See the scrapyards where cruise ships, cars and planes go to die

Vehicle cemeteries

AA/ABACA/PA

Ever wondered what happens to aircraft, locomotives, passenger liners and automobiles when they eventually reach the end of their working lives? Most of these vehicles live out their last days in scrapyards while they await recycling, or where they simply rust away. Check out these eye-opening places where modes of transportation go to die.

Mojave Air and Space Port, California, USA

Alan Wilson/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The once-mighty jumbo jet has now been phased out in favour of more fuel-efficient models. United, Delta, British Airways, Air France, KLM and Qantas have all retired their Boeing 747 fleets with many ending up at the Mojave Air and Space Port boneyard in California.

Mojave Air and Space Port, California, USA

Paul Harris/Getty

The culled jumbo jets will likely be recycled – up to 90% of a plane can be repurposed. The Mojave facility is one of the world's top destinations for retired aircraft. Like other boneyards around the globe, it boasts ideal environmental conditions.

Mojave Air and Space Port, California, USA

Kim Davies/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

These include an arid desert climate, high elevation, low pollution levels and alkaline soils, all of which inhibit rust and erosion. The boneyard stores thousands of commercial planes. These range from aircraft that are beyond any state of repair to planes that will eventually be returned to active service, such as Qantas' fleet of Airbus A380s, which were returned to the airline after three years in storage.

Mojave Air and Space Port, California, USA

Todd Lappin/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Storage works out at around £6,100 ($8k) per aircraft, per month, so the costs to airlines can mount up considerably. In addition to planes manufactured by the likes of Boeing and Airbus, the boneyard stores a variety of aircraft including McDonnell Douglas and Lockheed Martin planes.

Mojave Air and Space Port, California, USA

Eric Salard/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

If you're keen to visit, the boneyard isn't actually open to the general public per se, but does put on monthly 'Plane Crazy Saturdays' during which enthusiasts can tour the now bulging facility and find out more about its activities. Admission is free.

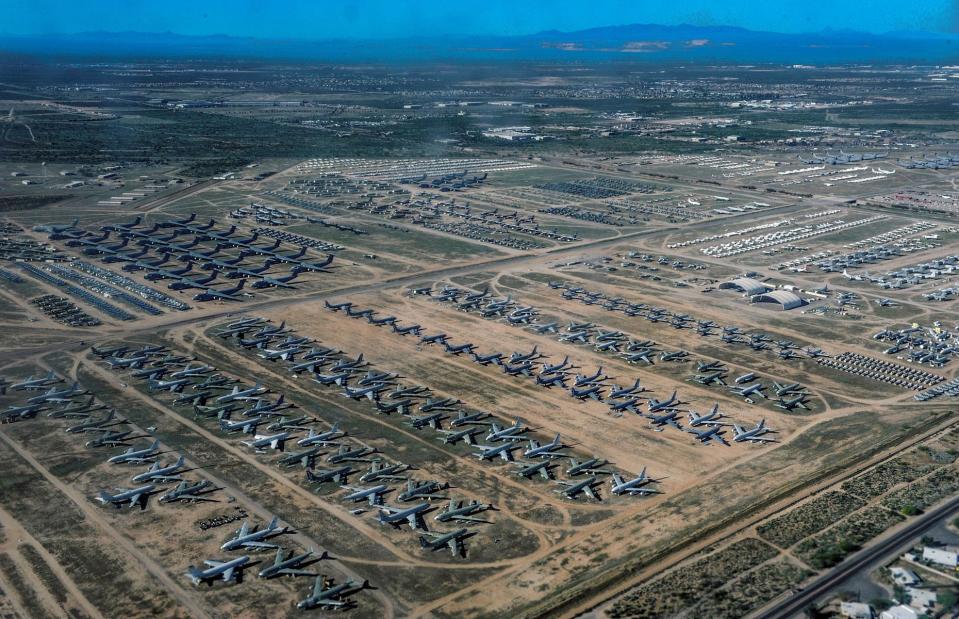

Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, USA

Stuart Rankin/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The largest aircraft storage and preservation facility in the world, the boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in the Arizona desert boasts thousands of decommissioned US military and government aircraft.

Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, USA

Airman Magazine/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG), to give the boneyard its official name, was set up after the Second World War and is now the only repository of decommissioned military and government aircraft in the country.

Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, USA

SearchNet Media/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Like the Mojave Air and Space Port, the location was chosen for its bone-dry desert climate, alkaline soil and elevation. The super-low humidity, non-acidic desert earth and high altitude help preserve the aircraft and prevent rust from forming.

Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, USA

Travelview/Shutterstock

A team of around 700 workers take care of the aircraft, which include a former Air Force One. The base is used for both short and long-term storage, and for salvaging usable parts from aircraft. In total, the boneyard returns hundreds of millions of dollars-worth of spare parts to military, government and allied clients.

Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, USA

SearchNet Media/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The boneyard has featured in a number of TV shows and movies, including the Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen. While the base is out of bounds to the general public, the adjacent Pima Air & Space Museum is a fascinating place to learn about aircraft old and new.

Teruel Airport, Teruel, Spain

Rab Lawrence/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Europe's premier boneyard, Teruel Airport, which is located in the remote Spanish province of the same name, was specially built to store and recycle spent aircraft. The airport also operates as a maintenance and servicing facility.

Teruel Airport, Teruel, Spain

David Ramos/Getty

Environment-wise, the Teruel boneyard – like its counterparts in California and Arizona – ticks all the boxes. The facility enjoys tinder-dry weather for much of the year, is situated at a high altitude and records very low pollution levels, which make for the perfect conditions to store and recycle aircraft. Aircraft are dismantled and recycled using the latest techniques.

Teruel Airport, Teruel, Spain

David Ramos/Getty

In terms of capacity, the airport can handle 250 large planes at any one time. While significantly smaller than the Mojave Air and Space Port and Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, the boneyard is no doubt doing a roaring trade as new technology renders older planes obsolete.

Teruel Airport, Teruel, Spain

David Ramos/Getty

The Teruel facility stores and dismantles planes manufactured by Airbus, Boeing, Bombardier and other leading names in the global aviation industry.

Asia Pacific Aircraft Storage, Northern Territory, Australia

Steve Strike/Getty

Down under, Asia Pacific Aircraft Storage at Alice Springs Airport in Australia's Northern Territory is the leading place where planes go to die. The world's newest boneyard, the facility was completed in 2013 and became operational the following year.

Asia Pacific Aircraft Storage, Northern Territory, Australia

Steve Strike/Getty

Again, the site was chosen thanks to its optimum conditions which minimise rust and erosion – the Alice Springs climate is extremely arid while air pollution is exceedingly low. The boneyard covers a total of one hundred hectares.

Asia Pacific Aircraft Storage, Northern Territory, Australia

Steve Strike/Getty

Although Australia's national carrier Qantas has for reasons unknown opted to store its planes at the Mojave Desert facility in California, the Alice Springs boneyard has no shortage of clients.

Asia Pacific Aircraft Storage, Northern Territory, Australia

Steve Strike/Getty

The facility's leading customers are airlines based in the Asia-Pacific region and have included Fiji Airways and Singapore Airlines. During the coronavirus pandemic, Singapore Airlines stored six of its Airbus A380 super jumbo jets at the Australian facility, but some of these have since returned to service.

Uyuni Train Cemetery, Uyuni, Bolivia

Sean Kolk/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

This remarkable train cemetery is situated a couple of miles (3km) outside the Bolivian town of Uyuni, not far from the world's largest salt flats. A key tourist attraction, the cemetery usually draws visitors from far and wide, eager to capture its eerie ambience on film.

Uyuni Train Cemetery, Uyuni, Bolivia

Gerben van Heijningen/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

During the late 19th century, Uyuni was a major transport hub for Bolivia's mining industry. Commodities mined in the area were transported to the coast from the hub, and a railway was built by a team of British engineers.

Uyuni Train Cemetery, Uyuni, Bolivia

Arthur Lima/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The hub and rail network were championed by Bolivia's great and good (including the then-president Aniceto Arce) and the Uyuni area would have been buzzing with activity during this era.

Uyuni Train Cemetery, Uyuni, Bolivia

Urosr/Shutterstock

However, the boom times didn't last. Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the hub and rail network declined, as technical difficulties persisted and neighbouring countries protested a potential expansion to the network.

Uyuni Train Cemetery, Uyuni, Bolivia

hollykathryn/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The final death knell for the hub came in the 1940s when Bolivia's mining industry completely collapsed. The decimation of the industry hit Uyuni hard and its many trains were abandoned, where they remain to this day.

Train Graveyard, Kraków, Poland

True British Metal/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

One of the largest train graveyards on the planet, the Bieżanów Locomotive Depot in Kraków, Poland is home to hundreds of Soviet-era trains. The bulk of the abandoned stock comprises EU07 electric locomotives from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Train Graveyard, Kraków, Poland

True British Metal/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

These electric trains were based on the UK's British Rail Class 83 and are still used on rail networks in Eastern Europe today. Known for their robustness, many of the defunct trains are in surprisingly good condition.

Train Graveyard, Kraków, Poland

True British Metal/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

While the majority of the rolling stock in the Kraków graveyard is made up of EU07 electric trains, the boneyard also stores plenty of older locomotives, which date back decades, as well as several more modern trains.

Train Graveyard, Kraków, Poland

True British Metal/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Unlike many vehicle scrapyards in more urban locations, the trains that languish in Kraków's sprawling locomotive graveyard are largely graffiti-free, and don't appear to be affected too much by vandalism.

Train Graveyard, Kraków, Poland

True British Metal/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The lack of vandalism is all the more surprising given the graveyard appears to be severely neglected. Nature has been left to take its course and overgrown greenery surrounds the out-of-service trains.

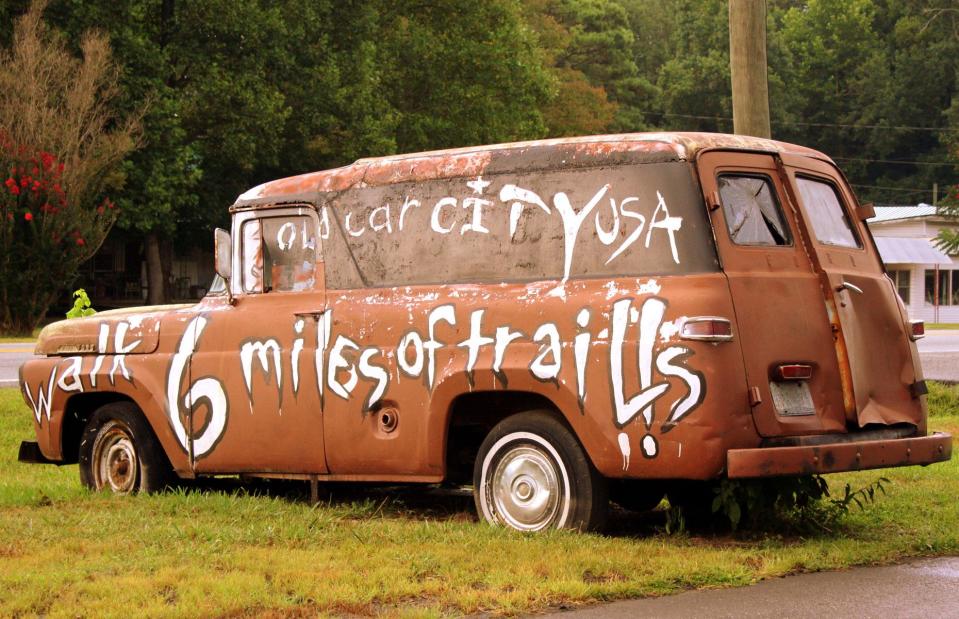

Old Car City, Georgia, USA

Dave Edens/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Georgia's Old Car City is one of the biggest classic car junkyards in the world. A treasure trove for enthusiasts, the enormous forested facility stores over 4,000 used vintage vehicles in various states of disrepair.

Old Car City, Georgia, USA

Mike Boening Photography/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The colossal scrapyard, which covers more than 32 acres in rural Georgia, was set up in 1931 by the parents of the current owner Walter Dean Lewis. Over the years, thousands of vehicles have lived out their final days in the yard.

Old Car City, Georgia, USA

Brent Moore/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Old Car City specialised in supplying classic car parts for decades until 2009 when Lewis realised he could make more money charging people to visit the scrapyard and turned it into an open-air museum.

Old Car City, Georgia, USA

Dave Edens/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

A lucrative enterprise, Lewis charges adult visitors £15 ($20) to enter the scrapyard. But if they wish to take photographs of the yard's thousands of Instagram-friendly used cars, the entry fee rises to £23 ($30).

Old Car City, Georgia, USA

George C Slade/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

It's not hard to figure out why Old Car City is such a magnet for both amateur and professional photographers. The scrapyard is jam-packed with auto gems, some of which have been parked for so long, they have trees and shrubs growing through them.

Desert Valley Auto Parts, Arizona, USA

Courtesy DVAP

Georgia's Old Car City may no longer sell spare parts, but this gigantic scrapyard in the sun-kissed Arizona desert is a flourishing business. Set up in 1993, Desert Valley Auto Parts near Phoenix sprawls over 40 acres, and could very well be the largest classic car junkyard on Earth.

Desert Valley Auto Parts, Arizona, USA

Devon Christopher Adams/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The scrapyard stores thousands of old cars dating from as far back as the 1940s and is America's go-to yard for vintage car aficionados looking for elusive spare parts to use in their classic vehicles.

Desert Valley Auto Parts, Arizona, USA

Devon Christopher Adams/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Desert Valley Auto Parts has such an enormous inventory, staff still haven't got around to sorting hundreds of old cars that have lived on the site for years, and may never get the chance to catalogue the yard's entire collection, which is constantly growing.

Desert Valley Auto Parts, Arizona, USA

Devon Christopher Adams/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Classic car enthusiasts who can't make it to the yard in person can shop for spare parts on the DVAP website. Although many of the vehicles are yet to be documented, staff put the most sought-after components online.

Desert Valley Auto Parts, Arizona, USA

Courtesy DVAP/Discovery Channel

The scrapyard is so renowned, it has even starred in its very own Discovery Channel reality show. Desert Car Kings, which ran on the channel for one season in 2011, followed the yard's employees as they went about their day-to-day business.

Alang Ship Breaking Yard, Gujarat, India

Sam Pabthaky/AFP/Getty

But where do cruise ships meet their end? Many of the industry's biggest operators including Carnival, Royal Caribbean and Marella send their vessels to a breaker's yard in Alang, India.

Alang Ship Breaking Yard, Gujarat, India

Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty

In fact, the famous ship breaking yard in the Gulf of Khambat is the global number one and recycles more than half the world's tired old cruise liners. Vessels in good working order sail there, while the most ailing craft are towed to their final destination.

Alang Ship Breaking Yard, Gujarat, India

Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty

Once they show up at their last port of call, the ships are run aground on the beach and secured by teams of wreckers, who start by emptying the vessels of fuel. After, the ship-breakers salvage any usable contents such as electronic equipment, fixtures and fittings, as well as furniture.

Alang Ship Breaking Yard, Gujarat, India

Adam Cohn/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Then the heavy work begins. The wrecking workers gradually break down the cruise liners, effectively deconstructing the vessels down to their skeletons. All in all, more than 95% of a ship can be repurposed meaning very little of the vessels end up in landfill.

Alang Ship Breaking Yard, Gujarat, India

Adam Cohn/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

However, the process isn't entirely environmentally friendly. Not by a long shot. Despite efforts in recent years to raise standards, the beach at Alang is severely polluted with all sorts of toxic nasties including asbestos, circuit boards and fuel that has leaked from the decommissioned ships.

Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard, Izmir Province, Turkey

Dave R/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

The second most important breaking yard for scrapped cruise liners is located in the Turkish port of Aliağa in Izmir Province. The yard is the final resting place of a number of iconic vessels that have been retired, such as Carnival's Fantasy and Inspiration (pictured) liners.

Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard, Izmir Province, Turkey

Chris McGrath/Getty Images

The global pause in cruising during COVID-19 accelerated the retirement and scrapping of many older and expensive-to-run ships. Although ships can take up to a year to dismantle, each vessel can fetch up to £3.4 billion ($4bn) in recycled material profits, so once-beloved ships line up at the docks to await their final fate.

Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard, Izmir Province, Turkey

Chris McGrath/Getty Images

In July 2020, Carnival Cruise Line announced that four Fantasy Class vessels were to exit the fleet. While some were sold as floating hotels, others including Carnival Imagination (right) were sent to Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard. Carnival Imagination is captured here next to the exposed hulk of its sister ship Carnival Fantasy, built in 1990.

Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard, Izmir Province, Turkey

AA/ABACA/PA

Ship-breaking can be environmentally damaging, but scientists and engineers are constantly working to find less destructive methods. These can include improving conditions for workers, breaking down ships away from the beach and isolating parts of the ship which could pose a danger to the environment.

Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard, Izmir Province, Turkey

Mike Burton/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0

Aliağa's ship-breakers also hold the badge for breaking down the world's first mega-cruise ship, the Sovereign of the Seas, which was formerly owned by Royal Caribbean. Its most recent owner, the Spanish operator Pullmantur Cruises, filed for bankruptcy in June 2020 due to COVID-19.

Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard, Izmir Province, Turkey

ND44/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 4.0

As a result of the pandemic, Pullmantur Cruises was also forced to decommission two other major vessels, the MV Horizon and MS Monarch (pictured). Mirroring the activity at the Alang Ship Breaking Yard, Aliağa's wreckers first salvage the ships' contents then dismantle the vessels, retaining the steel and metal scraps.

Aliağa Ship Breaking Yard, Izmir Province, Turkey

Fatih Takmakli/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 4.0

These metal parts are recycled on site or sent to a smelter or furnace to be melted, then ultimately re-used. In addition to the huge breaking yards at Alang and Aliağa, cruise ships are broken down at scrapyards in the UK, Bangladesh, China, Pakistan and other locations around the world.