Searching for Bone Marrow Can Be Harrowing For Anyone — But It's Especially Difficult for People of Color

In April 2017, Roxie Meza, of Bradenton, FL, posted an adorable picture on social media of her infant daughter, Emilie, sitting in a green plastic high chair, her fine hair forming a sparse halo of messy dark curls around her smiling face. But Roxie wasn’t fishing for “Likes” — far from it. The caption, written in Emilie’s voice, read I need you to help save my life.... Emilie’s family had recently learned that the little girl had leukemia and needed a bone marrow transplant.

Emilie’s health journey had actually begun a couple of months before, when she was 7 months old. Out of the blue, the thriving infant started displaying unexplained fevers, diarrhea and lethargy. The first two doctors who examined Emilie thought she had a virus. A third apparently suspected anemia, and she received two emergency blood transfusions.

Then, about two months after the mysterious symptoms began, Emilie woke up looking pale. When Roxie changed her diaper and saw blood in her stool, she and her husband, Eduardo, rushed their baby girl to the emergency room at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in nearby St. Petersburg. Samples of Emilie’s blood and bone marrow were sent to the lab — and she was admitted. “They put us in the oncologyunit, but I was so focused on Emilie’s well-being, I didn’t think about what that meant,” recalls Roxie, 33, a stay-at-home mom. “I walked into the hallway and saw two little kids who were bald — and it hit me like a slap in the face: Emilie could have cancer.”

A few days later, a doctor confirmed the diagnosis. Emilie had acute myeloidleukemia, a rapidly advancing type of blood cancer that strikes about 730 children under 20 in the U.S. every year. “I felt so many emotions all at once — fear, shock, sadness, worry, disbelief,” says Roxie. “It was like a scene from a movie where the actor is standing stock-still and everything around them is swirling.”

Seventy percent of the blood cells in Emilie’s bone marrow — the soft, spongy tissue inside the bones where blood cells and platelets are made — were abnormal white cells known as myeloblasts. These leukemia cells were proliferating so fast, they were crowding out Emilie’s healthy cells. As a result, her numbers of normal white blood cells (which fight infection), red blood cells (which deliver oxygen tothe body’s tissues) and platelets (which promote clotting to prevent out-of-controlbleeding) were getting dangerously low.

Emilie started intensive chemotherapy the next day. After five weeks, her blood was still swarming with cancer cells, so a new doctor, hematologist-oncologist Benjamin Oshrine, M.D., who handles bone marrow transplant cases, took over her care. Bone marrow transplant is a common treatment for pediatric AML patients who don’t respond well to chemotherapy. By taking bone marrow from a healthy donor and transfusing it into a patient with leukemia or another blood-related disorder, doctors can often cure these otherwise fatal illnesses. Unfortunately, Emilie faced a significant hurdle: The key to the treatment’s success is finding a bone marrow donor who is a good match for the patient, but the Mezas are Hispanic. Locating an ideal donor is a daunting challenge — often an insurmountable one — for people of color.

WHY ETHNICITY MATTERS

Finding a bone marrow match goes beyond blood type matching, Dr. Oshrine explains. The most important elements are human leukocyte antigen (HLA) proteins on the body’s cells. HLA proteins are dictated in part by ethnicity, but they can vary among people of the same race and even among people in the same family. “HLA proteins are linked to your immune system, which is shaped by your ancestors’ geography and experiences, whether they lived through pandemics or wars or mass migrations,” explains Abeer Madbouly, Ph.D., principal bioinformatics scientist at the National Marrow Donor Program’s Be the Match Registry, a non-profit that recruits donors and connects them to patients in need.

HLA markers are important to a transplant’s success because the immune system uses these markers to identify which cells belong in the body and which don’t. If a donor’s marrow is a poor match, the immune cells in the new marrow will attack healthy cells in the recipient’s body, a potentially fatal transplant complication known as graft-versus-host disease.

To find a match for Emilie, Dr. Oshrine tested the blood of her three older siblings (one sister is a full biological sibling, and another sister and a brother are half-siblings), but none had HLA markers that matched hers, which was unsurprising because the likelihood of a full sibling being a close match is just 25%. Roxie and Eduardo were both half matches, as a child gets half their HLA from each parent. If absolutely necessary, one of them could donate their marrow, thanks to recent advances that minimize graft-versus-host disease with half matches. But the ideal donor is a full match, even if they are a total stranger.

The hospital’s transplant team searched the Be the Match Registry. With 22 million potential donors worldwide, Be the Match connected 6,426 people who needed bone marrow transplants with lifesaving matches in 2019. But people of color are not well represented in its data-base, partly because of deep-seated distrust of the medical system, says Akiim DeShay, the founder of BlackBoneMarrow.com, which promotes awareness of Black bone marrow donation.

Since the time of slavery, when doctors performed experimental gynecological surgeries on women, Black people in particular have been abused and taken advantage of by the medical establishment. “Many of us heard family stories of relatives who walked into hospitals and never came out or were admitted and sent home too early,” says DeShay, who received a lifesaving bone marrow transplant in 2004, when he had leukemia. And the problem continues: A 2017 NPR poll found that 32% of Black Americans and 20% of Latinos said they’d been discriminated against at a doctor’s office or a health clinic.

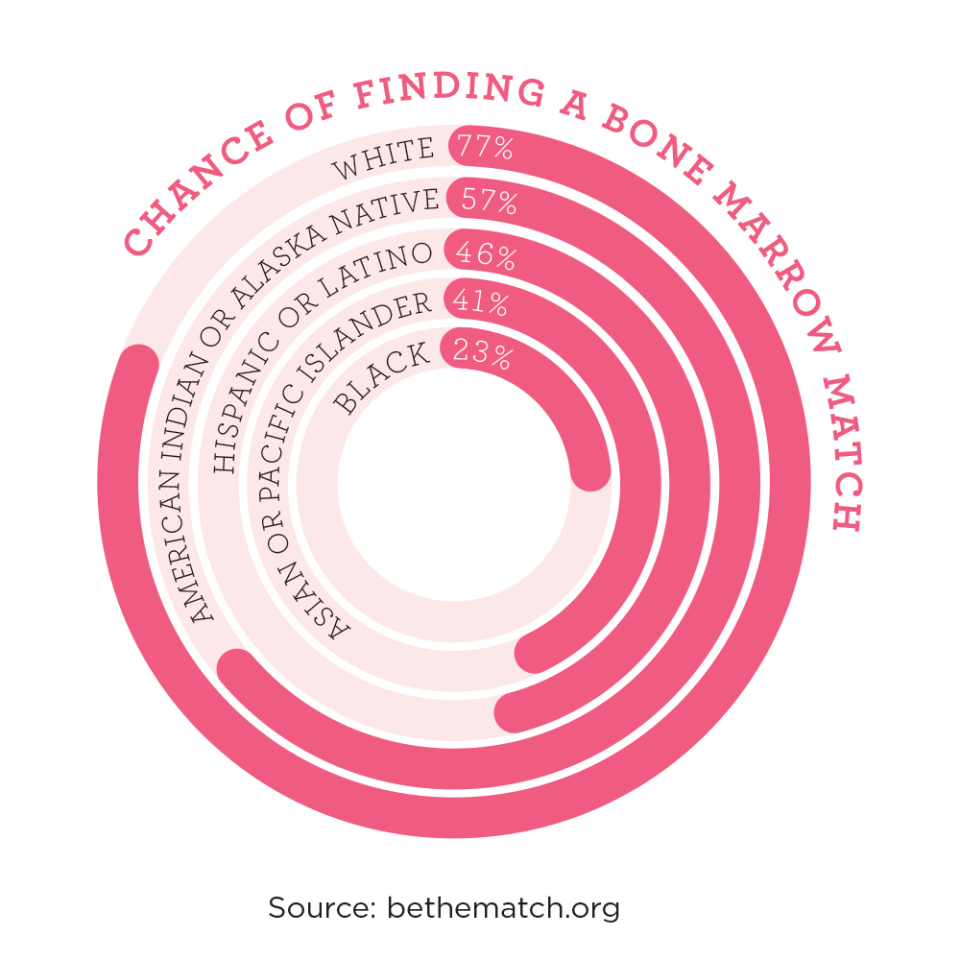

The registry reflects these issues. While white people have a 77% chance of finding a match, the odds plummet from there. Hispanics like the Mezas have just a 46% chance of finding a match.

The paucity of diverse donors has heartbreaking consequences. Jasmine and Sven Hamilton, who live in California’s Bay Area, worked diligently for two months to find a match for stem celld onation for their mixed-race son, Savian, now 6, who was diagnosed with peripheral T-cell lymphoma in September 2019. After they came up empty-handed, Jasmine, a half match, donated her stem cells — but Savian has been battling a severe case of graft-versus-host disease ever since. “I encourage people in all communities to educate themselves on bone marrow and stemcell donation and understand what it means to families,” says Jasmine, who is Black. “The pain of watching your child go through something like this is indescribable.”

THE RACE TO FIND A DONOR

Emilie didn’t match with anyone in the registry. Worried and disappointed, Roxie turned to social media. “I started posting about Emilie’s need for a bonemarrow donor, and it snowballed,” she recalled. “Total strangers started holding bone marrow drives on Emilie’s behalf. There were drives in Florida, near where we live, but women in Utah, Tennessee and California organized them as well. We were absolutely shocked and overwhelmed by people’s kindness and generosity.”

As Roxie revved up the donor search, posting updates about Emilie’s health almost daily, Emilie was in the midst of her second round of chemotherapy. Prior to transplant, doctors use chemotherapy to kill as many leukemia cells as possible and disable the recipient’s immune system so it won’t reject the transplant. Once the new bone marrow takes hold, it creates a healthy new immune system inside the patient.

“I was living in the hospital with Emilie, since I couldn’t expose her to any outside germs,” recalls Roxie. “Emilie weathered the first chemo round fairly well. But during the second round, she spiked a persistent fever.” When Emilie had to go to the ICU, Roxie felt helpless: “Something terrible is happening to your child, and you can’t do anything about it.”

Within a few days of the crisis, Emilie’s health bounced back, but the scare pushed Roxie’s stress to a whole new level. “I never let myself think about the fact that we might lose our sweet girl, but I came pretty close to imagining the worst in that moment,” she says. “Fortunately, Emilie is incredibly strong. Her ability to handle everything she went through was remarkable.”

Even the nurses and doctors weres truck by Emilie’s resilience. “She was always smiling, no matter how intense her treatment was,” recalls Dr. Oshrine.“From the time the Mezas learned that Emilie needed a transplant and the difficulty of finding donors, they became passionate about increasing donor options for everyone — and they worked tirelessly at it while their child was going through chemo, an extraordinarily difficult time for any family.”

Two months after the Mezas’ donor search began, more than 10,000 people had registered with Be the Match in hopes of helping little Emilie — a record for the registry at the time. But not a single person had marrow compatible with hers. “We wanted a full match to ensure the best possible outcome for our little girl, but Emilie couldn’t wait any longer,” says Roxie.

AN IMPERFECT GIFT

Without a perfect volunteer, the Mezas and Dr. Oshrine decided they’d use Eduardo’s marrow, the next best thing. Even five years ago, using a donor who was a half match was impossible because the risk of graft-versus-host disease was too high. But researchers discovered that administering a combination of medications at a specific point after transplant significantly reduced the risk.

Still, bone marrow transplants are risky. “In kids like Emilie, they are successful about 70% of the time,” says Dr. Oshrine. “In about 5% to 10% ofcases, the patient develops an infection because the intensive pre-transplantchemotherapy wipes out their immune system. And in 20% or so of patients, the disease returns after the transplant.”

At 5:30 a.m. on June 15, 2017, Eduardo arrived at a hospital 45 minutes away from Emilie’s. Doctors made tiny incisions on the back of both sides of his pelvic bone and used hollow needles to withdraw a small amount of his liquid marrow. “I was worried that my bone marrow wouldn’t help Emilie, since I was only a half match, but I liked the idea of her getting mine instead of a stranger’s,” says Eduardo. “And I was willing to do whatever it took to save my little girl." When he awoke a few hours later, he felt sore and sluggish. “But I got out of bed and started pacing back and forth to get the anesthesia out of my system so I could get to Emilie in time to see the transfusion,” he says.

When he arrived at Emilie’s hospital room in midafternoon, Roxie was holding their sleeping baby in her arms, and what looked like blood in a bag was dripping through a tube into Emilie’s body. After the drama of the prior months, the transplant itself was anticlimactic. But inside their child’s body, something remarkable was happening. As Eduardo’s marrow entered Emilie’s veins, its cells, which had built-in homing devices, migrated straight to her bone marrow, where they would begin the lifesaving process of repopulating her depleted tissue with healthy new cells. “Knowing the marrow from my bones had the power to cure Emilie was one of the proudest moments of my life,” says Eduardo.

BACK TO CHILDHOOD

Emilie had to stay in the hospital for nearly two nerve-racking months after her transplant. “The chemo had wipedout all the cells Emilie needed to survive, so she had to have blood transfusions almost every day,” says Roxie. “Without healthy immune and blood cells, she had terrible diaper rash and bruises everywhere. But by week three, the doctors told us the new cells were starting to implant and there was evidence her immune system was regenerating. At that point, I felt like we could start to relax a little.”

The day they went home, Emilie wore a Supergirl costume, complete with a red tutu. As they walked down the hallway, Emilie in Eduardo’s arms, the staff sang, “If you’re happy to go home, clap your hands.” Emilie clapped and beamed, clearly delighted at all the attention, then rang a bell symbolizing that she was done with in-hospital chemo. When Roxie posted a video of the scene, 1,000 people liked it and nearly 400 shared it. “I’llnever forget that moment,” says Roxie.

Today, Emilie is 4 — and incredibly healthy. “She rarely gets sick. She loves to sing and learn; she loves sparkly clothes and anything blue,” says Roxie.“Her favorite toy is a little bear. She listens to its chest with a stethoscope and takes its temperature. And her best friend is her daddy. The two of them have a beautiful connection.”

Emilie’s difficult journey had another heartwarming outcome: “We’ve heardthat some of the people who donated in Emilie’s name may have been matches for other kids in need,” says Roxie. Says Eduardo, “It’s stressful knowing there’s a treatment that will save your child’s life and not being able to find the right donor. I wouldn’t wish that on anyone.” He adds,“We all have the means to give bone marrow to someone who is sick and suffering, whether we know them or not. If a doctor called me today and told me my marrow could help save someone else, I’d say, ‘Just tell me when and where to go.’ ”

This story originally appeared in the December 2020 issue of Good Housekeeping. Subscribe to Good Housekeeping here.

You Might Also Like