In Search of Fatima Lakhani, Whose Cookbook Changed the Way My Family Ate

My father had triple open heart surgery in the fall of 2003, when I was 10 and he was just shy of 52. It was a long time coming: He’d been chain-smoking since the age of 14, and at his worst, he demolished three packs a day. The surgery left a stitched scar in the middle of his chest, patched together like the lips on a Raggedy Ann doll. The aftermath demanded a complete overhaul of his lifestyle, and, by extension, the rest of the family’s. We bought him a stool to sit on when he bathed himself. For exercise, he would pace an indoor mall, making three or four laps.

It also required a dietary facelift, so he and my mother visited a nutritionist, who gave them clear instructions: Eat out less. Cook at home more. Buy a “heart-healthy” cookbook. My parents found Indian Recipes for a Healthy Heart on Amazon the next day. It arrived promptly, a stiff, pale-pink paperback. The author identified herself as “Mrs. Lakhani,” conjuring the image of a schoolmistress. On the back cover, there was a photo of a stately woman with fair skin and a sharp nose wearing a sari the color of watermelon flesh.

This mysterious Mrs. Lakhani gave my mother lessons she found invaluable: She stopped using chicken legs, instead only breasts, and removed all the visible fat from the chicken. She cut out red meat. She used oil sparingly. This was terrible news for my father, who bragged about how he once ate 20 luchi, flatbreads my mother deep-fried punishingly in ghee until they inflated into pimply little saucers, in a single sitting.

FatimaLakhani-pickup1.png

Released in March 1992 by the now-defunct Fahil Publishing Company, Indian Recipes for a Healthy Heart belongs to that category of cookbooks written for patients in cardiac recovery and the people who don’t want to become them. As food historian Marion Nestle explained, this genre is thought to have begun with Ancel & Margaret Keys’s book, Eat Well and Stay Well in 1959, followed by The American Heart Association Cookbook in 1973. Today, it has swelled to the point of over-saturation; the phrase “heart healthy cookbook” yields nearly 200 results on Amazon alone.

Lakhani’s was the only cardiac recovery cookbook my parents could find that focused on Indian cooking. In its opening pages, three cardiologists extol the virtues of Lakhani’s diligence in the face of her spouse’s heart disease. The longest of these forewords, from cardiologist Vidya S. Kaushik, comes with hearty dose of alarmism. “Enjoy the delectable dishes in this book and beat the odds of being another statistical blip on the cardiac epidemiologist’s graph,” he writes. Eat so you don’t become a number.

Lakhani outlines the book’s origin story in the introduction: A few years after they wed, Lakhani and her husband became aware of his high blood cholesterol. Their doctor gave him “a handful of low-cholesterol, low-fat English recipes,” which they found bland and sterile. They fell back on old habits with marginally more healthful substitutions—Indian food cooked in vegetable oil or margarine instead of butter—and excised red meats, whole milk, eggs, and cream. But these measures didn’t safeguard her husband from bypass surgery years later. Lakhani realized that eating well required a more significant dietary shift. Determined to make a change, she looked for heart-healthy Indian recipes but couldn’t find any.

So she wrote her own, modifying a book she’d been writing based on her “favorite classical recipes” from India, and wedding it to her newfound holistic philosophy about heart health. “[A] good diet, although a very important factor, is not sufficient for achievement of good health—other lifestyle factors such as exercise and stress management are equally, if not more, important,” she writes. She spends seven pages mapping “three pillars” for overall fitness: exercise, diet, and stress management.

indiancooking-latimesarchive.png

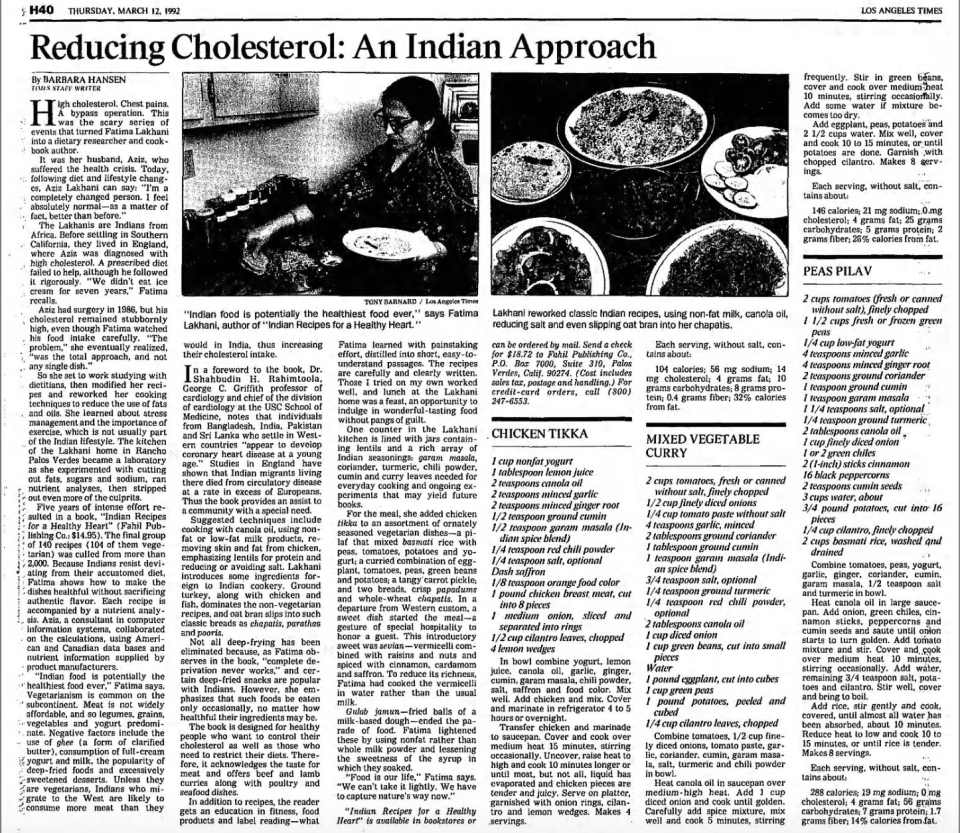

A March 1992 story in the Los Angeles Times gives slightly more color to the story Lakhani sketches. Mrs. Lakhani’s first name, I learned, is Fatima. She and her husband, Aziz, were “Indians from Africa” (an author biography names Kenya for Fatima) who lived in England before moving to the town of Ranchos Palos Verdes in southern California. “I’m a completely changed person,” Aziz told the paper of the family’s new diet. “I feel absolutely normal—as a matter of fact, better than before.” Fatima made it clear that she was writing against the idea that Indian food is so oil-rich that feeding it to someone is tantamount to gastrointestinal assault. “Indian food is potentially the healthiest food ever,” she told the paper.

The book’s back cover refers to Fatima as an “accomplished culinary artist” who taught Indian cooking classes in Los Angeles. A Los Angeles Times ad from October 1985 states that, for 90 dollars, you could get a four-session “Indian hors d’oeuvres class” in what appears to be her home in Rancho Palos Verdes. “A TASTE of INDIA—Dinner with Fatima Lakhani,” reads a December 1985 ad; for a three-hour $20 session, she would give you “an opportunity to explore festive dishes from India,” which entailed making lamb biryani, kebabs, and an avocado pear dessert.

My family’s dependence on this book didn’t last forever. My mother cooked through the book with consistently diminishing returns. As time passed, she grew dismayed by the use of margarine in an era when health-conscious America was becoming hip to the perceived sin of hydrogenated fats, coupled with growing societal suspicion surrounding the causal link between high cholesterol and heart disease, distilled in 2007’s Good Calories, Bad Calories by Gary Taubes. She tried making some samosas in her oven, and they emerged hard as stone.

In the book, these samosas are called “exotic vegetable triangles,” and chicken biryani is “festive chicken and rice,” as if promising a gastronomic safari. It’s the kind of terminology that seems straight out of a Colonial-era playbook. Such language, I initially rationalized, was a condition of Fatima Lakhani’s era and the cultural currents she swam against. Then I remembered that Julie Sahni refers to aloo samosas in 1980’s Classic Indian Cooking as “savory pastries with potato filling,” with no vocabulary of exoticism. Lakhani’s language doesn’t quite square with the quotes of a woman who speaks of the tired misconceptions that get stuck to Indian food. In an article in the Los Angeles Times in January 1991, she expresses dismay at how Indian cooking has become “synonymous with curry,” a misconception many still bemoan today.

Who was Fatima Lakhani writing for? I would’ve asked her had I been able to reach her. My calls to numbers listed along with public records under her and her son’s name went unanswered. I couldn’t reach her daughter either, nor did any of the cardiologists who wrote forewords to the book respond to my multiple requests for comment. I’ve gathered, from the lack of any public death records, that she’s likely alive, though her husband appears to have passed. Azizuddin Lakhani died in January 1998, aged 62, and he is buried in Hollywood Hills. There is no listed cause of death.

In the absence of clarity, I found myself fighting a temptation to graft my own family’s experiences onto Lakhani’s. My father’s heart didn’t recover for long, battered by the eventual installation of a pacemaker, then by heart blockages and lung cancer. He died last June. The experience of losing him has been so alienating that there’s a perverse comfort in believing that a stranger who filled a crucial gap for my family for years may have had a coda as senseless as ours.

If I had the chance, I would ask Lakhani if she and her children experienced my family’s same disenchantment with a regimented, seemingly health-conscious lifestyle. I wonder if Lakhani felt she did enough, how much weight and importance she put on the food they ate every day at home. I wonder if she would’ve written the book differently. Maybe she would’ve gone easy on the margarine. Maybe she wouldn’t change a word.

In the year since my father’s death, my mother and I have tried to triangulate where he went wrong, or whether he just got dealt a shit hand in life. We knew other people who’ve smoked for years, we’ve said, and they’re still alive and kicking. Following the instructions in a cookbook can’t shield someone from a body that’s conspiring to destroy them. But I wondered if the book’s recipes carried Lakhani’s family through its roughest patches in the same way it did for us, as a form of palliative care.

After my father’s death, my mother realized she couldn’t stay in the apartment where she’d last lived with him, so she decided to move, which required downsizing. “Was he a hoarder?” she asked me one Saturday in April, piling books into a cart we wheeled to a book drop near her apartment. I hadn’t realized that Indian Recipes for a Healthy Heart was in that pile. Once she’d settled into her new apartment, I scanned her bookshelf looking for it. I asked her why she threw the book out, telling her I wanted to write about it. She was only keeping the essentials, my mother reasoned, and though she no longer needed it, someone else might.