The Secret Superpower of OCD

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

On a February day in 2022, I arrived at the community pool in my Southern California neighborhood and adjusted my borrowed swim cap—a hand-me-down from my daughter, who’d worn it once when she was in second grade. I’d come with a single purpose: to attempt to swim a few laps. Honestly, I had little faith in my ability to do so. I had taken swim lessons as a child, and I knew I was competent enough not to drown, but actual lap swimming felt about as likely to me as growing wings and flying like a bird. I am not a naturally athletic person, but after relocating from New York to Los Angeles, I felt like I owed it to myself to at least live out the fantasy I’d had for years of swimming outdoors for exercise.

I gave myself specific guidelines and loopholes. First, a time limit: I only had to try for 20 minutes. Next, I gave myself a mantra: “My only job is to move my body from one end of the pool to the other, in any way possible.” I told myself I could just float or gently paddle, or even walk in the shallow end.

To my surprise, less than five minutes into that first 20-minute experiment, I was hooked. The water in the Olympic-size pool was clear and blue, and, thank goodness, lightly heated. Palm trees dotted its edges. I found I didn’t need to do all that much floating or walking. I was gliding. Weightless. Flying.

I did not, as per my fantasies, discover that I was preternaturally gifted at lap swimming or innately graceful in the water. I did not find it magically effortless. What I did discover, however, was that swimming laps gave me what years of yoga classes and scores of sporadically used meditation apps could not: quiet. Calm. Attention to the breath and nothing else.

As a neurodivergent person who has lived with obsessive compulsive disorder my whole life, this kind of quiet was new to me. My brain is always “on,” always busy—full of multiple strands of music playing and thoughts streaming and worries and lists, all running simultaneously. I also have synesthesia, a neurological condition in which a person experiences more than one sense at a time in response to a single stimulus—for example, seeing colors when one hears music, or tasting words—which adds another layer of perpetual input.

I liken my OCD to a puppy. If you get a dog and you don’t train it, it makes your life miserable. It chews up your shoes, wakes you up at night, and pees in your closet. But if you train the puppy, it becomes a source of unconditional love and immeasurable joy—cuddles and walks outside and new friends. Thanks to therapy and medication, the “dog training” in this metaphor, I have figured out how to embrace and utilize my busy brain. I have learned how to adjust the volume in my head, or to mask it with podcasts and audiobooks when it’s too much or I don’t want to be alone with my thoughts.

I’ve even come to see it as my creative superpower as a writer—a gift. When properly channeled, the endless “what ifs” and “what abouts” and “then whats?” that race through my mind (thanks to my particular sub-type of OCD) fuel the ideas that turn into my novels.

But then I started swimming and finally experienced the kind of clear, quiet mind that meditation gurus talk about. All the other stuff fell away.

Swimming is different from pure meditation, of course; in the water, focusing on breathing is survival, not a choice. The timing is non-negotiable—you can’t save it for later (when you’re underwater) or ignore it. You have to develop a rhythm, or you literally can’t continue.

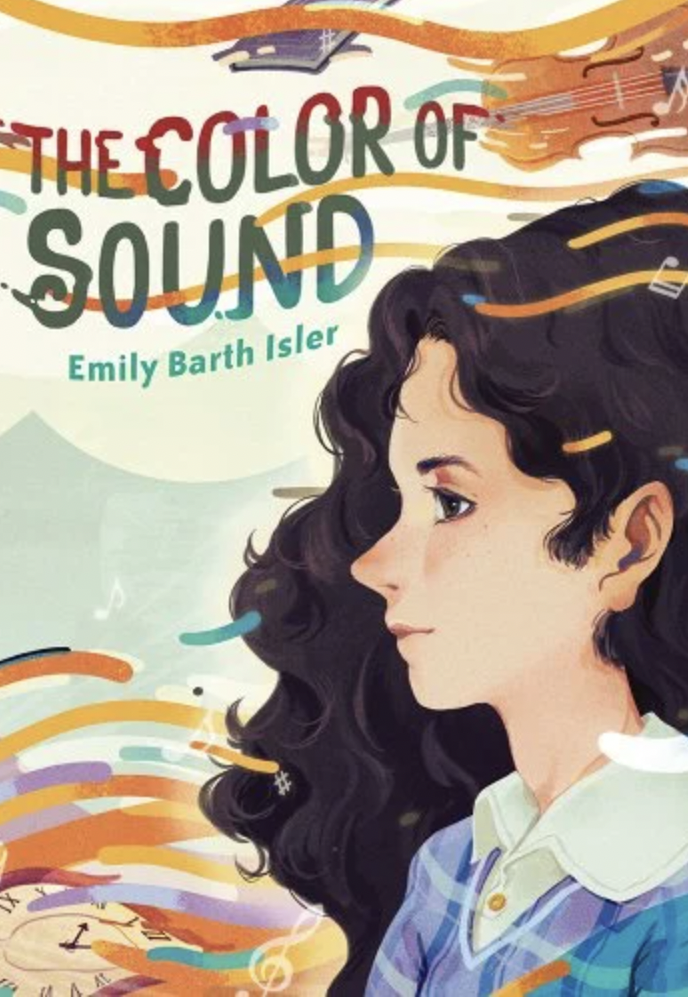

Once I got used to the quiet in my brain, something amazing happened: I found that I could let in a little bit of chosen noise, in the form of inspiration. That spring, I wrote most of my second book, a middle-grade novel called The Color of Sound, while alternating between breaststrokes and backstrokes. I positioned my iPhone on one edge of the pool, and between sets of laps, I typed plotlines in my notes app and recorded dialogue via voice memos. And since the main character in that book has synesthesia, I thought she might enjoy swimming for some of the same reasons I do. I turned her grandparents’ pool into a major plot point, and together, she and I explored the quieting of our busy brains, the absence of music, and the clarity of thought that comes with breathing and only breathing—at least for a little while.

Sometimes it felt like my characters lived at the pool, and I would go there to swim so I could visit them and let them tell me what happened next. Eventually, it felt like adding swimming into my plot of this book was a predestined inevitability. How could I have ever told the story without the pool, where a major plot climax eventually occurs? It now seems unfathomable.

Swimming is, naturally, rife with metaphors for both life and writing. When watching someone do the basic front-crawl stroke, it appears to be mostly about reaching, extending ever-forward. But that is only a piece of it. The actual forward motion happens because of the next part of the stroke, the displacement of water that occurs beneath the surface. Just like anything in life that looks uncomplicated or easy, there’s often a world of effort—pure grind—that nobody sees.

That first spring season of swimming was like falling in love. When I wasn’t swimming, I was thinking about my next swim, or remembering the joy of my previous swim. I made friends at the pool, marveled at the fact that in California I could swim outside year-round beneath a blue sky. I realized soon after I started that when I lift my head to breathe every few strokes or swim backstroke, I can look up at that sky and toward a majestic cluster of palm trees. I can watch airplanes make fluffy cloud streaks above. I can gaze in awe at the way the sun casts rainbows on the floor of the pool.

I’ve swum twice a week for two years now. It’s not always perfect. I question my practice on days when it’s 60 degrees or on the rare mornings when it rains in Southern California. But I just keep moving my body from one side of the pool to the other. I let ideas flow like the water. And I breathe.

The Color of Sound

bookshop.org

$18.59

Carolrhoda Books (R)You Might Also Like