Searching for Myself in Alice Neel’s Radical Portraits

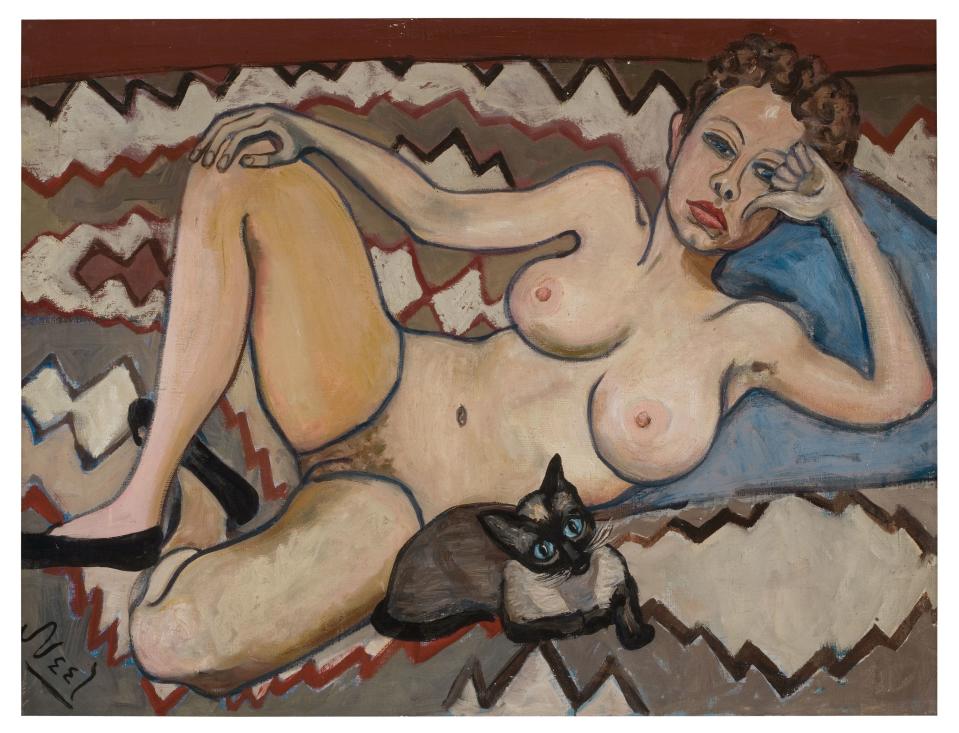

In December of 1978, a minor but newsworthy fracas erupted between the painter Alice Neel and the sculptor Pat Ladew, a Standard Oil heiress who, three decades earlier, had commissioned Neel to paint her portrait. Now, Ladew was dismayed to see that same portrait on the cover of an auction catalog that arrived by mail. In the painting, for which she had posed, at 19, wearing only a pair of demure black ballet flats, she appears pouty and languorous, propped up on one elbow, knees akimbo, a Siamese cat nestled into her hip mere inches from her pubic hair. (Likely it was Neel’s cat: At one point she kept nine of them in her Harlem apartment.)

This portrait had history. When the artist first sold it to her subject for a few hundred dollars, Ladew sent it back, demanding Neel add a pair of panties. She acquiesced but Ladew rejected the doctored version too. The panties came off. Neel held onto the canvas. Decades later, in her late 70s and in the midst of a career renaissance, she donated it to a benefit for nuclear deproliferation. It's hard not to read into the way she chose to title the painting: with Ladew’s full name.

Her subject threatened to sue, calling the portrait a “gynecological goodie,” and fretting that her Palm Beach grandmother might see the catalog and disinherit her. Neel’s retort was cutting, and slightly absurd. “Most civilized people,” she told the Chicago Tribune, “love nudes of themselves.”

Months later People magazine reached back out to a slightly more sanguine Ladew. “I respect Alice,” she granted. “But her stuff is too intimate to live with.”

The Ladew story is an extreme example, but it gets at the tension at the heart of Neel’s work: Who, in this day and age, is a portrait for? To vastly oversimplify, historically it was straightforward enough. The portraitist was a hired gun: I commission you, you flatter me, the result goes on my wall to show how important I am. Then came photography, then abstraction, then a new world order. For many of the decades Neel was working, her favored form was seen as pointless or downright taboo, a staid, bourgeois relic with no practical purpose and little currency in the modern art world. Even when Pop Art brought figuration back into the fold—and Neel’s star rose as a sort of dowager chronicler of ’60s and ’70s bohemia, with a late-in-life, long overdue retrospective at the Whitney—the portrait retained its musty why-bother funk, so much so that her estate still balks at applying the term to her work.

But Neel made portraiture into something else entirely. Most of her paintings were not commissions: She was brazen about approaching prospective models whose expressions, clothing, or way of carrying themselves caught her eye. “She’d always say, “I have to paint you,’ not, ‘Do you mind?’” remembers her daughter-in-law, Ginny Neel. That devotion to the form, even at its least fashionable, means Neel, who grew up middle class and bored in small town Pennsylvania, subsisted for much of her adult life on welfare checks. It means she never had a studio space in New York, making her paintings at home (first in a railroad flat in Spanish Harlem, where she moved from the Village in 1938, then in an Upper West Side apartment). These were intimate spaces that may, in fact, have helped incubate her very intimate portraits.

There were other factors too. She had a thing for unreliable men, and tired of the ones she could depend on. Born in 1900—two decades ahead of women’s suffrage—she made her way in the deeply misogynistic mid-century American art world (for a sense of both the chauvinism, and the distaste for portraiture: When Neel asked MoMA curator Henry Geldzheler, who sat for her in 1967, to include her work in a survey show of New York painters, he scoffed and said, “Oh, so you want to be a professional?”). She feared parting with her paintings—“I had a block against publicity, against the outside world. There’s something of the pack rat about me”—and was perversely good at undermining her own market. She also had had an aversion to the kind of painterly white lies that might have made her work more commercially viable. “I never want to work for hire,” she said, “because I don’t want to do what will please a subject.”

The fact is, Neel did not have to depict a person naked to make him or her feel very, very exposed. The artist’s portraits drift in and out of realism—eerie and lifelike here; sketchy, loose, and cartoonish there—but they offer a shocking jolt of reality, an uneasy sense of recognition that’s hard to shake. (The art critic Peter Schjeldahl called them “something that happens to you.”) In an oft-repeated quote, a Newsweek critic declared Neel in 1966 “an old pagan priestess somehow overlooked in the triumph of a new religion”—abstraction. Her “only harm,” he went on, “lies in her compulsion to tell the truth.”

That truth can hurt. An Alice Neel painting reflects the way people actually look: the tension that we hold in our mouths, hands and eyes; the stress we can’t quite unstitch from our faces without the help of a mirror; the awkwardness of existing within a body. (The art historian Linda Nochlin, whom Alice painted in 1973, called her work “portraits of a universal existential anxiety” that also illustrate “the relative painfulness of sitting for a portrait.”) It’s easy enough to compose one’s expression or posture for the time it takes to snap a photograph; it’s harder to do so over the course of multiple multi-hour interactive sittings. To be anachronistic, Neel’s portraits are the best rejoinder to selfie culture that I can think of.

Being painted by the artist, I imagine, may have felt like going to a fortune teller: You only think you want to know what she sees. Louise Bourgeois, Neel’s contemporary, refused to sit for her. When Neel painted Whitney director Jack Bauer, he, like Ladew, declined to purchase the outcome. So did art world power couple John Gruen and Jane Wilson. “If we did buy it,” Gruen remarked, “we wouldn’t have known where to put it.” In 1960, when she painted the poet Frank O’Hara, then a curator at MOMA with considerable sway over her career, Neel neatly exposed the fine line between beauty and beastliness: She completed two portraits, the first an achingly lovely depiction of O’Hara’s unconventional profile. In the second, he faces forward, snarling, wild-eyed, his forehead dotted with liver spots.

“My God! Those freckles!” he exclaimed when he saw it. Just as telling: He never championed Neel’s work, or included it in a show.

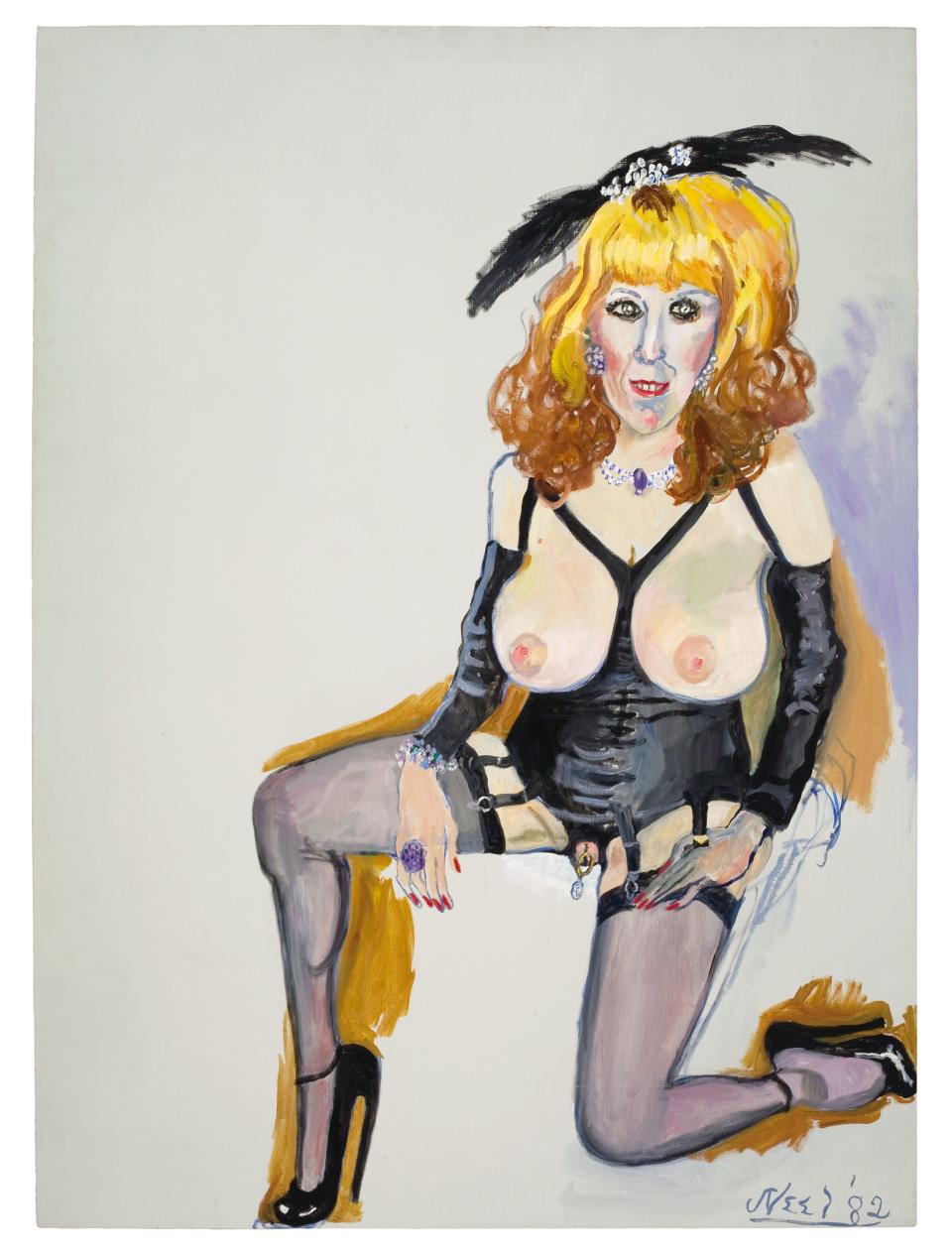

This week Pat Ladew goes on view at David Zwirner’s 20th Street gallery in Manhattan, alongside 30 or so of Alice Neel’s more radical paintings and drawings, most of them nudes. The show, organized by Neel’s daughter-in-law Ginny, with help from Zwirner’s Bellatrix Hubert, is meant to be something of a corrective for audiences more familiar with the artist’s portraits of glittery ’70s art and music scenesters, and the outrageous court jester public persona she cultivated in her waning years. (Zwirner’s last Neel outing, the 2017 exhibition “Uptown,” did something similar with a different body of work.). The new show is called “Freedom,” derived in part from a quote: “When you’re an artist you’re searching for freedom,” Neel said. “You never find it, ’cause there ain’t any freedom. But at least you search for it. In fact, art could be called the search.”

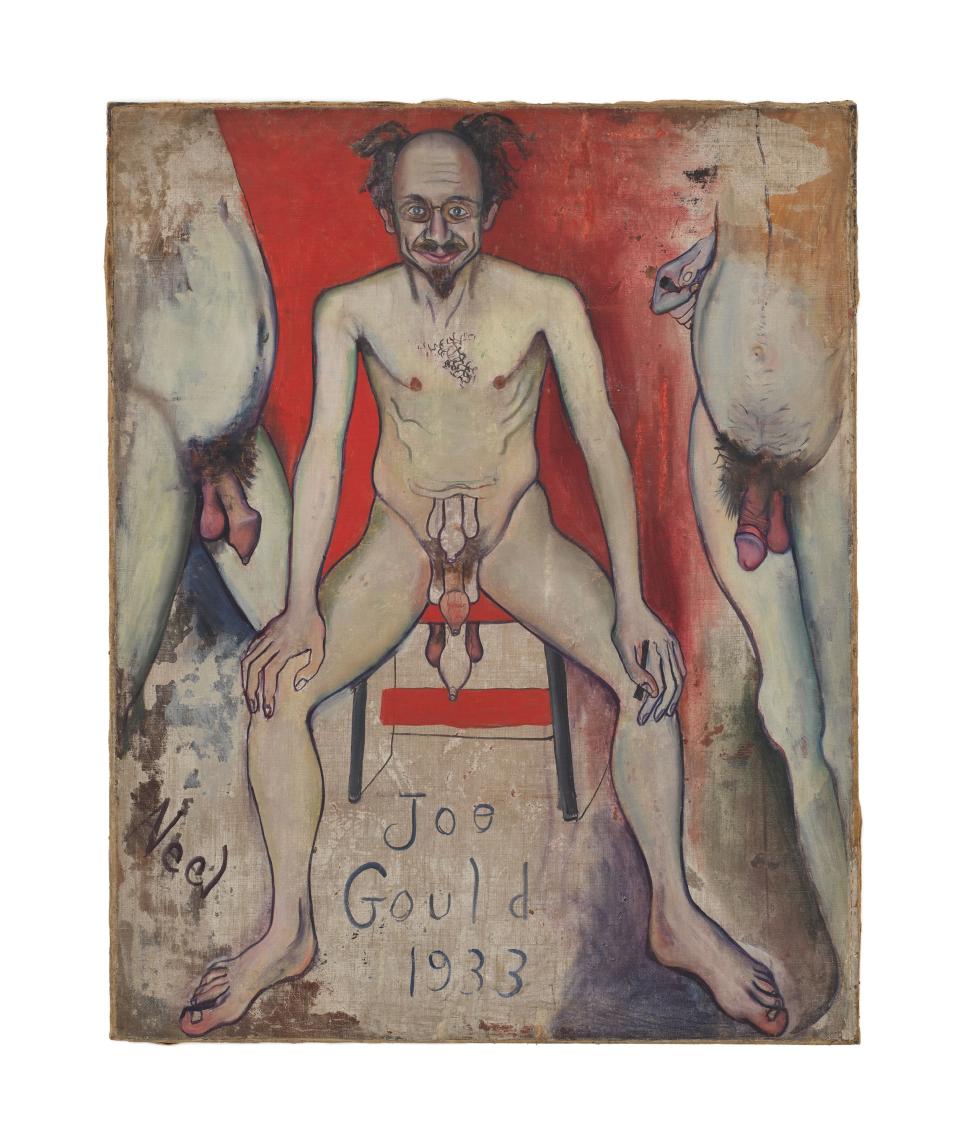

Neel had a similarly freewheeling philosophy when it came to her personal affairs. She had four children by three different men, only one of whom she married, and kept a bench of sometimes overlapping paramours. “Alice lived the liberation and therefore could paint what she painted,” says Ginny. “Freedom” is a show, in part, about taking pleasure in one’s sexuality. The best example appears in the catalog, but not in the gallery: Joie de Vivre (1935) is a prelapsarian fantasia in which Neel portrays herself as a frolicking pig, getting cheerfully dildoed by a shoe that her naked human lover has just flung from his foot. Another good example (this one will be at Zwirner): Neel’s 1933 rendering of the famed Greenwich Village eccentric Joe Gould, really a portrait—in quintuplicate!—of his uncircumcised penis. Jerry Saltz once wrote of the painting’s phallic abundance, “These are vivacious pricks, painted by someone who looked at cocks and was pleased and amused by them.”

It’s also a show about the consequences of sex, which are borne, Neel reminds us, largely by women. In Isabetta (1934), Neel painted her estranged daughter at 5 years old, naked and defiant, her puffy pudendum taking center stage (gallerists at the time refused to show the work, deeming it, in the current parlance, problematic). More disturbing to the modern eye are the grim, allegorical paintings Neel made about motherhood in the late ’20s and ’30s, a decade during which she endured a miscarriage; the death of her first daughter, Santillana, from diphtheria; the loss of Isabetta, whose father sent her at 17 months old to live with relatives in his native Cuba; the destruction of much of her early work by a jealous, drug-addled boyfriend; and a nervous breakdown, accompanied by multiple suicide attempts (she spent much of 1930 and 1931 in asylums). In Well Baby Clinic, Neel construes a maternity ward as a sort of frenetic zoo, with writhing infants—one of whom she compared to a bit of hamburger—as the main attraction. In Degenerate Madonna (1930), a mother, her breasts extruded into witchy teats, holds a rigid, ghostly babe, leaving us to wonder about the moral of the story.

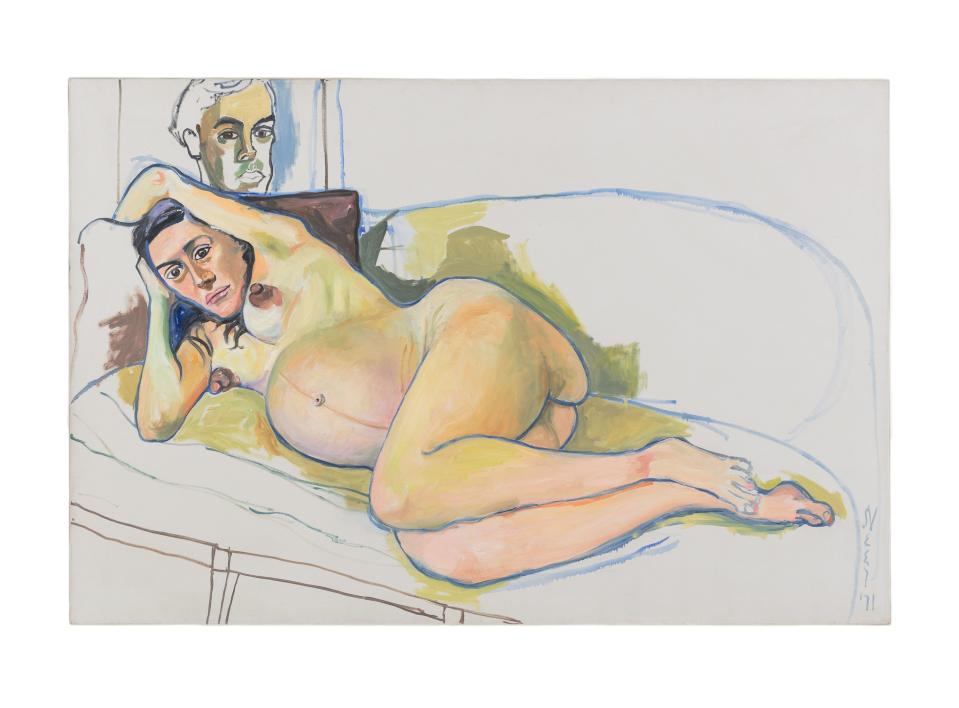

In her brilliant catalog essay, the curator Helen Molesworth observes about the show: “These are pictures of what it looks like to be curious about people when they are naked.” That’s never more true than in Neel’s remarkable paintings from the ’60s and ’70s of nude expectant mothers, including two of her son Richard’s first wife, Nancy. They are the exhibition’s high point—their drawn, pensive faces, ungainly bellies, and angry nipples controverting any romantic notions of pregnancy glow. They gaze at Neel warily, as if to say, “You better not turn me into some kind of fucking fertility goddess.” You can practically smell the hormones in the room.

Alice Neel died of colon cancer in 1984 and is buried in a meadow on the farm in Stowe, Vermont, where her younger son, Hartley, and his wife, Ginny, live. Her family interred her, at her own request, in the cheapest coffin available at the upper Manhattan funeral home where her body was taken. When I visit her gravesite one day in early January, the ground is covered in several feet of snow. The only sign that marks this as anything but a clearing in the woods is a metal sculpture of a horse, rearing or dancing on the far side of the field.

The Neels own 1,700 acres of this corner of Vermont, and Ginny keeps farm animals: horses, ponies, chickens, a rescue dog who lives in the barn, a flock of sheep, and a couple of llamas to herd and protect them while grazing. It doesn’t take me long to come to the conclusion that, in their marriage, Ginny is the llama and Hartley is the sheep. He’s a radiologist. His brother, Richard, was, at one point a corporate lawyer and a self-professed Nixonian Republican (their mother was a sort of casual communist, though, says Ginny, “Dogma was not her thing”). The strange wrinkle in Alice Neel’s otherwise bohemian biography is that she managed to give the two children she raised to adulthood the best educations available: scholarships to an Upper East Side prep school and a New England boarding school and Ivy League degrees. The boys became, for lack of a better word, squares. Or so I think until I meet Hartley, who wears a beret and a gold cuff inscribed with the Schrödinger equation and is prone to outlandish non sequiturs and what he calls “flights of idea.” He is eccentric enough that one night over dinner, he gifts me, with great formality, a Ziploc baggie full of buttons printed with Neel family photographs. It occurs to me that a radiologist does something not unlike a portrait artist. He looks inside people, he interprets images, he tries to understand.

Schrödinger’s theorem described the wave function of quantum-mechanical systems. His work begot that of Heisenberg, whose famous uncertainty principle can be abstracted to say something about the nature of making a portrait (and I suppose of reporting an article too): You can’t know both the momentum and precise location of an object at once; you can’t see something without affecting the thing you’re looking at. Neel’s portraits are the result of her perspicacious eye, but also of some unknowable alchemy created in the room where they were made, what the New Yorker theater critic Hilton Als, who curated Zwirner’s last Neel show, called “a pouring in of energy from both sides.”

Ginny credits her mother-in-law with changing her life. She was a cloistered undergraduate at Wellesley in the early ’60s when she first caught whiff of the legend of Alice Neel, a New York City artist who painted what she wanted and lived how she liked and generally “did everything you weren’t allowed to do.” She got to know Neel and even lived with her for part of a summer before she began dating the artist’s son. Ginny sat for Neel many times—though, curiously, never nude—and several of those portraits hang on the walls of her Vermont house. In some, Ginny, who is strikingly beautiful in her 70s, appears slightly haggard, but she resents the way people—including me—sometimes talk about Neel’s work: “‘Oh, Alice Neel, warts and all.’ She wasn’t trying to not be flattering. When painting you, she seemed to be totally empathetic. She wasn’t judging. She was trying to just get who you were. Weirdly, you were less self-conscious.”

I’ve come to visit Ginny and Hartley to learn more about the Zwirner show, but I’m also here to spend the night in the little 18th-century log cabin where Neel set up shop to paint when she visited, which she did frequently in her last decade. Though they’ve since added guest quarters and a kitchenette to the back of the cabin, the family has preserved the studio space as the artist kept it. In one corner is her easel, her paint-spattered cane and blue polyester smock—size large—still hanging from it. There’s a little spindle back chair where she would sit to work, the easel tipped forward so she could reach the whole canvas (it might account for why her figures often seem a bit top-heavy). In one corner of the room there’s a wood stove and a pile of logs; in another, a cardboard box labeled “Alice’s things” that’s filled with crusty tubes of paint.

When Als made this same trip a couple years ago, he took a picture of some of Alice’s dresses that hang on a nail on the studio wall. He later gave a speech in which he described feeling tempted to try the dresses on. Instead he posted his photo to Instagram. Alone in the cabin at night, I show no such restraint, slipping Neel’s smock over my sweater and taking a photo of myself in the mirror of the little bathroom that didn’t exist when she worked here. I text the picture to a few friends but don’t go so far as to put it on social media. No one told me not to touch her things, but doing so feels illicit, and dressing up in her painting uniform, to be honest, feels a little too on the nose.

The truth is I only sort of know why I came to Vermont, on a trip I’ve taken at my own expense. It’s a pilgrimage, I guess. I want to understand why Alice Neel had to make portraits, because I want to understand why I’ve always had to make them too. In one of my early memories, I’m with my dad at a restaurant, sketching faces on the paper tablecloth. He asks (innocently, I’m sure): “Don’t you get sick of drawing the same thing over and over again?” I feel embarrassed—even at 6 or 7 I sense the intrinsic value judgment—but the fact of the matter is I didn’t, and still don’t. It’s a magic trick I’m keen to attempt every time, an always open question: What does it mean to represent in two dimensions what speaks well enough for itself in three? What does it take to capture someone’s likeness, or, better yet, some fundamental insight into their character or orientation toward the world? What more interesting way is there to understand another human being?

Neel described her own practice as almost an addiction. “If I don't paint for certain lengths of time,” she said, “I get into frightfully morbid moods, but the minute I begin to work, I’m cured.” Making portraits was “a way of coming to grips with” lifelong anxiety, a mediated interaction that nourished her and sometimes, after the fact, left her wiped out, “an untenanted house.” From another angle, that sounds vampiric: I will possess your body so I can escape my own.

In 1979 she told a New York magazine interviewer: “You know what it takes to be an artist? Hypersensitivity and the will of the devil. To never give up.” To compare our talents—hers: massive, proven; mine: inchoate, possibly middling—is absurd. But using her own lingo: I might have had the sensitivity, but I woefully lacked the will. I went to college intending to paint and gave up by day two—not the portrait-making, which I’ve continued to do as a sort of tortured, wistful sideshow, a slightly painful reminder of my own risk aversion, but the idea that I might elevate it to something more. I had received the same messages that Neel must have heard: Portraits are a lesser art; you might as well be a sidewalk caricaturist. I internalized those ideas, an electron knocked askew by a few sideways glances. She, thank God, did not.

She once observed, “The self, we have it like an albatross around the neck.” When I graduated college as an English major—soon to go into book publishing and later journalism—I wrote my senior thesis on Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Grey. “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter,” Wilde wrote. “The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion.” It’s only a decade and a half later that the significance of my choice comes into focus; I picked a novel about a person whose life is haunted by a portrait.

Alice Neel, who had a decidedly prickly side, would, for the record, have hated this part of this essay. “If someone came to her and said, ‘I’m an artist,’” Ginny remembers, “she would say, ‘Oh, have you been at the Whitney?’”

The British figurative painter Lucian Freud once told an interviewer, “I feel a certain obligation to do the self-portraits. It keeps me honest.” Neel felt no such duty. For most of her career she left herself out of it, making use of her own image only in a few drawings and diary-like watercolors (this speaks also to her remarkable comfort requisitioning subjects to sit for her—for many portraitists, depicting oneself is a necessity). As Frida Kahlo put it: “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

I’ve drawn and painted myself many times, but it’s been far harder than I anticipated—distressingly hard, in fact—to write about my own conflicted relationship to painting. That, I suspect, is a feeling Alice Neel might actually relate to. In 1975, she began work on a piece that would become her first and only major study of herself. “I almost killed myself painting it,” she said, at one point shelving the project for years.

She finished in 1980. It was half a decade—or maybe eight decades—in the making, but the result is unprecedented, what Neel’s biographer, Phoebe Hoban (her book, Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty, is an essential resource), called “an audacious and unexpected grand gesture of an artist at the top of her form.” Neel pictures her octogenarian self, white-haired, bespectacled, and perched bare-naked on the same blue and white striped settee in her Upper West Side sitting room where so many models sat before. Her breasts droop; her navel frowns; her ankles bulge; her shoulders slump. Where another granny might clutch her knitting needle and skein of yarn, Neel has a paintbrush and a white painter’s rag. Her expression seems stern at first. Then you notice a slight lift of the brow, a flare of the nostril, a pull at the corner of her lip. She may be suppressing a smile.

The painting is probably Neel’s most famous nude—and almost certainly her most incisive expression of the freedom she sought—but it’s glaringly absent from the Zwirner show. Ginny couldn’t wrest it away from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., where it hangs alongside works by Diego Rivera, Andy Warhol, and Edward Hopper in the museum’s current exhibition of artist self-portraits. The gallery had to settle for putting it on the cover of the catalog.

And that, perhaps, is Alice Neel’s best last laugh: nakedly herself, sui generis, and hot in demand up and down the Eastern seaboard.

As for me? Well, I suppose it takes a lifetime to be so free.