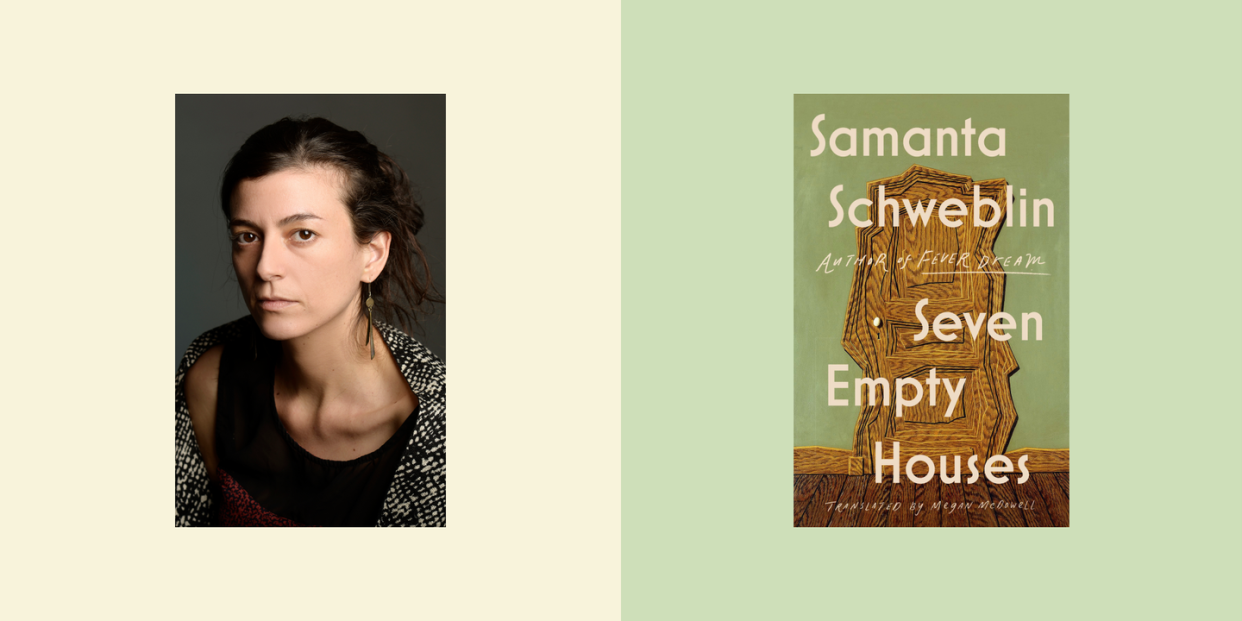

Samanta Schweblin Infuses Dreamlike Menace into “Seven Empty Houses”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When is a pipe not a pipe? In 1929, the Belgian master René Magritte painted The Treachery of Images, a surrealist touchstone, iconic whimsy with the caption Ceci n’est pas une pipe (“This is not a pipe”). Enthralled by the rise of psychoanalysis and the illogic of dreams, he depicted recognizable objects and figures stripped of context—a train emerging from a fireplace, bowler-hatted men suspended in air—wispy brushstrokes evoking the nightmares of modernity.

And when is an empty house not an empty house? That sense of dreamlike menace infuses the linked fictions in Samanta Schweblin’s Seven Empty Houses, beautifully translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell. Schweblin’s houses are not, in fact, empty: They’re occupied by characters who live a frequency away on the cosmic dial, accessible as Magritte’s images but just as strange and strained, boxed in psychic spaces that out-Freuds Freud. These stories pulse with blood and lust, ego and id, as Schweblin punches above her weight.

She pumps up the creepiness, even among mundane details. In “Two Square Feet,” the narrator wanders a noirish Buenos Aires, seeking aspirin for her mother-in-law, knocking on the doors of shuttered pharmacies and shunning subway tunnels. But the warmth of indoors is equally frightening; Schweblin teases out the tensions just so. “My mother-in-law put up a Christmas tree over the fireplace. It’s a gas fireplace with artificial rocks, and she insists on bringing it along every time she moves to a new apartment. The Christmas tree is pint-sized, skinny, and a light, artificial green. It has round red ornaments, two gold garlands, and six Santa Claus figures dangling from the branches like a club of hanged men . . . the Santa Clauses’ eyes are not painted exactly over the ocular depressions where they should be.”

Those uncanny details ripple outward. Windows—picture windows in particular—underscore the theme of voyeurism. Schweblin’s characters are intruders, violating each other’s domiciles. “None of That” recounts one woman’s indulgence of her mother’s asocial behavior, stealing into mansions and wreaking havoc as residents watch, mortified. In “Out,” a woman, just emerging from the shower, breaks off a tense conversation with her husband, putting on a robe and toweling her hair as she darts into the night, embarking on an eerie adventure reminiscent of David Lynch’s “Lost Highway.” The narrator of “My Parents and My Children,” caught in an emotional crossfire between his ex-wife and his dementia-afflicted parents, vows to shield his son and daughter from the adult world. And in “An Unlucky Man,” an 8-year-old girl discovers her own agency when pitted against a predator.

In the collection’s strongest piece, “Breath from the Depths,” Lola, an elderly woman in the throes of a final illness, confines herself to home, stalked by shadows and a possible romance between her husband and an adolescent boy next door. She writes down shopping lists, lists for how to handle her spouse (who appalls her), lists that morph into road signs that steer her inexorably toward terror. She realizes something’s wrong but can’t put a finger on the problem. She searches for a box of cocoa hidden among her shelves: It’s missing, or it’s there, or it’s there but only half-full.

Schweblin tells all the story but tells it slant. Lola hears noises, from sinister neighbors and gangs that roam her street, unseen teenagers who ping her bathroom with pebbles. She studies her husband as he waits on her: “She looked at his hands—so unmasculine now, white and fine with carefully filed nails—and the little hair left on his head. She didn’t reach any great conclusion or make any decision in that regard. She just looked at him and reminded herself of concrete facts that she never analyzed: Fifty-seven years now, I’ve been married to this man. This is my life now.” Lola’s revelation comes as a shock.

Schweblin is at the forefront of emerging Latin American writers, defiant and assured, swaggering among the jungles of sex, love, and politics. Like her fellow Argentine Mariana Enriquez, she tinkers with the envelope of narrative: She’s a tad more restrained, though, focused on the liminal spaces between what we know and what we desire. As in her previous acclaimed works—Fever Dream, Little Eyes, and A Mouthful of Birds—these stories probe the horrors and betrayals in our most intimate relationships, from mothers and daughters to married couples. We’re all empty houses, Schweblin suggests; no amount of decorative furniture and small talk can fill us. Magritte’s surreal interiors hinted at the macabre; nearly a century later, Schweblin brings his disquieting vision full circle.

You Might Also Like