Can USC Survive Scandal and Shed Its Spoiled-Kid Reputation Once and For All?

Each spring, when college acceptances and rejections arrive in the mail, a simple maxim applies: The thicker the envelope, the better the news. So when, in early 2015, a large box from the University of Southern California was delivered to her Upper West Side home, Susan Katz knew her son Will Berman would be excited

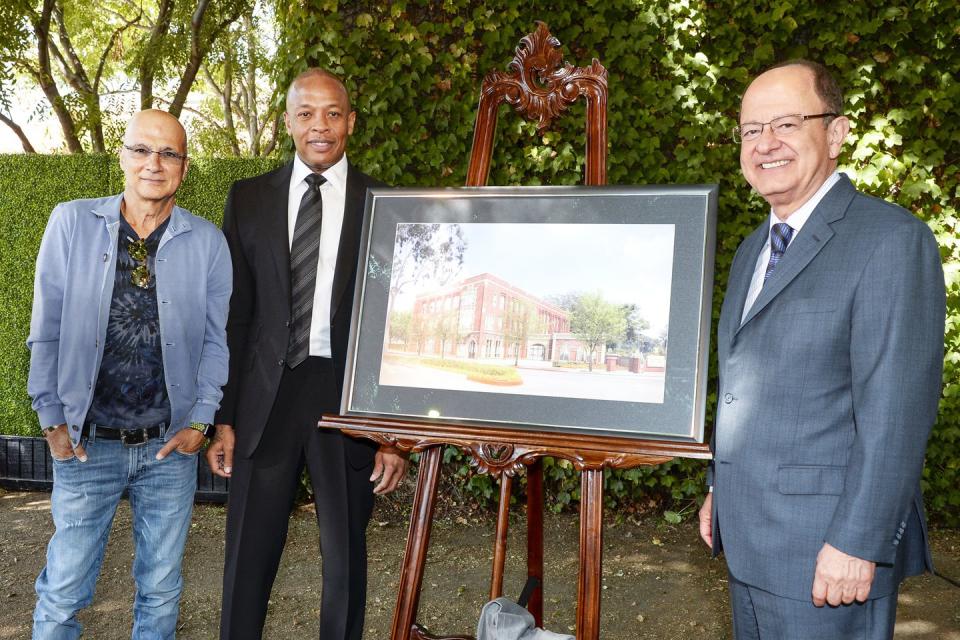

Inside was not a letter (one came separately) but a wooden jigsaw puzzle that Berman quickly assembled to reveal a photo of the founders of USC’s Jimmy Iovine and Andre Young Academy for Art, Technology, and the Business of Innovation (the latter founder is more commonly known as Dr. Dre), the words “Congratulations, Will,” and a welcome that touted Berman as “an essential piece” of the class of 2019.

In Berman’s mind he and USC fit together perfectly the minute he discovered the Iovine and Young Academy’s program online. “I walked the laptop over to my mom,” he recalls, “and told her, ‘This is the college I’m going to.’” Despite its traditional trappings-football games, marching band, Greek system-USC is a leader in interdisciplinary education, and the academy’s integrated focus matched Berman’s interests seamlessly. “Everything about it screamed ‘right up my alley,’ ” he says. “I had a bunch of different interests, and they would allow me to pursue all those areas at once.”

At New York City’s Riverdale Country School, Berman was an A student. “It’s not that he could have gone anywhere,” Katz says,“but he was a reasonable candidate for any school.” He applied to other top colleges and had already been admitted to one Ivy League school: Brown, where Katz and Berman’s father had both studied. “Part of me was like, ‘Are you sure?’” Katz recalls. She urged him to weigh his options and to consider her alma mater.

“He was having none of it. Once he got into USC, that was it.”

Berman has plenty of company. Through aggressive investment, recruitment, and marketing, USC has emerged as one of the nation’s most coveted undergraduate destinations and a top alternative to the Ivies, attracting elite students with the seemingly paradoxical pairings of a progressive curriculum and traditional charm, academic rigor and California chill.

The rapid rise in both popularity and prestige is all the more striking in light of the school’s historical place in the higher education firmament. For years USC has been the Elle Woods of universities, its academic excellence obscured by lingering stereotypes, just as with the protagonist of Legally Blonde (which was filmed on campus, USC standing in for Harvard). To people of a certain age USC will always conjure images of Barbiesque blondes in white Cabriolets and tanned jocks with popped polo collars. Exclusive but not elite, it was stigmatized with the sobriquet University of Spoiled Children.

Whether Southern Cal continues its rise, however, may be determined by how it addresses a spiraling scandal. In late May the university’s president, C.L. Max Nikias, agreed to step down following an outcry from students and faculty over incendiary reports that revealed that George Tyndall, a campus gynecologist, had remained in his position for more than 20 years despite repeated complaints of sexual misconduct. After an internal inquiry, the administration quietly terminated Tyndall in 2017 and gave him a payout (Tyndall has denied any wrongdoing), leading to accusations of a cover-up.

In a statement on behalf of the board of trustees, Rick J. Caruso said, “We have heard the message that something is broken and that urgent and profound actions are needed.” By then the Los Angeles Police Department had opened a criminal investigation, after more than 300 former patients came forward.

Before resigning, Nikias acknowledged that Tyndall “should have been removed and referred to the authorities years ago. I am struggling with the question-as you are: How could this behavior have gone on for so long?” His successor will be asked to perform a balancing act on arrival, answering that question while simultaneously limiting the damage to USC’s reputation.

Perceptions are notoriously slow to change, after all. No one is surprised to learn that USC has produced more Olympic athletes than any other university, the second-most members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and 77 Oscar winners. People’s reaction to learning that USC’s current faculty includes four Nobel laureates and four recent winners of the MacArthur genius grant is decidedly different. The school has become a magnet for world class academic talent.

One such addition is Amber Miller, who in 2016 decamped from Columbia University, where she had been dean of science, to be dean of the Dornsife College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences. Since taking the reins of the university’s largest and most diverse school, Miller has been struck by USC’s sudden popularity.

“What’s the secret sauce?” she asks. “I think there’s a unique combination of things: the individual attention to undergraduate education that you get at a liberal arts college; the big research mission, with exciting Nobel Prize winners and all the great programs. And combine that with school spirit: the marching band and all that excitement and energy. A place like Columbia, where I came from, has the first two things, but not the school spirit.”

“USC fits into this unique category,” says Kat Cohen, founder and CEO of Ivy Wise, a college counseling service based in New York City. “It’s medium-size, it has global appeal, and almost no matter what you want to study, it has excellent specialized programs.” In 2016, 8 percent of Ivy Wise students applied to USC; this year the number soared to 20 percent, on par with perennial favorite Brown.

While heat can be hard to quantify, USC’s numbers are eye-opening. Undergraduate applications for the fall of 2018 skyrocketed 14 percent, to 64,256, the most in USC’s 138-year history. A mere 8,258 students were admitted, which means the acceptance rate fell by 3 percent to a record low of under 13 percent-a drop made more notable by the fact that USC had already been getting top students.

“It has become one of the West Coast’s most selective private universities,” says Charles Loxton of Advantage Testing, a test prep and tutoring service that has offices across the U.S. and in the UK. “It has become a top choice for high-achieving students.” Which is to say USC has put the lie to its other unflattering nickname: University of Second Choice.

“We’re going head to head much more against long-standing academic powerhouses, whether that’s the Ivies or MIT or Stanford,” says Tim Brunold, dean of admissions. “This incredible increase in interest has not happened by chance. It’s something USC has been working on for decades.” Clearly, Southern Cal’s administration knows that image rehabilitation doesn’t happen overnight.

The seeds of USC’s ascent were sown during one of the darkest times in the university’s and its city’s recent history. After the 1992 L.A. riots, when the nearby South Central neighborhood burned and the military was deployed to restore order, USC’s president, Steven Sample, was urged to relocate the school-or, as he called it, “do a Pepperdine,” referring to the school that fled Watts for Malibu in the aftermath of the 1965 riots

Instead Sample decided to double down on Los Angeles. Faculty and students fanned out to volunteer in the area around the campus, and USC launched 300 community out-reach programs, which led to its being named Time’s College of the Year in 2000.

The decision to make Los Angeles part of the USC experience has paid off handsomely. Once an albatross, the school’s location south of Downtown is now an asset, attracting students drawn to a university in a city brimming with cultural cred. Meanwhile, students can hike up to the Hollywood sign or surf El Porto’s breaks early and still make their midmorning class.

The student body’s satisfaction shows. “If you’re going on what you feel when you visit campus, it has really good energy,” says one New York City parent who asked to speak anonymously so as not to affect her child's chance of admission. “The resources are just so impressive. You see that walking around.”

Behind those resources is the engine that has driven USC’s rise: fundraising, which picked up under Sample and took flight under Nikias. When the university launched a capital campaign in 2011 with the goal of raising $6 billion, it was seen as an audacious move, if not outright hubris. Nevertheless, thanks to the “Trojan Family,” as the alumni network is known, the school reached that amount 18 months ahead of schedule, raising as much in six and a half years as it had during the previous six and a half decades.

The endowment has funded 100 new faculty positions and a massive expansion in recent years. The Glorya Kaufman School of Dance was founded in 2012, and by the time its new building was completed, in 2016, it was already siphoning off students accepted at Juilliard. Last year saw the opening of a new $700 million student village, which has housing for 2,500 undergrads, a sun-baked quad presided over by a clocktower, and commercial spaces that house a Target, Trader Joe’s, and CorePower Yoga.

The interiors are modern, and some of the facilities, such as the fitness center, are state of the art. But the new dining hall resembles Harvard’s (or Hogwarts’s, as several students joked), and the village’s architecture is neo-Gothic collegiate. At the ribbon-cutting Nikias poked fun at his school’s striving. “The looks of the University Village,” he told the crowd, “give us 1,000 years of history we don’t have.”

The village also shines a light on the less savory side of the school’s past. Funded by an anonymous private donation, Cowlings Residential College is named for Al “A.C.” Cowlings, the USC football star best known for having driven the infamous White Bronco of fellow Trojan legend O.J. Simpson, in 1994. In 2010, USC was hit with a raft of NCAA sanctions, and the football team’s 2004 national championship was vacated.

Since last fall, members of the men’s basketball team and its coaching staff have been implicated in an ongoing FBI investigation into bribery and corruption. This followed the Carmen Puliafito scandal, in which the dean of the medical school was fired after videos of his drug abuse surfaced.

Reaction to these cases, however, pales in comparison to the current uproar around USC’s handling of the Tyndall allegations. A basic responsibility of any school is to ensure the safety of its students, and failing to do so can have consequences, says Ivy Wise’s Cohen. “Take Penn State: There was a 10 percent drop in undergraduate applications in the admissions cycle immediately following the Sandusky scandal.”

Penn State’s numbers have since rebounded, which Cohen says is not surprising. “It’s rare that we see a huge decline in a school’s popularity following a big scandal, and when there is, it’s often temporary. For better or worse, students may not feel there is an imminent threat [after a scandal], since many times these allegations happened decades ago, and the perpetrators have already been removed from their positions.”

Not only is Tyndall gone, Nikias is too, and his legacy (and the cost of USC’s recent rise) is being debated. “Nikias has become both the symbolic and actual target of justified criticisms and sometimes ill-founded anger,” wrote Leo Braudy, a USC English professor, in an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times. “But it does little good to vilify someone who has presided over so many positive changes at USC.”

In a separate Los Angeles Times op-ed, William G. Tierney, a professor and co-director of the Pullias Center for Higher Education, argued that the pace of change at the university may have been the core of the problem. “This is the tragedy at USC: Instead of cultivating an environment of reflection and reasoned debate, the university sprinted toward growth.”

The administration’s response to our queries reflects this divide, offering promises of self-examination amid reflexive self-promotion. “USC, now recognized as one of the nation’s preeminent universities, is diligently addressing its recent challenges,” Brunold says. “Our students’ well-being is our number one priority, as USC remains committed to providing an unparalleled education, complete with world class faculty, cutting-edge research opportunities, and an engaging campus environment.”

At risk of being obscured by the Tyndall affair are the efforts USC has made in pursuit of high-minded goals, most notably inclusiveness. This former enclave of Spoiled Children has been widely praised for its devotion to access. USC’s deep pockets ensure that every admitted student is able to attend.

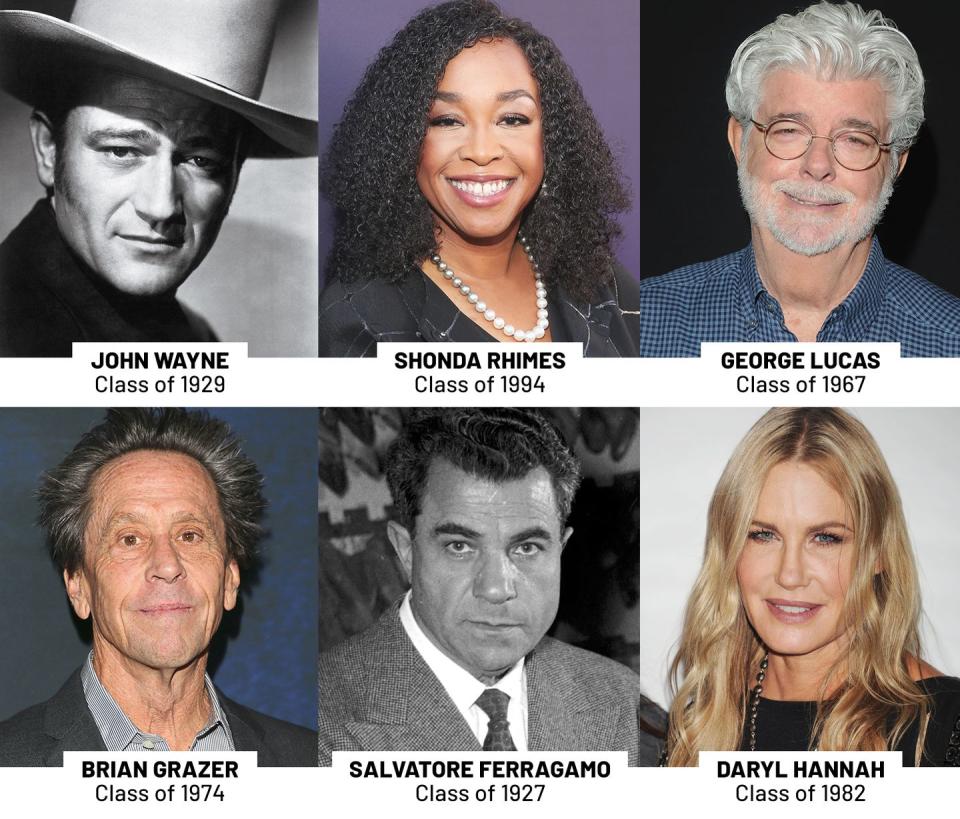

More than two-thirds of undergrads receive some form of financial aid, and approximately 55 percent are given grants or scholarships. Trojan alums have encouraged this initiative. George Lucas (class of 1967), who had already made the single largest donation in USC history in 2006 ($175 million to the film school), made $10 million gifts in both 2016 and 2017 to provide scholarships for African-American and Hispanic students, as well as for kids from other underrepresented groups.

Some investments aren’t donations as such, but they are making the school a cultural hub. Seeking a home for the futuristic $1.2 billion Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, the creator of Star Wars chose a site in Exposition Park, just across the street from USC.

Similarly, in 2006 Lucas’s friend Steven Spielberg moved the Shoah Foundation to USC. Renamed the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education, it has evolved into a center for research into both the Holocaust and broader genocide studies. Spielberg’s choice is noteworthy, since the famed director is not an alum-he wanted to go to USC’s film school but was rejected.

Neither Iovine nor Dr. Dre graduated from college at all, yet they handed the school $70 million in 2013 to fund their academy. Before selling Beats by Dre to Apple for $3.2 billion, the pair had been contemplating the future of their speaker and streaming music company. They asked,“Who is teaching at this critical intersection of culture and tech and business?” The response was: no one.

After an initial conversation, Nikias quickly convened a team from multiple schools to sketch out plans for the academy. Five years later the first graduates received their self-designed degrees. When asked about the impact of Nikias’s departure, Iovine expressed confidence in the academy’s future. “USC has shown enormous support for a unique idea, and Dre and I are thrilled with what has been accomplished in this short period,” he said, adding, “This is a difficult time for USC, and our thoughts are with everyone in the USC community.”

Spencer Wisch, a junior from New York City, summarizes his education at USC succinctly: “You’re going to actually do what you love.” He arrived on campus secure in the knowledge that that would be architecture, but his certainty began to erode as soon as it was time to choose his courses. “I thought, I’m going to this unbelievable school with all these great classes, and I felt I was being limited.”

After sampling a variety of subjects, Wisch is now a political science major with a minor in sports media. He lives near campus with seven other students.“My friends are business majors, computer science, engineering, premed,” he says. “We all come from different backgrounds, but we get to enjoy one another and learn about what we’re studying.”

Wisch, who grew up on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and attended Trinity School, doesn’t consider himself a rah-rah kind of guy. He remembers when USC’s school spirit won him over, after a late night study binge at Leavey Library. “I’m leaving at 4 a.m.,”he recalls, “and I see all these people standing around Tommy Trojan. I’m like, ‘What are you guys doing?’ and they’re like, ‘We’re guarding him.’”

The group, known as the Trojan Knights, keeps watch over the statue around the clock during rivalry week, the walk-up to the annual football showdown with UCLA. The Knights had wrapped the bronze warrior in duct tape from helmet to sandals to protect him from the slings and arrows and paint balloons of pranksters from across town. “I didn’t think it was weird,” Wisch recalls. “I was like, ‘That’s awesome!’ ”

Wisch had his parents’ full support when he decided to apply to USC. However, others at Trinity were less enthusiastic. “I remember one kid talking about it right in front of me: ‘Oh my god, he picked USC over Virginia? What was he thinking?’ Even one teacher was like, ‘Interesting...,’ which annoyed me. A lot.”

The lag between USC’s ascendance and the acknowledgement of it, especially on the East Coast, can be attributed to old stigmas and snobberies, but also to the speed of the school’s transformation. “For whatever reason, it seems that change and reinvention can happen faster on the West Coast,” says Spencer’s mother Debi Wisch, a producer of films about the arts. “Five years ago L.A. was an up-and-coming art destination. Now it’s one of the most important places in the art world. It’s a little like that with USC. People used to ask, ‘Why did Spencer apply?’ Now it’s, ‘How did he get in?’ ”

Some people consider USC’s recognition overdue, another L.A. product, like cold-pressed juice or Korean tacos, for which widespread appreciation was only a matter of time. “Once I came out here, it was funny to see how prestigious USC felt to people who had grown up in Southern California,” says Will Berman.

He’s speaking about the school’s skyrocketing reputation, though USC’s newfound notoriety can cut both ways-and the same is true of the increasing national awareness of the Tyndall scandal. “It’s cool to see that bleeding over to the East Coast now,” Berman adds. “It’s about time they caught up.”

This story appears in the August 2018 issue of Town & Country.

Subscribe Now

You Might Also Like