Sally Kohn Says Everyone Can Unlearn Hate

In April of 2016, Sally Kohn publicly endorsed Bernie Sanders at a rally in Washington Square Park. As she spoke, her then 7-year-old daughter, Willa, a Hillary Clinton supporter, stood by her side. When Kohn mentioned that Willa is a Hillary fan, Bernie supporters in the crowd booed. Backstage, Kohn remembers her daughter asking, “Were they booing me?” Kohn came up with a white lie, telling Willa the crowd wasn’t booing, and that cheers can sometimes sound like boos.

But Kohn, who was the “lefty lesbian” (her term) on Fox News until 2013, and is now a commentator for CNN, knew better. She had experienced the vitriol of partisan politics as a talking head at a conservative network, and she’d seen the heightened emotions sparked by the 2016 presidential election. In her new book, The Opposite of Hate: A Field Guide to Repairing Our Humanity, Kohn addresses the role that hate plays in our lives and how anyone—even a former neo-Nazi-turned-Buddhist—can change.

Her book, out Tuesday, is already getting some high-profile praise. On Monday, she shared a photo of Sir Ian McKellen and Sir Patrick Stewart reading a copy. On her Instagram story, she posted photos of everyone from Sophia Bush to a group of alpaca enjoying their books. Kohn spoke with Vanity Fair about the debut as an author, and why people are getting so excited to read something called The Opposite of Hate in the Trump era.

Vanity Fair: In the introduction of your book, you write about a memory of bullying another girl in the fifth grade. As an adult writing this book, what was it like to process that memory and your feelings of hate or anger as a young girl?

Sally Kohn: Honestly, it’s more about shame and regret. I think at the start I had this sort of fear that if you can do something that bad, you must be a bad person. One of the selfish comforts I took from learning more about the history and psychology, in neural science and hate, is actually that we all have this capacity to do mean things, from small to grand. And, in a sense, it made me at least realize the fact that, “Look guys, I’m not necessarily intrinsically mean.” But it also kinda says, “O.K., well now, pressure’s on. You got to make active choices. How are you going to make sure you keep making different choices?”

When did you realize that not everyone who says and does hateful things is a bad person?

You know, I thought walking in the door of Fox News as a lefty lesbian was going to be a story about them and their hate. I really did. It was like, “Oh, O.K., they’re hateful.” Oh, poor little old me, walking into this den of hate. So it was the realization of, “Oh, hey, wait a second, some of these people are like nice, normal people.” Some of them are super kind, and surprisingly so, and more complicated and nuanced in their views.

What is the main thing you took away from your research about how we process and feel hate over the course of our lives?

We have hardware that predisposes us to, when we group people into us-versus-them, kind of the primal, evolved hardware. However, the software is what’s included in terms of who we learn to hate, how we decide to decide who is “us,” and who is “them.” That is not written into the neurons of our amygdala. There’s not a gene for racism. That is what we have all learned and habituated and been taught, because of our history, our society, our culture, our laws, our institutions—we learn to hate.

How does information about “software” apply to America’s children, especially in this political time?

I think about kids, small kids, like elementary school kids, who go to, for instance, racially integrated schools. Studies suggest they don’t develop racial bias or as much racial bias in the first place. And, by the way, that there are things you can do to reverse it. So, when kids who are older—high school or college—participate in racially integrated activities and after-school programs, then their bias reduces. The software is malleable. The software can be coded and decoded. History can change, we can change.

Since writing this book, what have you learned about how we can all better get along with those who might not agree with us?

We need to have more and more people who support justice, equality, fairness, and the policies, practices, and habits that get us closer to it. So, just forget the moral, and look at the pragmatic level, I don't see how demonizing people who disagree with you gets you closer. And morally, you are not walking the talk. You’re saying as a progressive, “Listen, I think we should treat everyone with equality and fairness and dignity except Trump supporters.” If I have a big asterisk for Trump supporters, am I really standing up for the dignity and humanity of all?

I’m sure you saw Christine Quinn’s comments a couple of weeks ago about Cynthia Nixon, calling her an “unqualified lesbian.” When you get the kind of hate that cuts to the core of your identity, where does that go for you? How do you process that?

The writer Ann Friedman has this disapproval matrix, and I think about that a lot. She writes about the distinction between haters and critics. I think about that constantly, because you look at people coming in on social media, and they’re being strangers. But still, are they critics or are they haters? And sometimes it’s hard to know. And what’s very interesting about it is sometimes my gut reaction to something someone says or tweets at me is based on how I categorize them.

If I perceive that they’re a progressive, they’re not. That’s my own hypocrisy. That’s my own bias. As opposed to actually saying, like, “Oh, O.K., they’re conservative, but do they have a point? Are they raising this to make a substantive point? Or are they just being a hater?”

I never took it personally, for the most part. When some people call me stupid, I’m like, “Eh, I know I’m not stupid.” Now, if they say I look fat on television? No woman likes being told they look fat on television, and men don’t either. But if they say, like, I’m a man-hating lesbian, I happen to know I’m not. So, I’m good. I’m at peace with that.

Speaking of your haters, you write about confronting one of them on the phone. What was the experience of talking to these people like? What insights did you gain about them?

My big takeaways from talking to him and a bunch of my trolls, including my most vicious trolls, is so many of them didn’t feel seen or heard. I mean, here I was actually thinking that they’re hurting me and they’re feeling, “Well, how could I even hurt you, no one even reads my tweets. No one cares about my opinion. No one pays attention to me at all.”

And, the second thing was, a lot of my trolls had expressed a sentiment of, “Look, I felt justified.” The way they would frame it is, “I wasn’t being hateful, you’re hateful.” I’ve talked to friends who I know to be good, loving, well-intentioned, decent people—but online, when someone is mean to them, gloves come off. Someone else’s hate justifies your own, or actualizes your own. And then that is the sort of psychological appearance of the notion that hate begets hate.

Speaking of hate, was there a particular point in the election where you just sort of snapped and went, “I have to write this book?” Was there a debate, or a moment, or was it a build up?

I actually started coming up with the idea for the book during the 2016 election while I was going on air at CNN and going around the country and giving speeches. I was watching what was happening and saw our country in crisis. I mean, there were lots of moments during the actual election where one could say I lost it. You know, so hopefully I regained some of my composure.

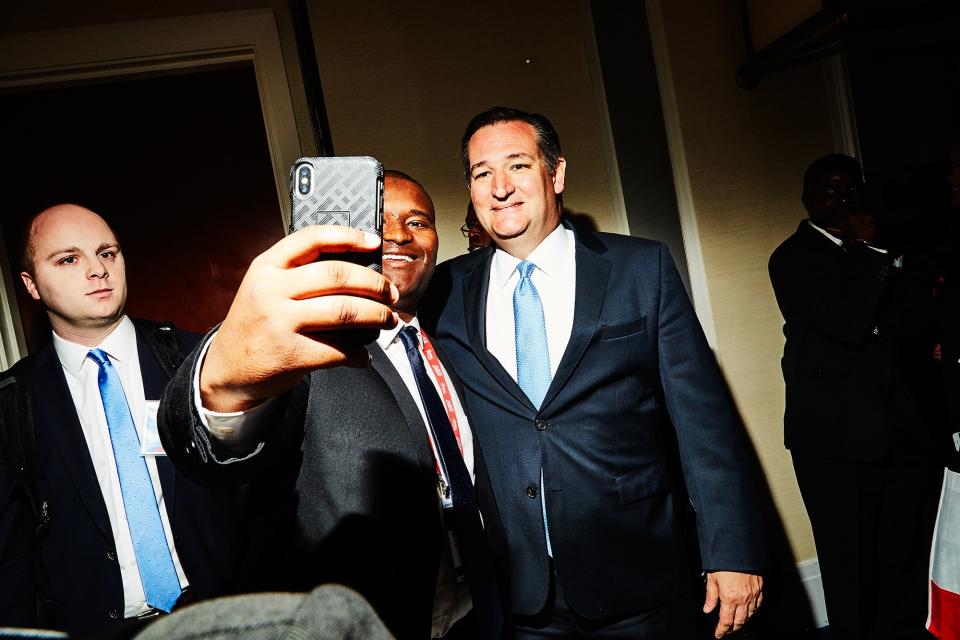

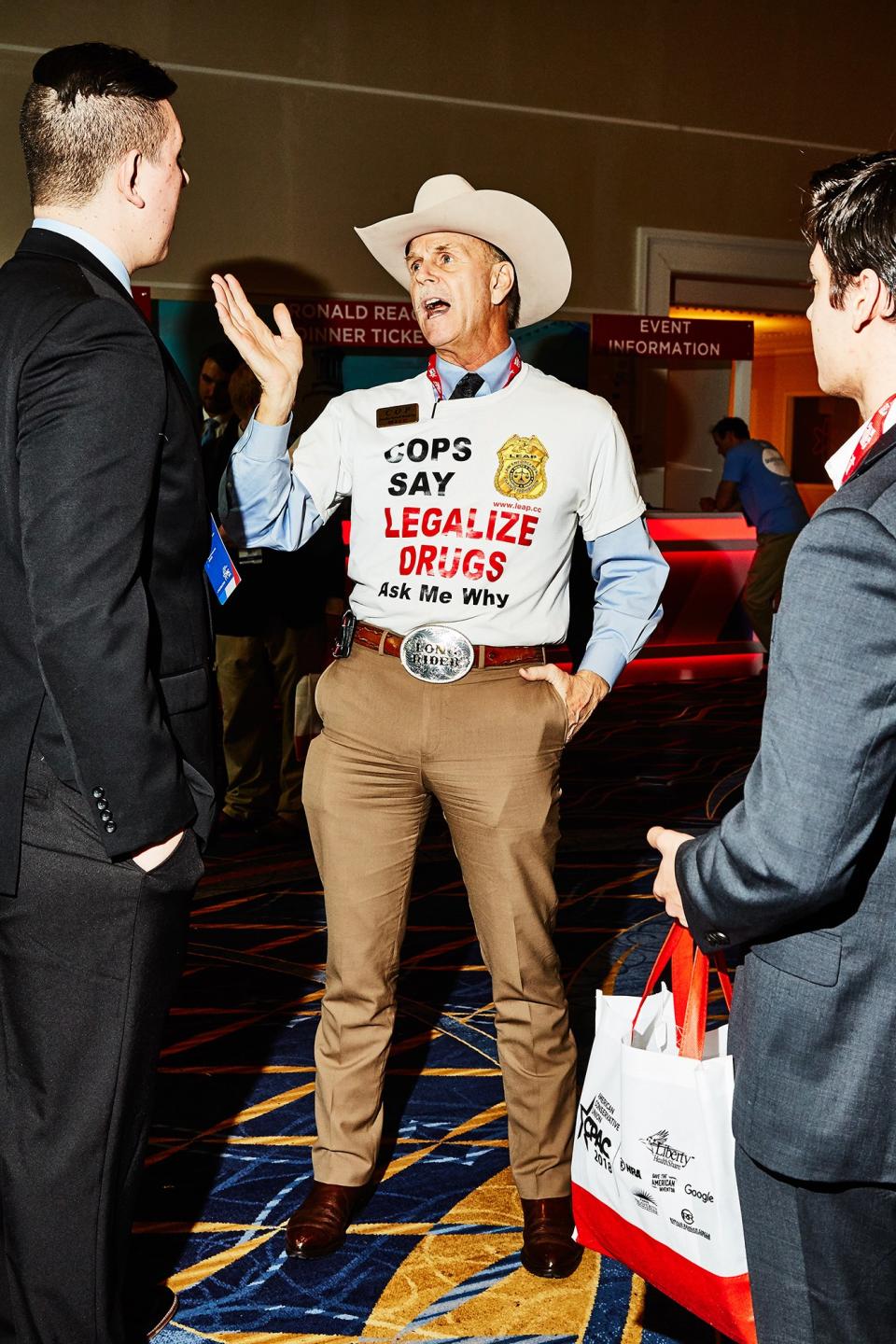

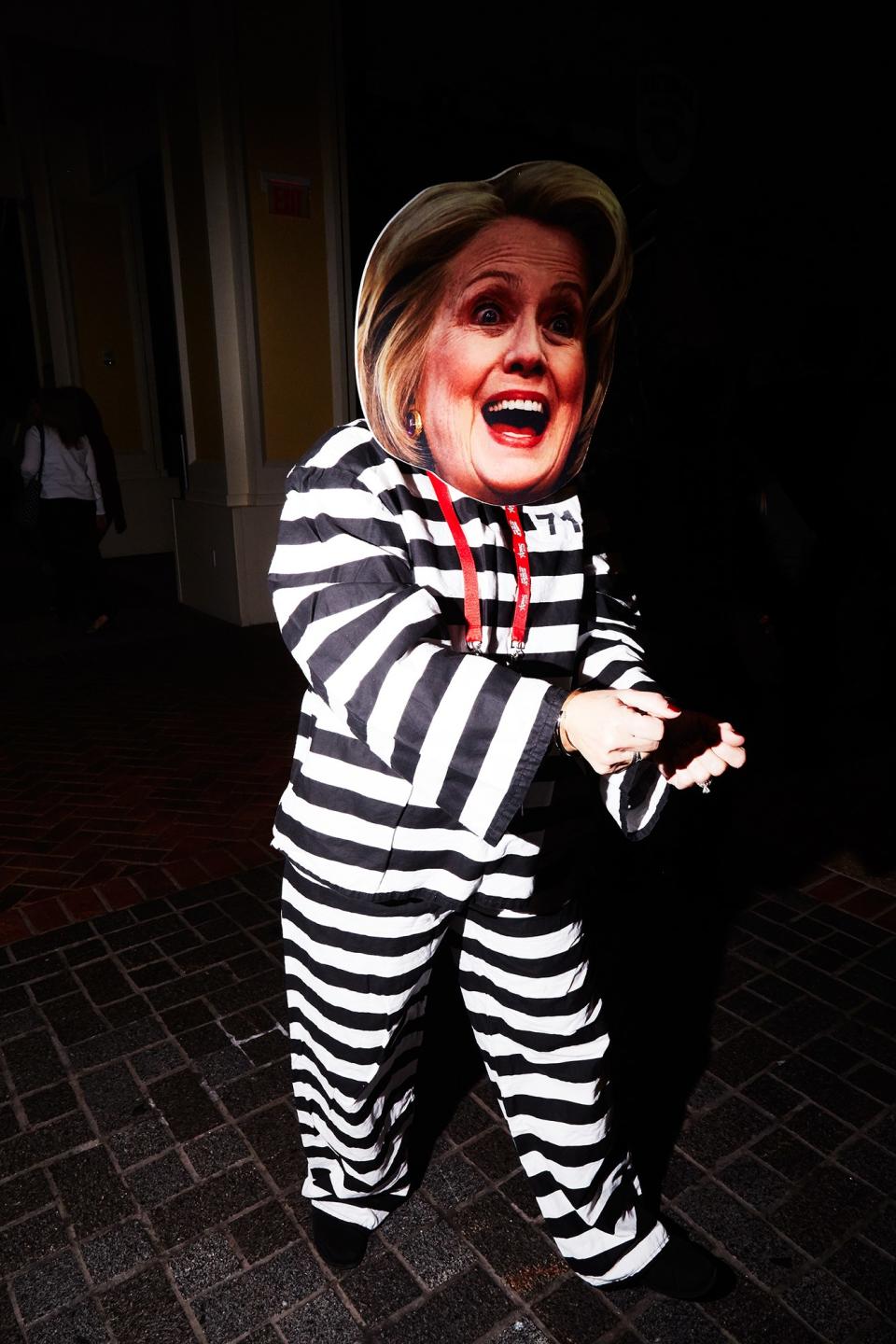

“The Greatest Carny Show on Earth”: Inside CPAC, the Super Bowl for Trump Supporters