Sculptor Mia Fonssagrives Solow Talks About Art, Fashion, Family, and Fembots

“I’m an old emerging artist,” jokes Mia Fonssagrives Solow when we meet about a week before her new show, Robots/Femmebots, opens at Findlay Galleries in New York. We’re in a space she calls her “holding area,” surrounded by her creations: robot-like sculptures, some of which stand about six feet tall. Despite being made of heavy metals, they exude personality—as does their charming maker, whose real-life story beats any fictional plot, sci-fi or otherwise.

Though Fonssagrives Solow has been working on these sculptures for only about 10 years, she has a lengthy artistic pedigree. She was raised among creatives: Her father, Fernand Fonssagrives, was a photographer; her mother, Lisa Fonssagrives, a famous model in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s; and her stepfather was none other than Irving Penn. (Penn and Lisa Fonssagrives met on a Vogue shoot in 1947; they married in 1950 after the model’s divorce.) And in the 1960s, Fonssagrives Solow co-owned a fashion house in Paris with designer Vicky Tiel, called Mia & Vicky, which was backed by Elizabeth Taylor (among others). Today, she’s constantly customizing her clothes. “If I see something I like, I know I have to totally change it.” That could mean adding embellishment to a Prada raincoat or making dresses from Hermes scarves. “The fashion brain never stops, never stops. It’s always there,” she says.

The robots came about when she found herself housebound during a blizzard. Unable to dispose of the garbage or recycling (pickup services had been suspended), she began repurposing the materials that were accumulating: eye-drop caps and empty glue bottles, Tea Forté containers, discarded circuit boards, Kleenex boxes, Tide containers, and a lone swim flipper. Once assembled, she cast the patched-together structures in metal, and the originals melted away. With its repurposing of discarded materials, it’s a process that speaks to current, serious themes of sustainability, but Fonssagrives Solow sees comedy in her creations as well: “My robots are humorous,” she says.

Among the people who have inspired the artist’s creations and make, albeit disguised, cameos in the new show: Lisa Fonssagrives (wearing Christian Dior and Elsa Schiaparelli), Irving Penn, a Bond Girl, the architect Peter Marino, and Madonna in her Jean Paul Gaultier cone bra—a cast of characters that reflect her rich and varied life. Here the artist walks us through some of the experiences that have had the greatest influence upon her.

When did you first discover your artistic calling?

At Dalton in sixth grade. My father and Dick Avedon shared a studio. When I finished school, I would go to that studio and they’d give me the leftover paper from the photo shoot, and I would paint or draw these houses that were black with teeth in the windows. I got kicked out of the art class for painting these bizarre images. The art teacher said, “This is disturbing for the other children. Maybe you should take something else.” She said, “Take shop. It’s only boys, but you’ll be fine.” I loved it. At the end of the class, I brought home a box that I’d made to give my father for his correspondence. And then I made a stand for Irving [Penn] to put his shoes on, because he’d pay me a quarter for polishing them.

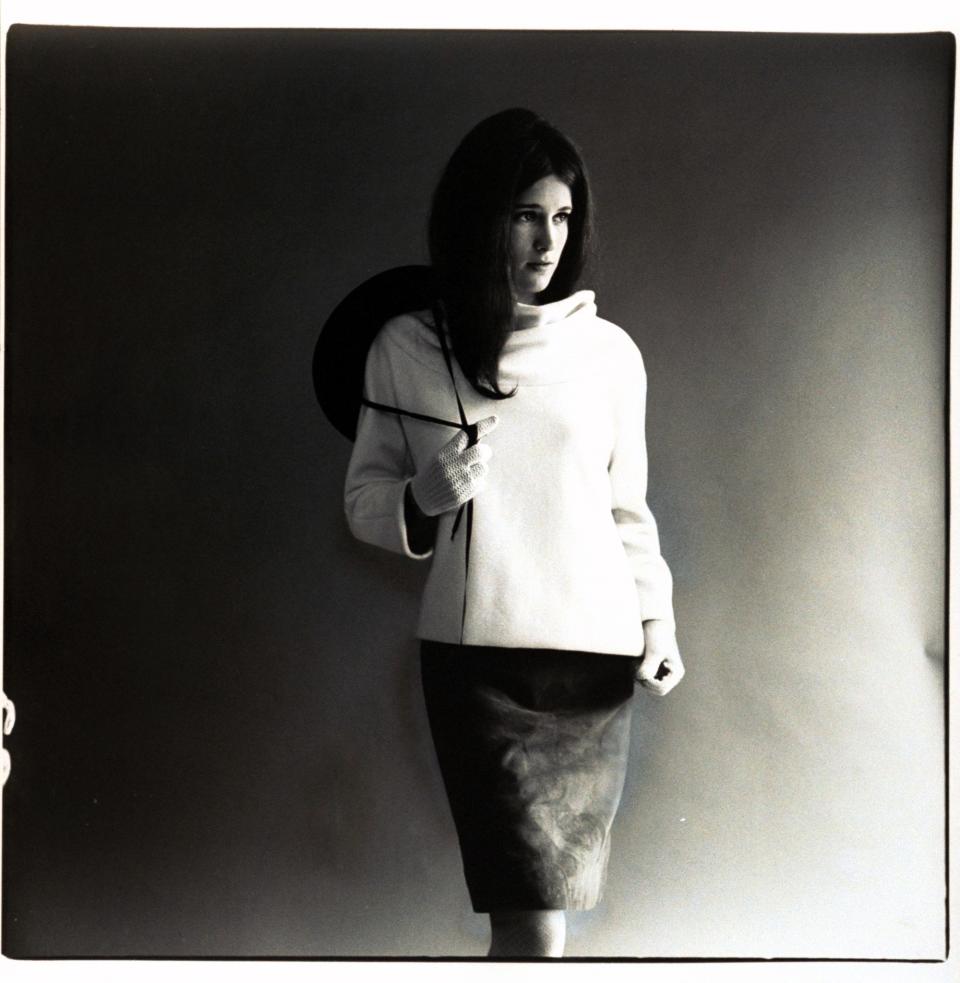

Vogue 1950

What were your parents like?

My mother taught me everything—how to ride a horse, how to take care of horses. You know, you don’t graduate from school in Sweden if you can’t change a tire. My father was very bohemian. I mean, if there was a hurricane, we’d get in the Studebaker and drive out to Montauk to look at the waves. Nature was his great passion. We would dive for mussels and then we’d cook them: That was called living off the land. We didn’t have much money.

Then Irving came into my life, and he taught me to have a rigorous work ethic. My father did not have a work ethic. It was just joie de vivre. Irving had a rigid work ethic: You go to work at eight and you leave at five and you leave your work behind. It was always like that, no matter what he was doing. It rubbed off.

Vogue 1964

When did you discover fashion?

I went to an all-girls boarding school [after Dalton]. In the brochure it said, “Give your child a clothes allowance so they can make something to wear on the weekends.” When I asked my mother about it, she said, “Here’s a piece of fabric; sew yourself whatever you want.” So I lay down on the floor, and I made a shape and I sewed it together. I was terribly proud when I finally got it right. I think I was 12 at the time.

lfp

Out on the farm in Huntington [the Penns’ country residence], we’d have breakfast and then everybody went to their work. My mother was painting at the time, Irving was doing platinum prints, I had the sewing room to myself, and my brother Tom was welding. Every day, Irving would say, “What are you going to do in life? What are you going to be?” It was a question that drove me nuts. At 13, I didn't have an answer, but he expected an answer.

Farm House of Irving Penn and Lisa Fonssagrives Penn, Vogue

I started making dresses for my mother, and my mother would wear them, and then her friends would buy them for 35 bucks. I used these beautiful flower prints that looked very much like what Pucci would end up using. So I thought, Okay, now I know what I’m going to do—I’m going to go to Parsons. I got a part-time scholarship, and then I worked all summer to pay for the rest. As soon as I learned to make a sleeve, I could charge more for the clothes.

Fashion Designers with a Dog

Can you tell us about meeting Vicky Tiel and starting your fashion business?

Vicky and I became friends immediately at Parsons. If someone told us, “That’s how you shouldn’t dress,” we thought, This is how we should dress. But we’re very, very different. After Parsons we did this fashion show and Eugenia Sheppard [the New York Herald Tribune’s fashion journalist] wrote about it. And then we went to Paris.

We took a boat over with everything: our sewing machines from school, her dog, my skis. I had an assignment from Sears and Roebuck to report on what was going on in Paris, and Vicky went there with $250 her dad gave her. The first year, we were eating very little. I would buy an egg and Vicky would buy two cigarettes. Vicky spoke French, but I didn’t because we spoke Swedish at home. (My father was French, but he spoke Swedish.) So I didn’t speak French, but when we got to Paris, I discovered I had a carte d’identité, which you needed to own a building, to do any work, to start a business.

We found a space in the building of Madeleine Castaing on Rue Bonaparte. I was in charge of renovating it—the material, hard things—and Vicky was in charge of pillows and mirrors and what’s called the flou. We had $50,000 from a deal we’d made to sell our story to Paramount, and Elizabeth Taylor gave us another $50,000, which we paid back after the first year.

Richard Burton & Elizabeth Taylor at Paris Fashion Week, Sunday 21st January 1968.

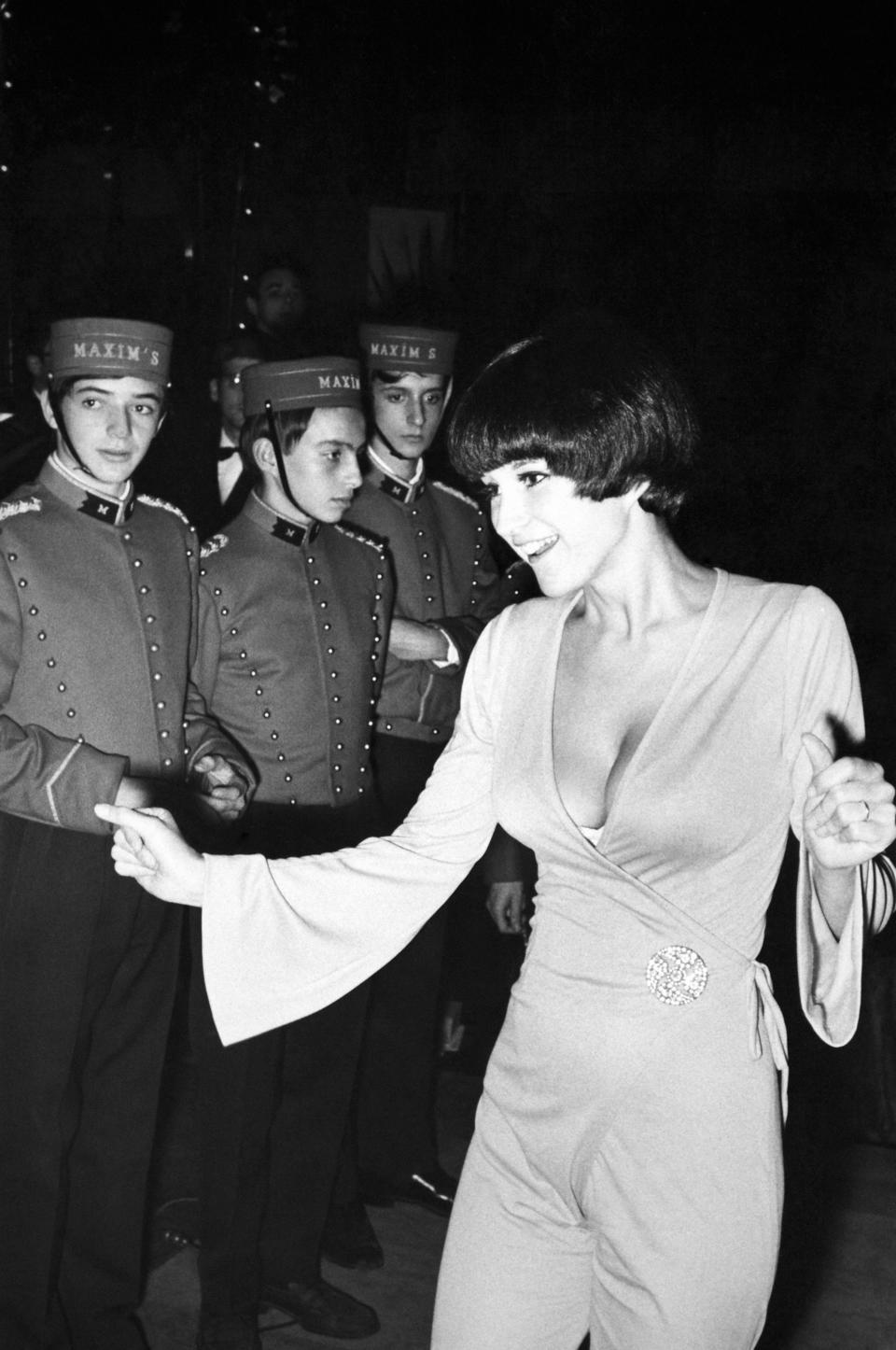

What was Paris like then?

Paris in the 1960s was heaven. In Paris, everything is soft corners. You can go and have a cafe au lait any time of day; you can go at midnight and have oysters. I wore miniskirts and had my hair long and brown and wild. In your 20s you can do that. My hair turned white after an appendix operation I had later in my 20s. I had come back to America, and my mother knew Mr. Kenneth [Battelle, the hairdresser who did Jackie Kennedy’s hair], and he said, “Mia, you can have your hair long and wild, but it has to look elegant. There’s nothing worse than a gray-haired witch. You must keep it kempt.” So I said, “Okay, Kenneth. Let’s cut it so it looks kempt.” And he did.

Anniversaire des 75 ans du ?Maxim's? à Paris

So you’re running around Paris with your beautiful hair and your miniskirts. What’s next?

And then it was enough. Vicky fell in love with the makeup artist for Elizabeth [Taylor], and I married Louis Féraud. I was getting into my late 20s, and I thought, I really want children, and he wanted to go paint in Tahiti, and I wanted to learn woodworking. So we delicately disengaged. I went straight out to California and decided I would stay there. Vicky got upset, but it was a blessing in a way for her, because I just said, “Keep it all.” She loved these frilly, beautiful evening cocktail dresses. And I’m science-fiction. The business didn’t need two people. [So Mia & Vicky became Vicky Tiel.]

I learned woodworking in a shop in Topanga Canyon where there was a family of boys that built furniture. They showed me how to work with the heavy machinery, and they let me use the shop at night when they were finished. I made huge pieces. When I came back to the East Coast, I met my husband, [Sheldon Solow], and we went on a trip to Greece, where the Cycladic pieces really impacted me.

Is sustainability something that you think about?

Constantly. We’ve destroyed the earth as we know it. But my art isn’t going to sustain either; it’s not going to survive what’s coming.

Sculptor Mia Fonssagrives Solow Talks About Art, Fashion, Family, and Fembots

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

“Robots/Femmebots”

And how have you organized the current exhibition?

Well, there are humorous, dysfunctional robots. We have so many busts of Caesar, Caligula, and all of those guys. I thought, I’m going to make busts of some of the people that I like. There’s also a sculpture of Madonna, in her Jean Paul Gaultier bronze bra. (It’s made from the tops of my eye drops.)

How would you describe your bots?

They’re not robots that do anything. I mean, I would love one of them to bring me breakfast. They do have personalities, and they all have names. My robots are humorous ideas of what robots could be, instead of the fearful kind of robot that’s going to take over. The fembots also show the power and strength of women. There are even some sculptures of my mother. She was one of the original fembots in my mind.

Robots/Femmebots is on view at Findlay Galleries from September 12 to October 12.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Originally Appeared on Vogue