Art market in 2018: a year when sales went up, records fell, but alarm bells rang

As the main salerooms wind down for Christmas, it’s a good moment to look at the directions in which the market has headed in 2018 – and where it might go next.

It’s been a good year for female artists. In the Old Master field, where there simply aren’t that many of them, the National Gallery paid a record £3.5 million in July for a self-portrait by Artemisia Gentileschi.

And this month, an American collector paid a record £1.8 million for a painting by the 17th-century Dutch artist Judith Leyster. This week, there has been an unsubstantiated suggestion that the Gentileschi could have been looted by the Nazis, but the Gallery found no evidence to support that.

At New York’s contemporary art sales in May, 15 records were set for female artists, headed by a Sixties abstract painting by Joan Mitchell, which sold for $16.6 million (£13.2 million).

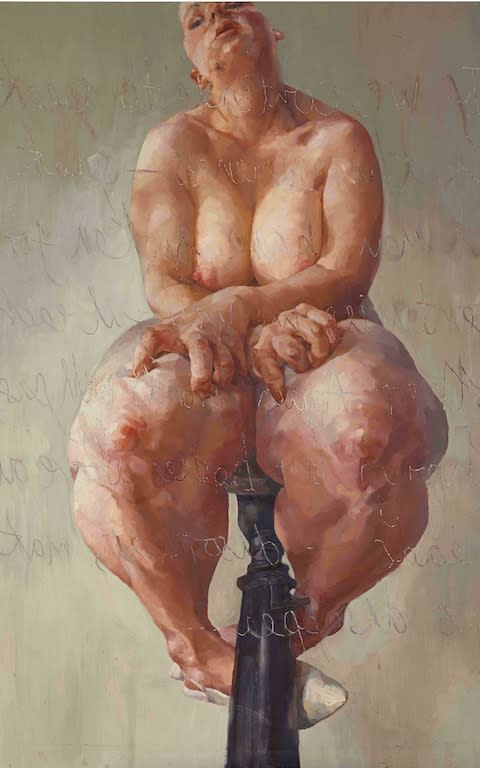

Leading the field for Britain were paintings by Cecily Brown at $6.8 million and Jenny Saville’s self-portrait, Propped, which sold in October in London for £9.5 million, making her the most expensive living female artist.

A month later, the sale of David Hockney’s 1972 painting, Portrait of an Artist, sold for $90.3 million, making him the most expensive living artist – surely a sign that British art is in the ascendancy.

The female wave was visible in the galleries, too. At Art Basel this summer, dealers were achieving prices in excess of auction records for artists such as Carol Bove, Cathy Wilkes, Huma Bhabha and Sheila Hicks.

Look closely, though, and you will notice that many of the artists experiencing rapid price increases are quite elderly (Rose Wylie and Carmen Herrera, for instance) or recently deceased. It’s part of the market’s continued search for neglected figures whose work can be bought cheaply and upgraded.

Contemporary art provided many of the year’s high spots. Perhaps the most vibrant sector was the African-American art market, which reached a crescendo in May when Kerry James Marshall’s Past Times sold to rapper Sean “P Diddy” Combs, for $21 million. A ripple effect was then felt in the November sales when a dozen records tumbled for African-American artists.

Another sector worth mentioning this year is graffiti or street-based urban art, which has infiltrated the mainstream contemporary art sales becoming, ironically, mainstream. Banksy’s shredded Girl with Balloon, which sold for £1 million, is the most notorious example.

But we also saw American street-artist-turned-toy-maker KAWS, who has hit Asia in a big way, exceed his dollar auction record, rising from $450,000 to $2.7 million.

New technology has also entered the mainstream. Last month, Christie’s broke new ground when it recorded its sale of the $323 million Barney Ebsworth collection of American art on a blockchain, and introduced the first work of art made by artificial intelligence.

The latter, a composite portrait that drew derision from conventional art critics, was estimated at $7,000 and sold for a highly speculative $432,500. AI has also been employed by Sotheby’s, which hired start-up firm Thread Genius to predict clients’ future purchases. But commerce cannot rely entirely on the technological revolution – growth in internet sales has slowed down, according to a Hiscox report.

Sotheby’s consolidated figures are not out yet, but we know from its website that auction sales rose to $5.2 billion this year, a 13 per cent improvement on last. Some of the smaller salerooms have done better. Woolley & Wallis in Salisbury, for instance, will report a 26 per cent increase during the year, with a turnover of £24.8 million.

This includes the only £1 million-plus sale in a British auction room outside London, thanks to a painting from the estate of Body Shop founder Anita Roddick by Chinese artist Yang Feiyun, which sold for £1.7 million last month.

In market share, Sotheby’s is slightly behind Christie’s’ $6.6 billion of sales (a sum that should be exceeded this year). And while Sotheby’s has already claimed victory over Christie’s in Hong Kong, it is unlikely to have competed in the crucial US market, where Christie’s conducted the sales of the Rockefeller and Ebsworth collection sales, which netted $1.1 billion between them.

Sotheby’s regional breakdown reveals a familiar distribution. Nearly $1 billion came from Hong Kong, narrowly exceeded by London ($1.3 billion), leaving Continental Europe on just over half a billion dollars, but with all three trailing North America ($2.3 billion). The American market seems to be thriving under the Trump regime; the French are anticipating a greater market share at the expense of Britain after Brexit.

In Asia, meanwhile, Sotheby’s proved successful at selling modern and contemporary Western art to the East, in its evening sales in Hong Kong; and Christie’s reported that 36 per cent of Asian purchases were of non-Asian art.

Looking at the dominant sectors of impressionist, modern and contemporary art, sale totals for the main seasonal series at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips have picked up, since a dip in 2016, and at $6.4 billion were on a par with the peak years of 2014 and 2015. According to some, that sales level has only been maintained by the use of $3.5 billion of pre-sale guarantee money, used to persuade owners to send high-end art to auction.

The risks involved in that strategy came under scrutiny when a large Modigliani nude that was under guarantee, and that made the highest price of the year at $157.2 million (including commission), turned out to be hardly profitable for Sotheby’s because the bid price ($139 million) was less than the amount the painting had been guaranteed for. Sotheby’s had to use most of its additional commission charge to balance the payment.

So, while sale totals have gone up, records been broken, the neglected recognised, and new technology embraced, there are warning signs that the ecosystem of the art market is adjusting.

Business was slower than usual this month at America’s top fair for modern and contemporary art, Art Basel Miami Beach. MCH, the Swiss company that owns the Art Basel fairs (in Basel, Miami and Hong Kong), witnessed some fragility after it took shares in fairs in Düsseldorf, Mumbai, London (Masterpiece) and Singapore but, reporting a fall in profits, pulled out of all but Masterpiece this summer.

This time last year, everyone was talking about the Leonardo da Vinci that sold to the Louvre Abu Dhabi for $450 million. But from being the sensation of the year, it has become the enigma. Amid concerns for its authenticity, it has not been seen since. In all corners of the art market, then, uncertainty is lurking.

Sign up for the Telegraph Luxury newsletter for your weekly dose of exquisite taste and expert opinion.