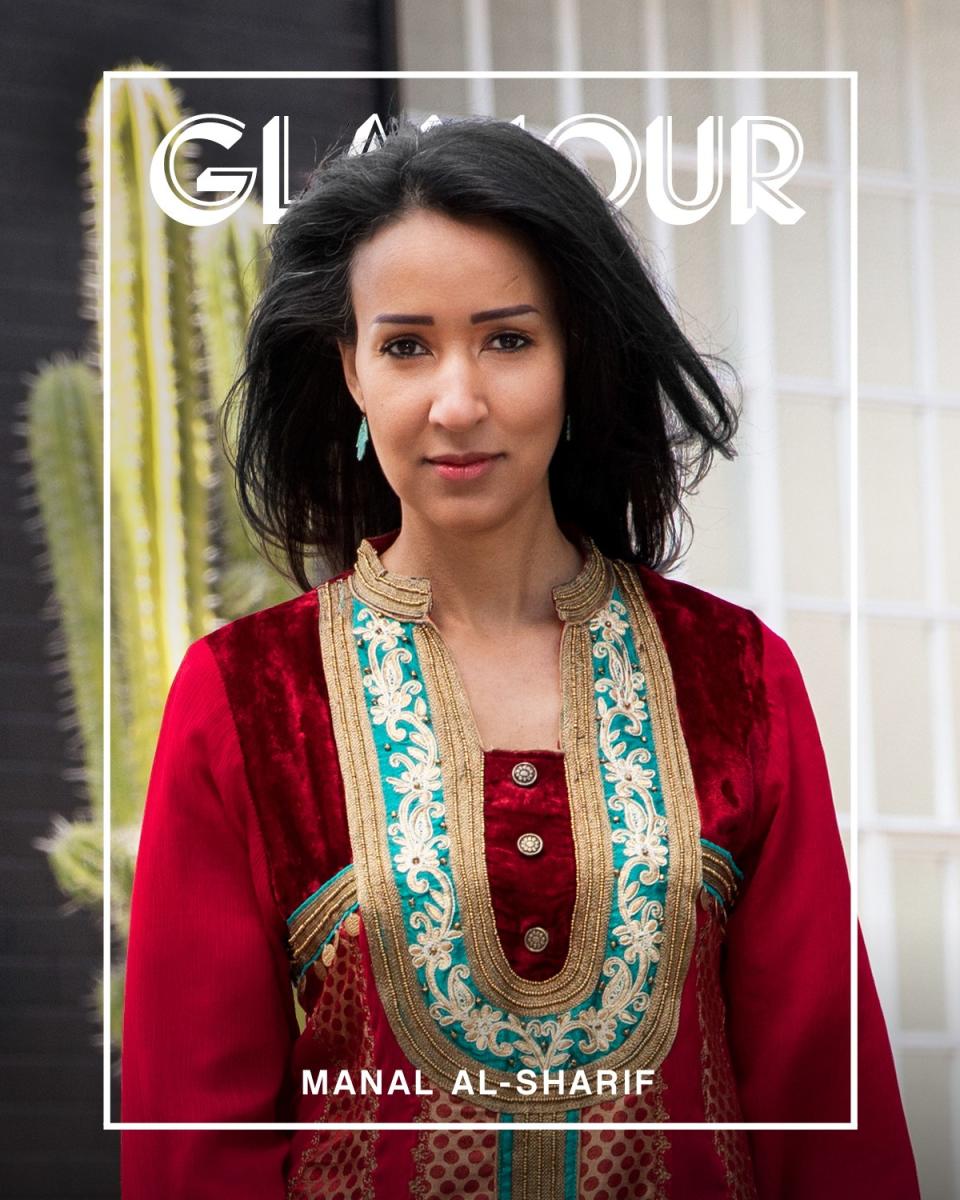

Saudi Arabia Was the Last Place in the World to Allow Women to Drive. Manal al-Sharif Helped Change That.

It was the painting of two Saudi women weavers on the wall in my apartment that Manal al-Sharif noticed first. During our FaceTime call, the breathtaking view of Sydney’s Parramatta River playing peekaboo in the background, she shared her own still-life drawings—two sets of meticulously sketched eyes and a realistic still-life of pumpkins. This is the only art that remains after she burned select pieces some years ago, believing images of humans and animals to be unholy in her birthplace of Saudi Arabia.

“I am back to art, finally,” she tells me later. It’s a remarkable liberty she now enjoys in her home in Australia, where she can race off in her Nissan on a moment’s notice. These are things al-Sharif, 39, does not take for granted. Thanks to her efforts, and those of her fellow activists, Saudi Arabia is no longer the last country on earth where women aren’t allowed to drive; on June 24, the nation declared women could get behind the wheel without a male guardian. But it’s a bittersweet victory for al-Sharif: She remains in self-imposed exile, one of many Saudi women activists to leave the country after the ban was lifted for fear of imprisonment. Out of nine of her compatriots, several are still behind bars. Nevertheless, her resolve to push against the status quo remains.

Al-Sharif grew up in Mecca with Muslim parents. She tells me she was always curious as a girl. “When they told me I can’t do this, I can’t read that, I would ask, ‘Why?’” she says. “I was always questioning: Why are there no women leaders? We were invisible in my society, and that bothered me so much. They say to us: ‘A woman leaves her house twice—once to her husband’s house, and the second to her grave.’ That is just so sad. I wanted to be me.”

In 2011 the computer scientist was a divorced single mother with her own house and money. “I made decisions in my life,” she says. She had her own car too, but couldn’t drive it without a male guardian. When she complained to a coworker about the unjustness, he told her there was no formal law against driving—women just couldn’t get a driver’s license. That’s when al-Sharif helped launch the Women2Drive campaign. Several activists got behind the wheel, but to galvanize support, al-Sharif videotaped her drive and posted it on YouTube. The clip went viral.

The authorities, unsurprisingly, did not rally behind al-Sharif the way women did; she was detained twice and imprisoned for nine days. Even when she was released, she was sequestered in her own country. “I was threatened, cornered, harassed,” she says. Her brother had to flee the country with his family. But most painful? The day her son Abdalla came to her bruised from a beating at school. “One of the kids had asked, ‘What do you think of Manal al-Sharif?’ and the teacher said, ‘She is crazy and should be under arrest,’” she recalls. “And he said, ‘Mom, jail is for bad people.’” After that she began shielding her son from her work, but didn’t give up.

“I was always questioning: Why are there no women leaders? We were invisible in my society, and that bothered me so much.”

Her activism cost her her job. When she tried to remarry, the government refused to grant her permission. She and her Brazilian husband wed anyway—which cost her custody of Abdalla. He must remain in Saudi Arabia with his father; he cannot visit her in Australia or meet his new brother, Daniel. Similarly, she cannot visit him without risking imprisonment. She feels tremendous sorrow that they are apart; for now she’s compiling every news clipping about her work and awards alongside a copy of her memoir, Daring to Drive, in a box for Abdalla. She hopes that one day she can tell him her own narrative, a different one from that of those who maligned her for challenging tradition and patriarchy. “Eventually,” she says, “he will know.”

Then there’s the frustration that her compatriots are not free. “Loujain Hathloul, Eman al-Nafjan, Aziz al-Yousef,” she says. “Samar Badawi and Nassima al-Sadah—I met every single one of these women…. I broke bread with them. We have been together from day one.” So she continues to fight for autonomy from existing guardianship laws. “I’m not free until we all are free,” she says.

She has to go now, to drive to pick up Daniel—an everyday act of freedom for mothers around the world. I have to know: Who inspires her? “Saudi women,” she says without pause. A woman there, she continues, “is stripped away from all her rights, her face, name, and identity. And yet she is there. She is a survivor; she’s a fighter. She makes it against all the odds.”

Jamia Wilson grew up as an American expat in Saudi Arabia and is executive director and publisher of the Feminist Press.