Sci-Fi Author Ted Chiang on Our Relationship to Technology, Capitalism, and the Threat of Extinction

In 2010, a small book lit up the world of science fiction, then disappeared. Very few people have even read it.

The Lifecycle of Software Objects told the story of two people raising primitive AIs—think Neopets, except with the temperaments of precocious children—and captured the ongoing debate around artificial intelligence in vividly human terms. The book won a Hugo award for best novella, then, nearly as soon as it came out, ran out of print. Lifecycle became a holy relic for sci-fi readers, with copies surfacing rarely, sometimes for hundreds of dollars. It was nearly impossible to read, at least until now.

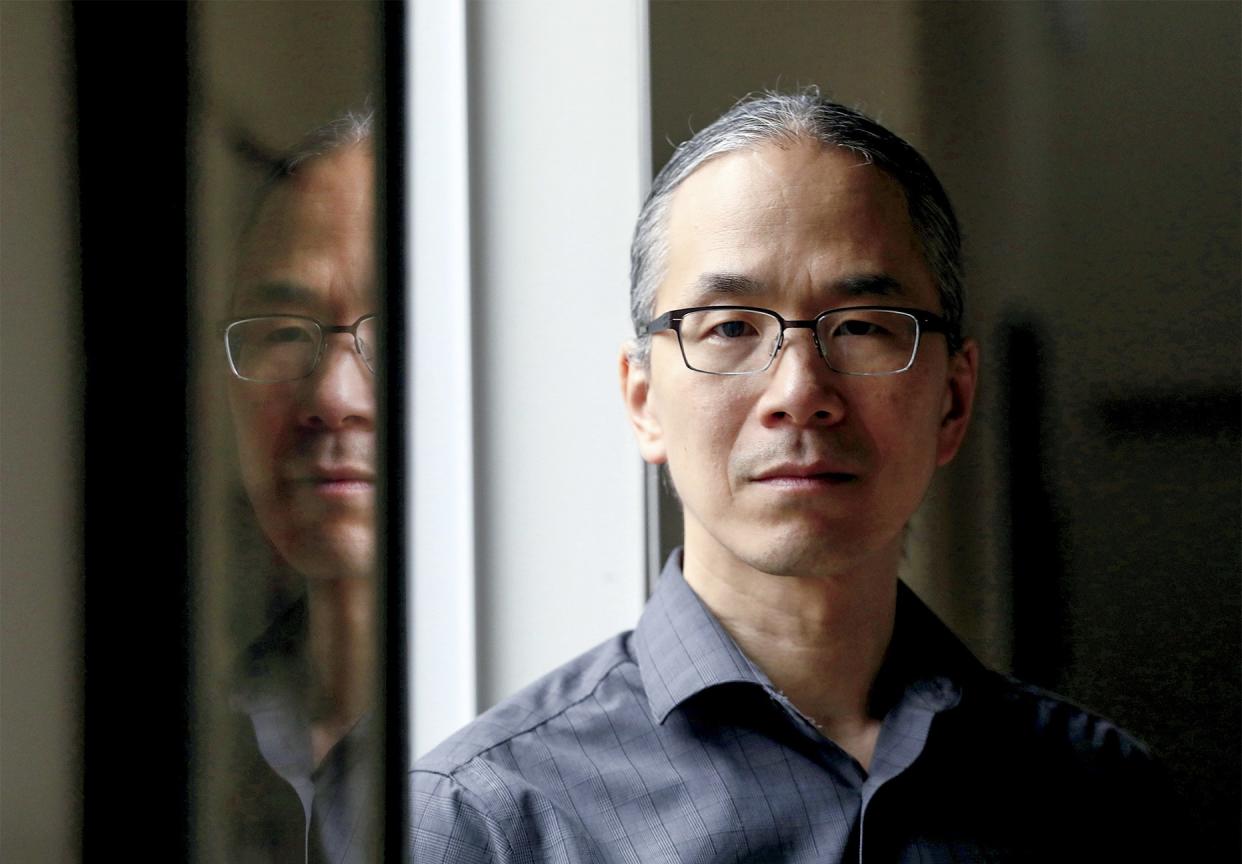

Ted Chiang's new book of short stories, Exhalation, is his first collection since 2002. Already a legend in the sci-fi world, Chiang has a visionary knack for turning scientific discoveries and technological innovations into broader diagnoses of the human condition. Best known for “Story of Your Life,” which inspired Denis Villeneuve’s Oscar-nominated Arrival, he has a relatively small body of work that trickles out slowly. He holds onto stories until they’re just right. (He once refused a prize nomination because he felt the story had been rushed and didn’t meet its full potential.) And, as Lifecycle can attest, when they do appear, they can vanish just as quickly. In the past 28 years, he’s released 17 short stories and novellas. A third of them have taken home Hugo and Nebula awards, science fiction’s highest honors.

Exhalation collects Chiang’s nine latest stories, which, like “Story of Your Life,” explode our notions of time, language, and free will in ways that will keep you up at night. “The Lifecycle of Software Objects” returns to consider our ethical obligations to AI. “The Great Silence” wonders where we’re going as a species, while “The Truth of Fact, The Truth of Fiction” explores how our self-image will change once we can record every second of our lives. Two stories appear for the first time: “Omphalos” suggests that maybe God exists but has placed his attention elsewhere, and “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom” explores the ways our behavior would change if we could communicate with alternate version of ourselves. If anything can be said of Chiang, it’s that he likes big, thorny questions.

From a book tour on the west coast, Chiang agreed to swap some emails about his new book and the role technology plays in our lives today. He shared his thoughts on social media, capitalism, and why science fiction may be more urgent now than ever.

GQ: These stories cover a fairly long period of time. The oldest, “What’s Expected of Us,” was first published nearly fifteen years ago. How have your interests evolved over that time? What are the most significant ways you feel our culture’s relationship with technology has changed in that time?

Ted Chiang: I think my interests have remained fairly consistent over time; themes like free will and the relationship between language and thought were visible in my first collection, and they’re visible in Exhalation as well. As for our culture’s relationship with technology, I think the biggest change has been the rise of social media. We’ve essentially given every individual their own television network, and we’re still trying to understand the ramifications of that.

What are those ramifications, or at least the most important ones? Are there any you think people don’t consider enough?

I think the big issue is the lack of editorial oversight, and to what extent that’s a feature or a bug. It seemed like a feature during the Arab Spring uprising, when social media allowed breaking news to be disseminated far more rapidly than traditional media outlets could. But now any neo-Nazi or conspiracy theorist can reach an audience of millions and make a fortune from advertising revenue in doing so, and the social-media platforms just shrug. I don’t want to romanticize the days when there were only three broadcast television networks, but at least it was harder to get hate speech on the air. We’ve created technology that gives everyone a megawatt transmitter without giving them a standards and practices department.

Some critics have suggested that Exhalation takes an optimistic position towards science and technology. When you look at how our culture interacts with technology today, what gives you reason for optimism? For concern?

Optimism is relative. I try to look at both positive and negative aspects of new technology; if you are used to hearing only about the negative aspects, an approach like that will come across as optimistic. By contrast, if you are used to hearing only about the positive aspects, then that approach will seem pessimistic.

Right now I think we’re beginning to see a correction to the wild techno-boosterism that Silicon Valley has been selling us for the last couple decades, and that’s a good thing as far as I’m concerned. I wish we didn’t swing back and forth from the extremes of Pollyannaish optimism to dystopian pessimism; I’d prefer it if we had a more measured response throughout, but that doesn’t appear to be in our nature.

What does that more measured response look like? Any specific examples of people or institutions that strike that balance well?

I generally like Jaron Lanier’s approach to technology. [Ed. note: Lanier is a computer scientist and author best known for his book You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto.] He’s been a pioneer in various aspects of the computer industry, so he’s anything but a technophobe, but he’s also been consistently skeptical about the more extravagant claims made about digital technology.

“The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling,” a story about life-logging, or using technology to record every second of our experience, raises interesting questions about the way tech can quite literally change the way we think. Do you see that happening at present? In the near future?

I think digital technologies have the potential to affect our cognitive processes as much as the invention of writing did. There’s some debate about exactly when it became common for people to read without moving their lips, but whenever it happened, it signaled an important transition: written words shifted away from being just a representation of speech and toward being a different mode of thinking. I think digital technologies could take on a similar role. We can’t predict exactly what the impact of that will be; it will probably only be visible in retrospect, the way that the impact of literacy was.

That same story also had me asking questions about data ownership. There seem to be parallels between life-logging and the ways people use social media today. Is that a subject that interests you? Do you envision people’s relationship to their personal data changing in the coming years?

There are two separate issues here. One is whether it will help you to have a lifelog, a digital record of everything you do. The other is whether you want your lifelog stored on corporate servers where it’s used to sell you things. In theory, it’d be good if we could engage with the first question on its own. In practice, it’s hard to separate the two. It’s related to a question someone asked me recently about whether it would be a good thing to have a digital assistant making some of your decisions for you. One could decide it’s okay to have a computer help you with your decisions without wanting Amazon to take that role.

That doesn’t seem like a decision that’s available to many people today, though—to use a lifelog or a digital assistant without having your personal information used to sell you stuff. Or is it?

No, and that’s exactly the problem. This is an example of a larger issue, which is it is hard to separate the threat that technology poses from the threat that capitalism poses. In the early days of personal computers and the internet, we were focused on the potentially transformative or liberating aspects of the technology.

What we didn’t anticipate was how the technology would be used against us by giant corporations. For example, everyone thought that we’d have a micropayment system by now, but instead we’ve wound up paying with our personal data. It’s not impossible that the ship will change course, but it’s going to take a while.

“The Great Silence” is a short but powerful story about parrots, intelligent life, and the Fermi Paradox—which I found fascinating. Could you explain what drew you to it?

The Fermi Paradox refers to the apparent contradiction between two things: the first is that, by even the most conservative estimates, the universe should have given rise to intelligent species many, many times, and there has been plenty of time for any one of them to traverse the galaxy. The second is the fact that we have not seen any signs of extraterrestrial intelligence.

I’m not sure when I first learned about the Fermi Paradox; it might have been from watching Carl Sagan’s TV series Cosmos as a child. When [visual artists] Allora & Calzadilla approached about collaborating, they wanted to draw a connection between the radio telescope at Arecibo and Puerto Rican parrots, who are nearly extinct due to loss of their jungle habitat. I thought that the Fermi Paradox offered a way to connect these two, because it’s been proposed that intelligent species go extinct too rapidly to leave a mark on the galaxy.

So intelligent species burn out too quickly to make intergalactic headway—I have to ask, do you think that’s what will happen to us?

I don’t know. We used to think that the biggest threat we faced as a species was nuclear war. Now it looks like it’s global warming. If we survive that, it’d be tempting to think that it’ll smooth sailing afterwards, but any consideration of this question is primarily a reminder of how much we don’t know.

So you were a fan of Cosmos as a kid. Did any specific episodes leave a particular impression?

I can’t remember the individual episodes, but there are certain sequences that stick in my memory, like the animation illustrating the evolution of life from a single-celled organism to human beings, and the one showing the movement of stars over millions of years. I can still remember the music accompanying those animations. More generally, Carl Sagan’s work, in Cosmos and in other books, played a big role in shaping my understanding of the universe.

Ian McEwan’s novel Machines Like Me has renewed conversations about the relationship between science fiction and “literary” fiction. Are genre distinctions something you think about?

I definitely think about genre distinctions, simply because for the vast majority of my writing life I didn’t have the option to not think about them. Things are changing now, which is great, but a lifetime of experience isn’t forgotten in an instant.

I think there are a couple reasons that science fiction is more respectable now: one is that we are living such in a technologically saturated world that any fiction ignoring the role of technology in our lives feels out of touch. A related one is that the modern world has become just so damned weird; if a novel accurately describing 2019 had been published in the 80s, it would have been considered satire. Many people have said that contemporary realism isn’t up to the task of depicting contemporary reality, and I think there’s some truth to that.

I realize “responsible tech use” is a fairly big and abstract concept. What does that mean to you?

Broadly speaking, I think it means applying to our use of technology the same ethical principles we use in life as a whole, which means respecting other people’s preferences the way you would like them to respect yours. For people working in technology, that might mean asking the question, would you personally want to use the product you’re selling? (Note how many parents working in tech try to limit their children’s use of tech.) Similarly, when a tech company tries to disrupt an industry, it might be worth asking, are the jobs you’re creating the kind of job you’d be happy doing?

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Originally Appeared on GQ