The More I Won, the Bigger the Barriers I Faced

Sometimes being Black equates to isolation, the feeling of rarely fitting in. As a kid, I was shunned by other Black kids because I “talked white.” And white kids called me “crack baby” because my dad was never around. White adults said I was going to grow up to be “one of the good ones.” At age 9 while playing in the park I was beaten and abducted by two Chicago police officers and left to die in gang territory.

But a summer day in 2001 changed my life. I found me. My neighbor let me ride his pink Pinarello Montello around the neighborhood. I only heard the drivetrain as I turned the pedals and the world whizzed by. I had no idea how downtube shifters worked, so rather than stopping to figure it out I pedaled harder with each lever click. My hands moved from the brake hoods to the drops and I broke the sound barrier. My mind tells me this was the fastest I’ve ever ridden. I was liberated.

Ten minutes into the ride I was stopped by the Chicago police, accused of stealing this beautiful Italian machine. Their reason: You’re riding like you stole it. My response: I finally understood happiness. Of course I was going to ride like I stole it. I’d discovered real freedom, and no one could take that from me.

As a teenager, I raced against white kids riding Dura-Ace and aero wheels while I was relegated to a badly assembled and overpriced aluminum Felt F50 that a shady shop owner let me work off over a year for $4 an hour. I won the first race I entered. I followed advice commonly shouted at races. I only looked forward, never back.

The wins mounted, but obstacles grew larger and the disparities were greater. Junior World qualifiers didn’t matter because powerhouse teams from the West rode with robotic efficiency. No local program wanted a Black kid from the South Side of Chicago. I learned that upgrade points and junior and elite state titles didn’t matter. Several USAC Talent ID camps meant nothing. USAC officials claimed I wasn’t ready to compete for a national title, so I didn’t. I found myself isolated again, but this time I had my bike. I still had my identity.

In 2011, I was one of four Black people graduating with a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Seldom did I see anyone that looked like me in my classes, and the workplace was no different. My last employer touted me as their diversity hire and I spoke to inspire kids who grew up like me. That same employer told me that I was not allowed to present new products to the media because I did not fit the image they wanted to put forward as one of their engineers. I continued to improve and waited seven years for an opening at my dream job. I am the first Black engineer at SRAM, but far from the last.

The cornerstone of the Black experience in America will always be rooted in a quest for identity, a quest that requires you to unearth that sense of freedom and build the resolve to fight for it until your last breath. The bike is my vessel. I now live sure of myself, connected to the world, and free. Free and breathing for those who have given their last breath.

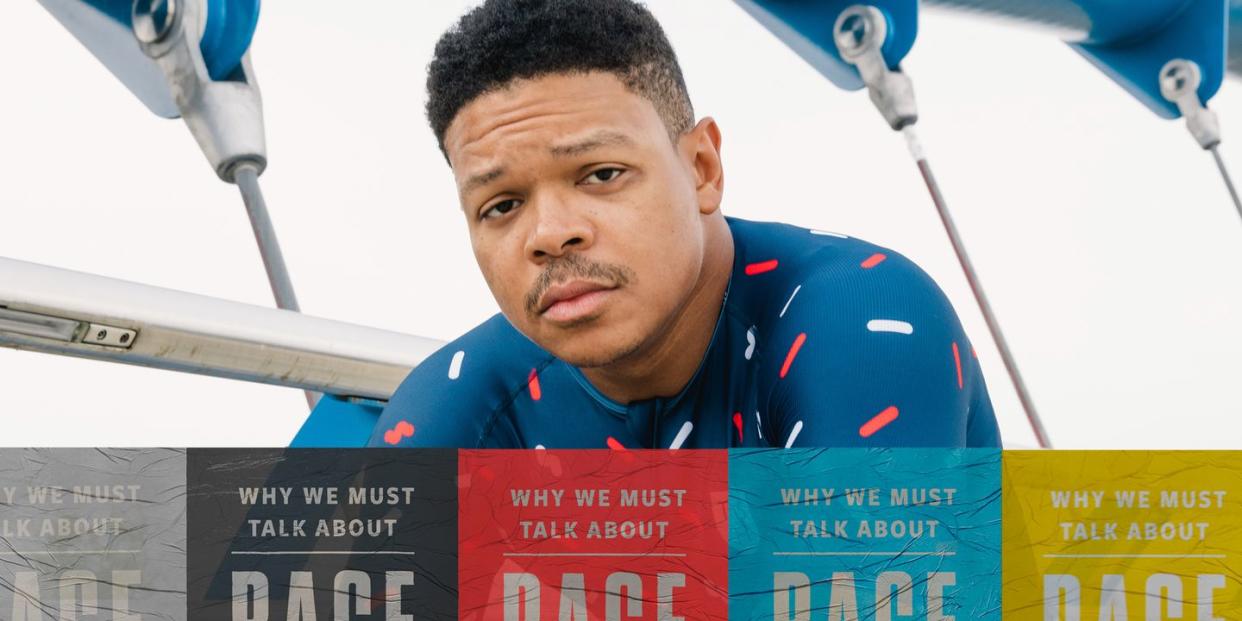

Sean Hopkins, 32, is a product development quality engineer at SRAM.

More Stories from Black People Who Love Bikes

You Might Also Like