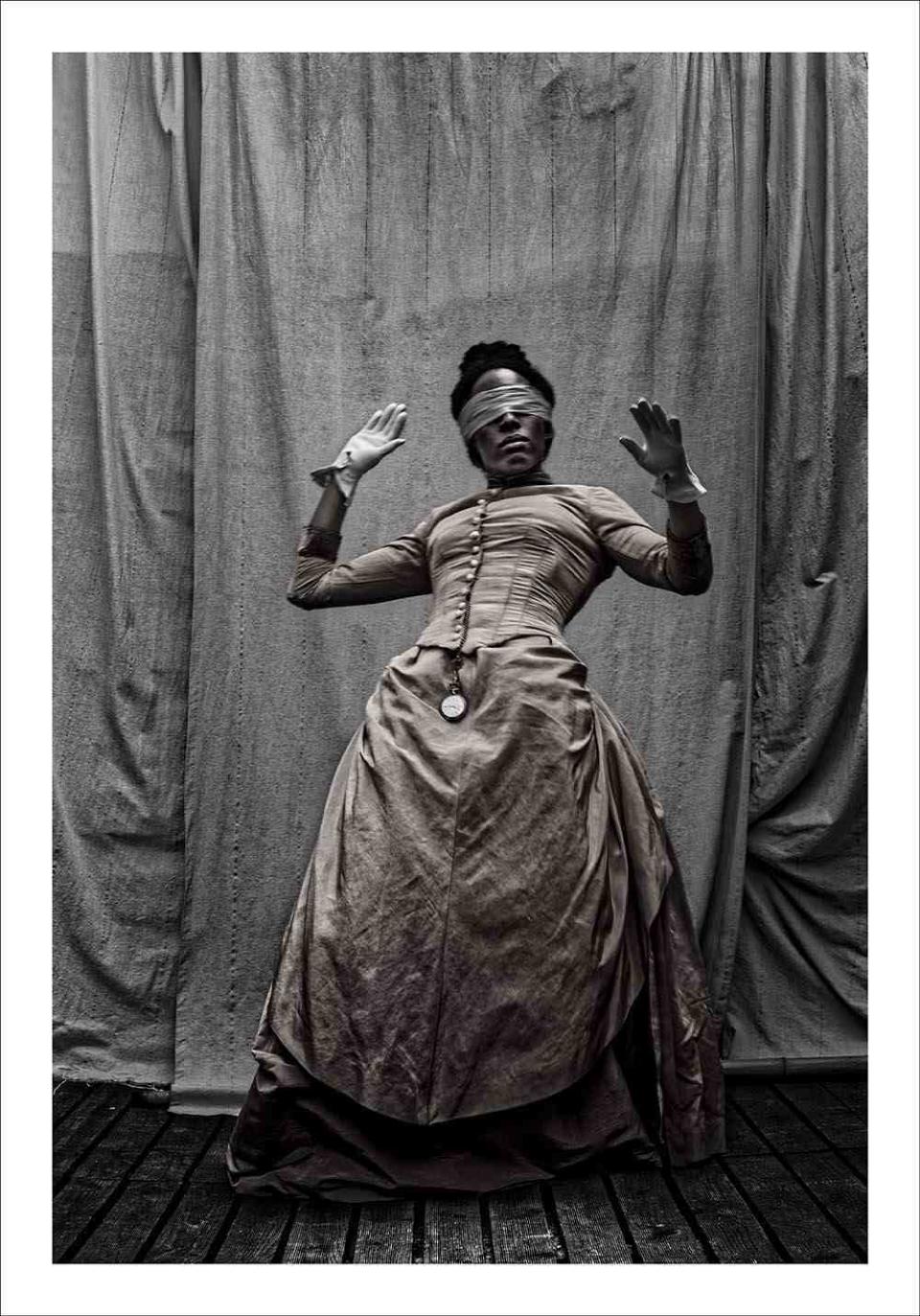

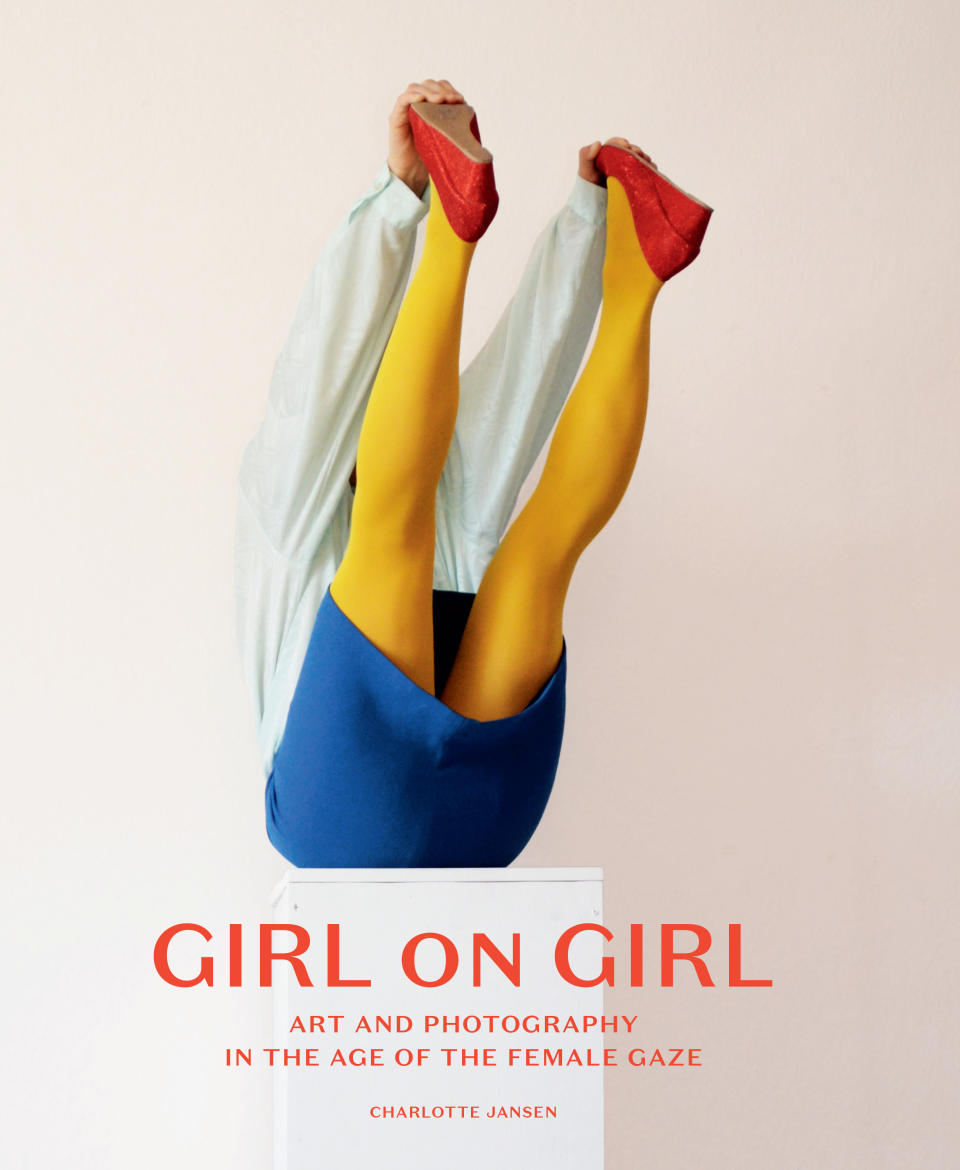

Charlotte Jansen is just fine with objectification. "We are always going to have beautiful pictures of women, and objectify women, and that's ok," the editor of the new photo book Girl on Girl, told ELLE.com recently. "But it's important that women have the freedom to create these kinds of images, too. Men have been doing it for centuries and haven't had to explain themselves!" In her sweeping new book, which looks at photographers from all ages from across the globe, Jansen explores the relatively unexamined explosion of female photographers who are turning their lenses on other women.

The result is a startling and stunning book that offers a rich, varied alternative to the idea of the selfie as the contemporary feminist art form. The story, as Jansen's book shows, is far more varied, and arresting, than that.

How did you come up with the idea for the project?

I'm inspired by the work of female photographers over the last five to ten years focused on female subjects. But I was also motivated by the lack of proper engagement with the work they were making. A lot of media attention on this subject was superficial, and framed all the work of women in the same way. Buzzwords like "selfie" and even "feminism" are kind of applied slapdash to everything without considering what that means. Women don't only produce work to describe femininity or to go against men or the patriarchy!

I was also really interested in how the public reacts to pictures of women. We encounter so many photos of women every day in lots of contexts, but we usually only understand them as either narcissistic (if the woman took it), as advertising, or as porn. I think that affects the way we then see women in a very real way. It also tends to affirm the idea that what women do is only relevant to women, or otherwise it should appeal in some way to the male heteronormative gaze. I wanted to understand why women photograph women and to see what the wider implications and impact of photographs being made by women of women might be in our world at large.

Women don't only produce work to describe femininity or to go against men or the patriarchy!

Was there a photographer that you felt you "discovered" or one that you feel deserves much wider acclaim?

Yvonne Todd's work definitely deserves more attention on the international scene. She has been working since the 1990s in New Zealand and I don't think her importance and influence has been fully appreciated yet.

Avia Wyse and Yaeli Gabriely are two young photographers, working in Dresden (Germany) and Haifa (Israel) respectively, who are definitely ones to watch, they are both Internet-shy but incredibly talented.

Can you talk a little bit about the motivation behind collecting only images of women and by women?

There has been a huge surge in the number of professional women photographers in the last five years, and I think it's really important to understand how and why that has happened and how images women produce might-or might not-be different from the pictures men take of women. Of course, what men make of women has been well documented throughout art history, so I think it's women's time!

Was there anything you felt you learned in putting together these interviews about the relationship between photographer and subject when both are women? (As opposed to having a male artist and female subject, for instance.)

One thing that seemed pretty unanimous was that women feel very different in front of the camera when there is a woman behind it. They feel more complicit, more comfortable. Regardless of their sexuality, there's a special exchange that happens between women when they photograph each other.

On the other hand, a few photographers also told me they felt more responsible towards their female subjects and about having possession of images of other women. This is why a lot of women start to turn the lens on their own bodies instead, to alleviate that kind of guilt about representing someone else, having control over someone else's image.

You wrote in one interview that "I tell Marzella that I often feel bad about my own image after looking at her pictures." How did putting this book together affect your self image more broadly?

I think a lot about how images affect me and how they might affect other women especially in a time of constant self-surveillance and comparison. Photography feeds massively into that system and of course female photographers do, too.

Like many women, I have really struggled with how I look. Alexandra is a beautiful woman, and we're trained so see that as threatening. She's a model, but what she shows in her personal work is much deeper than just looking good and being praised for it.

We are always going to have beautiful pictures of women and objectify women and that's ok. But it's important that women have this freedom to create these kinds of images, too-men have been doing it for centuries and haven't had to explain themselves!

Did you sense a generational divide among the photographers between the ones who had grown up on social media and the ones who hadn't?

I was born in '85 and so I was probably the last generation to grow up without Internet. I am grateful for that, but it has a lot of creative power for anyone who wants to create their own narrative and circumnavigate the mainstream media. I was surprised to hear from artists who grew up on social media that it can be such a positive and empowering thing.

But you can't really see a generational split in the work [between those who grew up on social media and those who didn't]. I think it's because the kinds of photographs we are exposed to have remained consistent; they've just moved online. Women have the same things to work against. If anything, it's harder to be taken seriously now if you only do your work on social media.

Do you see this book as an aesthetic project or a political one? Or how do you summarize the intersection for yourself in thinking about this project?

It's both―because the women all have very different approaches. You can enjoy it and interpret it many ways. But I hope that it will bring up some new discussions and encourage people to feel differently when they look at photographs of women.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

You Might Also Like