Scatter My Ashes in the Rocky Mountains

This article originally appeared on Backpacker

We were on a family hike in Rocky Mountain National Park: me, my wife, our son Jake and his partner Lisa, and our younger son Tyler. It was a bluebird day, and we headed up the Colorado River Trail on the west side of the park. It threaded through a tranquil valley shaded by pine and aspen, but flowering meadows provided sunny breaks. Best of all, I was surrounded by my beloveds. That's when I suddenly started thinking about death. Particularly, my own.

When my dad died, I found a beautiful final resting place for him in the Conway, New Hampsire cemetery, with Mt. Chocorua looming above. My dad was my original hike leader, and instilled in me a profound love of the mountains. It was an appropriate spot for his final rest stop.

That wasn't the original plan. My brothers and I had wanted to scatter his ashes on Mt. Washington, but my mom preferred a more traditional final resting place. Now her ashes are interred beside his in Chocorua's shadow.

As these things go, I'm next in line, and I have an idea in mind for my final hike, and rest stop.

I'm not a morbid person, but sometimes death forces the issue. A few months after the Colorado River hike, I was standing in a circle of relatives, all ages, after the funeral service for my mother-in-law. We were discussing our emotions and the degree to which we have access to them.

A few minutes earlier, I had been wiping away the tears that spontaneously spouted as I watched Jake and Lisa lay hands on the burial urn that carried the remains of his grandmother.

Until that moment in the service, I was able to focus on my mother-in-law's long life (98 years and change) and many accomplishments, but when these beautiful young people stepped to the front of the church, it brought to my mind a queuing metaphor of mortality: We're all waiting along a trail that snakes back from the graveside, like doomed climbers on Everest, roped together and shuffling to our final destination.

As life advances, so does your place on the rope line. And as you watch older generations stumble onto that ultimate summit, you anticipate the time when you'll make your last boot print on the way to oblivion.

Now that my mother-in-law is gone, there's one less person blocking my view of the inevitable. I thought ahead to the day my son and his partner will take my place in that pew, and I'll be in the urn, and there's nothing I can do about it.

That's when I started crying.

My personal rainstorm hadn't yet passed by the time we reached the funeral reception. I tearily commented that there had been a 40-year period--including my own father's death--when I hadn't cried at all. My niece asked me how I'd found the ability to cry again. I could tell her the exact moment: On the summit of Mt. Ida, on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park.

My dad was born in Massachusetts, an afterthought among five much-older siblings, but they regularly took their pipsqueak brother along for hikes in New Hampshire's White Mountains. My dad would marry and sire four sons, of whom I was the pipsqueak. He personally carried me up Mt. Washington when I was three, and I scrawled my name in the register at Zealand Falls Hut when I was five. My dad led us to all of the White Mountain huts when I was a kid, then I joined him to touch all 48 summits of New Hampshire's 4,000 footers. He was my uphill example, and it led to a lifetime of hikes for me, all around the world. I live in Colorado now because he set me on the trail that led here.

My dad was also the proto-jogger, lacing up his Jack Purcell tennis shoes to follow running pioneer Jim Fixx out onto the roads of our small Connecticut town. He continued on that running path until December 1996, when he stumbled on his regular running route, lowered himself to the ground, and died.

I know all that from a neighbor who watched it happen. A half hour later two cops knocked on my parents' door, and asked my mother, "Ma'am, do you know where your husband is right now?"

"He's out for a run," she told them.

By then he'd already crossed the finish line.

An hour later I was a newly bereft son driving north toward the home of my now-widowed mother, and saw a Batesville Caskets truck barrelling in the opposite direction.

I laughed bitterly at the irony, but I didn't cry. I hadn't relearned how to, yet.

Twenty years later, my hiking buddy Alan's wife, Sarah (I've changed their names for privacy), died of a stroke. Alan and I agreed that we'd climb to the summit of Mt. Ida, on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park, to scatter her ashes. Alan could see the summit from a cabin he and his late wife had built, so he would be reminded of her each time he looked north. We got together during the summer of 2016 to carry Sarah's ashes to their final resting place.

We were on the trail early, with two other friends, and hiked for several hours above timberline, where the views go on forever. We reached the summit, then clambered over rocks to find a sheltered place. This was a somber--and windy--occasion, and we wanted to avoid recreating that scene in The Big Lebowski, when The Dude and his mates end up dusty with cremains on a breezy oceanside cliff.

Alan and I are both literary types, so we came prepared with readings. I had Alfred, Lord Tennyson's "Crossing the Bar" at the ready. It was my father's favorite poem; a soloist sang a musical version of it at his memorial service, long ago. I set my jaw back then, and restrained the tears.

On top of Mt. Ida, I pulled up the poem on my phone, and read aloud:

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

And at that point I stopped, overwhelmed by emotion, and finally shed the tears that hadn't come twenty years earlier, when my dad died. Alan gave me a hug and offered a sympathy sob himself, at which point we both burst out laughing.

I said, through my tears, "I'm trying to help you through this, but I'm not exactly the Captain of Composure myself!"

More laughter, more tears, and then finally, the conclusion of the poem.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For tho’ from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crost the bar.

We cried and laughed through more readings, while our hiking buddies looked at us as if we'd lost our minds. Which we had, of course. We'd lost control, and concern for how we looked, for the snot dribbling from our noses or the way our faces reddened with emotion, and about the way tears streamed down our cheeks and were caught by the wind and swirled around us--sunlit jewels of grief taking flight.

That is when I learned to cry again.

We were breaking regulations when we released Sarah's ashes to the four winds. Rocky Mountain National Park is OK with ash-scattering, but it has very specific ideas about how you should do it. There's NPS Form 10-930s (Rev. 08/2021) to fill out (SPECIAL USE PERMIT SHORT FORM-SCATTERING ASHES) and the instructions that you avoid developed areas, and make sure you're 200 feet from any water source, among other things. Also: "Ashes should be spread about and not buried or placed in a pile."

If we committed a crime that day, though, it was mostly a victimless one. For backup on this, I called Jeff Marion, PhD, adjunct professor of forest services and environmental conservation at Virginia Tech, and one of the world's foremost recreation ecologists. I asked him if it is possible to adhere to Leave No Trace principles while scattering human ashes in a wilderness area.

"Absolutely," was the short answer. A relief, no doubt, to the three hundred grieving relatives who fill out that ash-scattering form every year at Rocky Mountain National Park.

"I've done lots of studies of human impacts on vegetation, soil, and trails," he continued, "but nobody has ever asked me to study human remains."

But he had an opinion.

"Human ash is completely clean: no diseases after combustion, and no ecological impact on the land. And I see no reason why there would be an impact on a large body of water."

Any positive impact?

"Ashes do contain a lot of micronutrients, almost like a light fertilizer. Volcanic and tree ash are related to huge growth spurts in plants."

There's a vision of immortality: Micronutrients, watered with salty tears, spurring on trees that will shade our children, and their children.

Last winter, my older son and I were in the car heading west on I-70, toward the mountains. He thought we were just headed for a carefree ski day at Winter Park. I had other ideas.

"Remember that hike we took with your brother, your mom, and Lisa," I asked him, "when we were on the west side of Rocky last year?"

He did.

"Well, your mom and I have been talking it over, and we've decided that, when the time comes, that's where we'd like to have our ashes scattered."

A pause.

"Wow, that took me to a place where I wasn't ready to go," he said.

Death is like that. But for the record, I'm always up for a trip to Rocky Mountain National Park--by car, on foot, or eventually, in an urn.

Now I know what I was missing during my 40 tear-free years: My emotions have finally reached the surface, and I feel them from my heart's core all the way out to my tear ducts. It's much easier to let them rip than it ever was to bury them deep.

I haven't run dry since, because there's so much in life that causes my emotions to overflow. I'm an equal-opportunity weeper, springing leaks while singing a beloved song, or reading a snatch of poetry that's important to me, or looking at a photo that makes the long-dead present to me again, or even when hiking along a trail that's too beautiful for words, with friends and family I love.

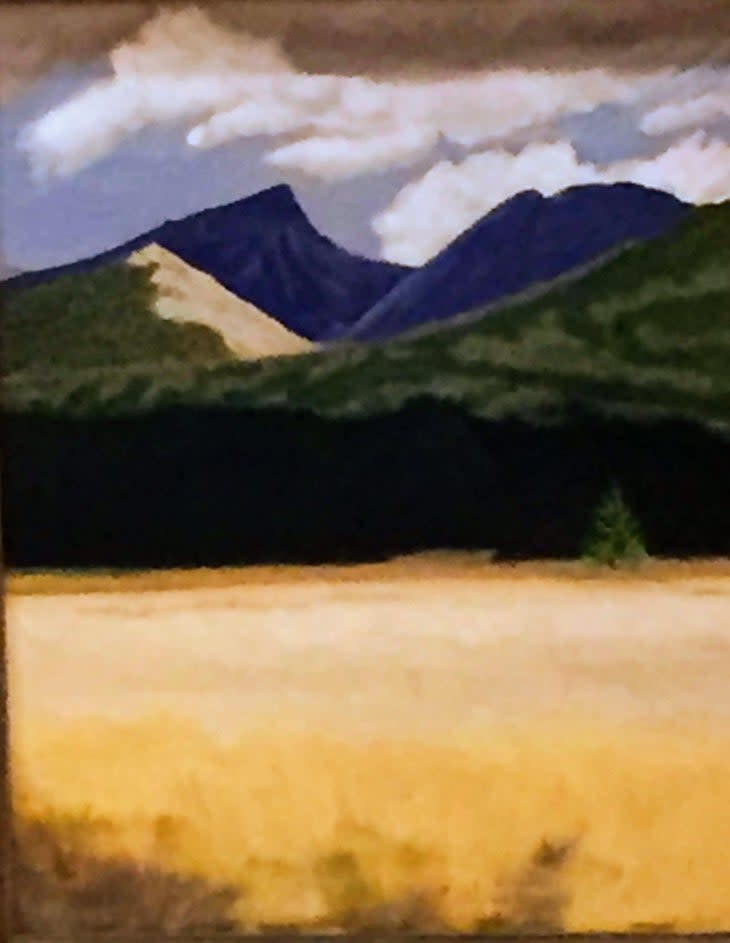

A year after our mountaintop sacrament, I had it in mind to paint Mt. Ida, as a tribute to Sarah, and to my long relationship with her grieving partner. After it was finished, I drove to Alan's house and handed this painting over, in memory of that day.

Life's journey has an end. Tears now lubricate my progression toward it. I'm so grateful that I climbed Mt. Ida and released the flood.

But next time, I promise: I--or someone I love--will submit the SCATTERING ASHES form.

No hurry. Some trips are better if you delay a bit.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.