See Classicism’s Thrilling New Generation of Artists and Artisans Show Their Stuff in Charleston

The kids, it seems, are definitely all right—especially when it comes to the classical tradition.

The evidence on inspiring display November 3-26, 2023, in Charleston, South Carolina, is the ICAA Student & Young Professionals Exhibition, a juried exhibition of artists and artisans who are solidly Millennial (or even Gen Z): age 35 and younger.

The show—60 works in media including painting and drawing, photography and printmaking, sculpture and stonework, metalwork and furniture making, scagliola plasterwork and even 3D printed plastic—is open to the public at the historic Aiken-Rhett House in partnership with the Historic Charleston Foundation. In the heart of a living city so engaged in preservation, it’s a fitting and vibrant demonstration not only of the broad technical expression of classical ideals in art and design today, but also the thrilling upsurge of a skilled and passionate coming generation of practitioners.

“The quality has blown me away,” says Peter Lyden, president of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA), which has helmed the exhibition—its first with a national call for entries—as part of its 2023 national conference, Enduring Places, in Charleston November 3-5. “This is museum quality.”

For Lyden, who oversees the 21-year-old national organization, the mission is to uphold classical design ideals that, while thousands of years old, have the power to inform and inspire work today both in preservation as well as the creation of new buildings and public spaces.

“Our mission at the ICAA is the holistic approach,” Lyden says. “While architecture is at the center, we incorporate all the other disciplines that interrelate, including landscape and interior design. And it is in our mission that artists and artisans provide that embellishment to the architecture. That’s why this exhibition is so important: We really are about the next generation training. We’re an education institute.”

To Lyden’s point, ICAA programming in its New York City headquarters as well as through 15 chapters across the U.S. offers classes, workshops, and programs for kids as young as middle school as well as continuing education for adults—there’s even a brawny filmmaking arm that often partners with PBS to further spread the mission. And it’s working.

Emily Bedard, one of the exhibition’s jurors, can testify. A traditional sculptor, Bedard took some freelance work in New York back in 2011: “They needed sculptors to execute some ornamental moldings in luxury apartments,” she says. With a new vision of the relationship of sculpture to architecture, the young artist signed on for a continuing education class at ICAA’s midtown Manhattan atelier.

“I learned to draw each of the orders—Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite,” she says. “It was a very welcoming community—practitioners from architecture and design offices as well as craftspeople—that made me feel like I could enrich my education and learn about these classical elements while also executing them in my job.”

Six years later, Bedard won the ICAA’s first-ever Award for Emerging Excellence in the Classical Tradition. “It was a turning point for me,” she says. “It encouraged me to buckle down, expand my horizons, and encourage young people to enter the field. To show them that there is a community here that is going to embrace you.”

The work of the ICAA was crucial, Bedard says, particularly because a late-20th-century dismissal of classicism for modernism wiped out a generation of skill transfer. “Classical art and artisanship are so dependent on the skill transfer from master to apprentice,” she says. With the Baby Boomers and Gen Xers shamed out of classicism during their educational years, that crucial relationship was endangered. “It was hard for the younger generation to find mentors.”

But now, thanks to two decades of ICAA efforts, the rising generation is flourishing. The call for entrants for this year’s exhibition was impressive both in number—300 entrants—and quality, Bedard says, echoing Lyden’s appraisal. “The high caliber of the work was really strong,” she says. “What delighted me about the entrants was the evidence of mastery—when you see a piece of work that is highly proficient in its execution but also has a freshness to it.”

It’s this freshness, Bedard points out, that is the key to understanding classicism’s role in contemporary architecture and art. “We talk about classicism having a certain vocabulary, but that you write new poetry with it,” she says. “So, it’s exciting to see when these [young] artists take these classical elements that we all know but bring them together to create something that still feels new.”

This point is not lost on the selected entrants themselves (all of whom received a $1,000 stipend to attend the conference; every artist or artisan is attending). Blacksmith Quinn McCay leaned into his training in classicism at Charleston’s American College of the Building Arts to inform his entry—a forged metal steel chair called “Comfort in Complexity”—but not define it.

“My piece isn’t directly classical in design,” he says, “although there is a lot of tradition within the piece. My greatest design influence was the Arts and Crafts Movement, which at its heart was a rejection of modern technology and a reimagining of design through the lens of traditional craft.” For McCay, this is where classicism is most valuable. “In my opinion it should be used as a tool for new styles of design rather than as a model or mold.”

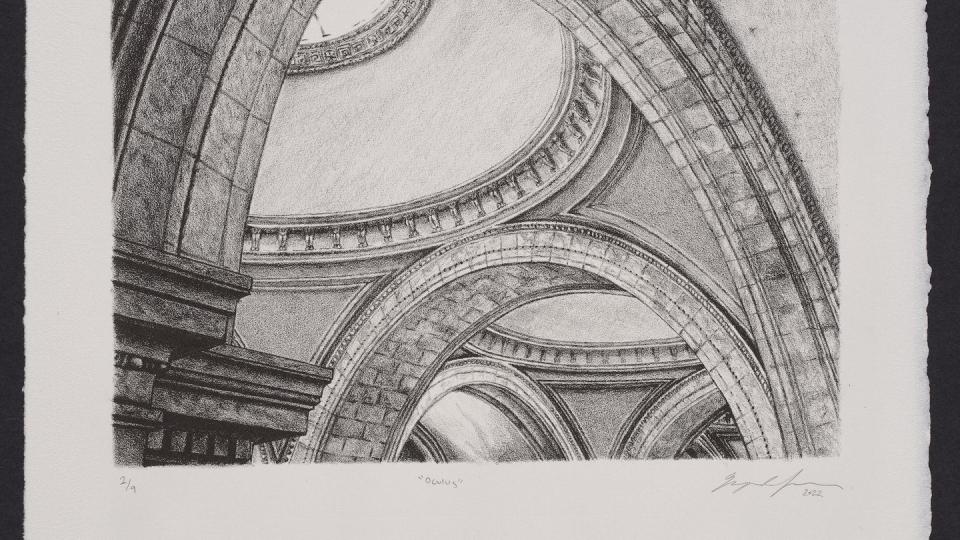

Georgina Renée Johnson, whose stone lithograph “Oculus” captures the delicacy of architectural drafting with the power of composition and form, combined her undergraduate training in urban studies and fine arts with work experience as an architectural draftsperson in Philadelphia—and found herself a rising classicist.

“I realized that classical architecture was infiltrating my artistic practice,” she says. “Sometimes my art ventures into the natural world, abstraction or more modern subjects—but overall, I am drawn to the beauty of classical elements and the transmission of light and shadow as they play across architectural details.”

For New Jersey-based sculptor Charlie Mostow, classicism inspired him to submit not a figure, but the space—a plaster “Aediculae for Artists”—designed to contain a figure. Mostow’s work with the ICAA—he’s an instructor—as well as travels to ancient sites in Europe, showed him the direct connection between architecture, sculpture, and space. “The space has character,” he says. “Being in those ancient places really reflected that. It feeds into my belief that the sculpture and the architecture become a unified expression of something in that place.”

His aediculae, which Mostow says is 35 inches tall, “could be in someone’s house, which is basically like a shrine. But it’s also a presentation model that could become something at monumental scale. At that point it becomes a public monument, a public space.”

For Mostow, the lesson of the monumental is deepened by the four years he has spent working with sculptor Sabin Howard on the United States National World War I Memorial, a 58-foot bronze relief scheduled to be unveiled in Washington, DC, on Memorial Day, 2024.

Much of the work, Mostow says, has centered around working with war veterans as models. “It’s about connecting to the human quality,” he says. “We’re doing something with people that have had this experience. These are modern people, and that translates into sculpture, even though it relies on the technique and tradition that goes back thousands and thousands of years. The nuance in the word classical for me is about the elevated spirit.”

And that, he says, is the classical ideal. “When people say classical, they think classical music,” he says. “And you know what, we’re not just playing our best version of Bach right now. We’re doing something new.”

ICAA Student & Young Professionals Exhibition runs November 3-26 at the Aiken-Rhett House in Charleston, South Carolina. For more information on the event and ICAA’s wealth of programs, go here: Institute of Classical Architecture & Art.

You Might Also Like