What Scottie Pippen Taught Me About the American Dream

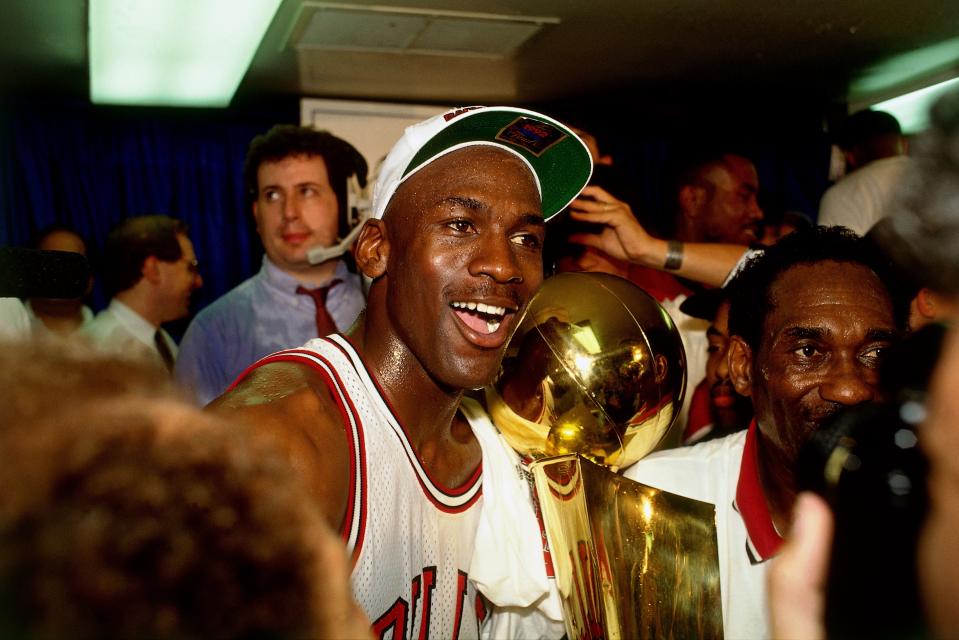

When I was in middle school, I taped up a poster of Michael Jordan in the bedroom I shared with my younger brother. The photographer had caught him mid-flight, like a regent astride an invisible horse. He looked all-powerful. He looked sublime. For us, he became the epitome of individual greatness. This was Atlanta in the ’90s, but we weren’t really fans of the Hawks. Yeah, they had Dominique Wilkins, but they didn’t mean anything to us. Not the way Jordan did. Across the room was our only other poster: a villa at sunset, three sports cars in the garage. Other visions of the good life hung on the walls of our family’s imaginations: for Mom, a red Mercedes; for Pops, a beach house on Martha’s Vineyard. My parents had fled unrest in Ethiopia in the early 1970s, becoming part of the largest-ever voluntary influx of Africans to America. For a family like ours, post–Civil Rights era America offered the promise of self-actualization, and Jordan became a symbol of that promise, a figure whose greatness seemed to transcend race and debate. We felt we could channel his power and make it our own.

In those years, even when I met with adversity, I’d latch onto the Jordan legend. After all, the greatest basketball player of all time did not, at first, make his high school team, so there was no shame in getting cut from the J.V. squad of the Walton Raiders. If I could do better on my SATs than on my PSATs, then I would still get into Harvard. Our parents nodded along, and even if they didn’t quite share our enthusiasm, they stoked the fires of our success with two fresh pairs of Jordan 6s one Christmas. I can still feel the give of the little spring-action clamp that held the laces at the tongue. Tightening that clamp made me feel ready for flight.

You grow up, of course. Dreams of playing professional basketball, or even high school basketball, are deferred. You learn life’s not as simple as being excellent and working hard. You hear your parents’ stories about being undervalued at work, Mom’s coworkers at the bank becoming her bosses, real estate agents refusing to show Dad a house, never mind the ones on Martha’s Vineyard. You do a good enough job on your SATs, but not Harvard-good. As a young adult, you don’t get the fancy magazine internship. For a while you become a paralegal, then an adjunct professor going from school to school. You’re passed over for promotions yourself, paid less than you’re worth, offered stiff smiles at open houses. You have a family of your own to support. You grow up, in other words, and recognize that your story hewed much closer to that of the man who stood at Jordan’s side.

As we’re reminded by The Last Dance, the epic documentary about the Chicago Bulls’ 1997–98 championship run, Scottie Pippen was the most underappreciated part of that team. They were dominant, fearsome, stylish—the epitome of the roaring ’90s—and I remember them so well; I can still see Jordan draining a cold-blooded dagger of a jumper over Bryon Russell to clinch that ’98 ring. But I struggle to recall Pippen’s presence, his storyline, his anything. I didn’t save up birthday money for his shoe, though Pippen’s 1996 Air More Uptempo remains one of the baddest Nikes ever. I have kin who resemble Pippen with his big Ethiopian-looking eyes, but none of them tried to emulate him in our pickup games the way my uncle, a trim man with a shiny mahogany pate, would channel Jordan as he dribbled around our backyard court, his tongue clenched between his teeth.

Born in tiny Hamburg, Arkansas, the youngest of 12 children, Pippen grew up playing on a dirt court at his grandmother’s house to escape the psychic weight of his family’s hardships. Both his father and brother were wheelchair-bound before Pippen was in high school. “I felt like I couldn’t afford to gamble myself getting injured and not being able to provide,” Pippen explains in The Last Dance. “I needed to make sure that people in my corner were taken care of.” Those circumstances compelled him to sign a longer, safer, and lower-paying contract with the Bulls at the end of the 1991 season—one that Jerry Reinsdorf, the Bulls’ owner, famously refused to renegotiate, even as Pippen’s stats and the NBA’s revenue exploded. As a player, he would reimagine the point-forward in a way that paved the way for such multi-faceted superstars as Kawhi Leonard. Yet he became one of the most exploited players in NBA history—the 122nd highest paid player in the league at a time when he was indisputably one of its best, perhaps second only to Jordan. “My day’ll come,” we hear Pippen say in archival footage. “My day will come.”

In episode two, we hear Jordan call him Pip, and there’s more than a touch of the Dickensian to his hardscrabble beginnings and great expectations—a journey that deserves its own epic treatment. After leaving the Bulls at the end of the ’97–98 season, Pippen played for the Houston Rockets and the Portland Trail Blazers before coming back to Chicago for one final year. In retirement he was ripped off by a financial adviser who was later sentenced to three years in prison. Just before this year’s NBA All-Star Game, Pippen said on an episode of the Thuzio Live and Unfiltered podcast that in 2019 he’d been fired from his role as an ambassador for the Bulls after they couldn’t reach a compensation deal. After all the financial turmoil he’s been through, you’d expect a note of bitterness in his voice, but in his interviews for The Last Dance, the man doesn’t look a day over 40, his body lean, his skin glowing, his voice as soothing as a late-night deejay’s. He owns a farm back in Hamburg and appears regularly on NBA TV as a commentator. Scottie seems okay.

My folks seem okay, too. When my brother and I were tiny, they’d made a reverse Great Migration from Boston to the South to start their own small businesses. Though Mom never got a red Mercedes or Dad a house on Martha’s Vineyard, they’re still living in the suburbs outside of Atlanta, both semi-retired. Pops sold his gas station, and Mom still runs her travel agency remotely during quarantine. Whatever the American project was, they seemed to understand that it would never make room for their dreams. But at least they could build walls around ours.

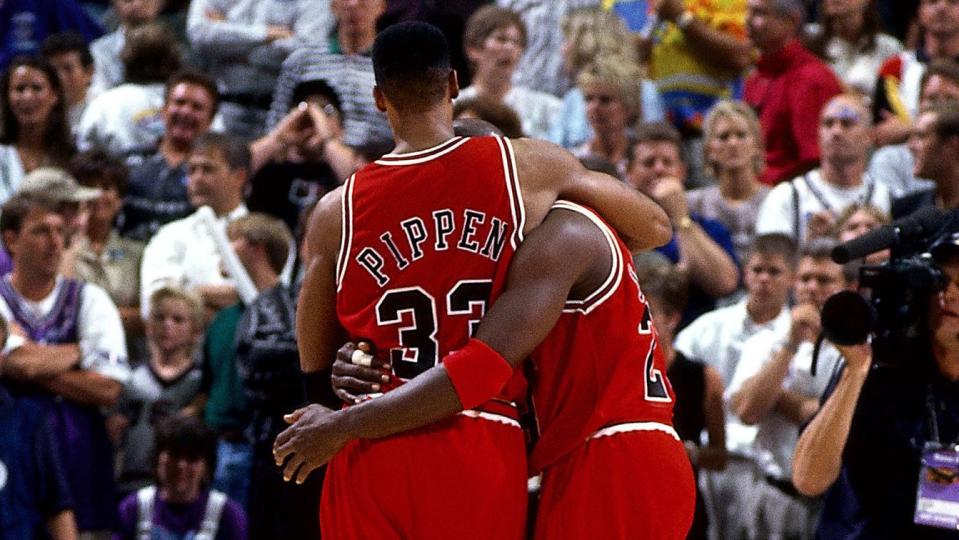

pippen-holding-up-jordan.jpg

My childhood bedroom has long ago been redecorated; Jordan came down after I fled the South for college. I’m too old for posters now, but if I were to hang something on my bedroom wall today, it would be a different image from those ’90s Bulls. Instead of Jordan soaring through the ether, I’d frame a still from Game 5 of the 1997 NBA Finals—the mythic Flu Game in which a seriously ill Jordan somehow still managed to drop 38 points. The portrait I have in mind has another cropping, though. Pippen is at its center, Jordan’s arm hanging limp around his waist. To hear Scottie tell it years later, Jordan was so disoriented that game that “He didn’t know what he was doing or what was going on.”

Pippen had a characteristically reliable night—17 points, 10 rebounds, 5 assists. But his indelible contribution was embracing Jordan, not always the most compassionate teammate, in his rare moment of vulnerability. That’s how I like to think of him: walking down the court, propping up the bulk of Jordan’s body, the hero of a quieter epic making sure, as always, that his brother did not fall.

From the stone-cold classic to the low-key underrated to the…well, less-than-GOAT, we're ranking the greatest basketball sneaker line in history.

The new king of Sunday nights takes a break from editing the final episode to talk MJ, that former Chicago resident, and trying (unsuccessfully) to stay off Twitter.

Originally Appeared on GQ