The safe-cracking heroin addict who exposed the hollowness of the hippy dream

“If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear a flower in your hair.” That’s how the 1967 Summer of Love has come down to us – a spontaneous blossoming of peaceful coexistence, a road-test for a whole new way of living. Sure, plenty of drugs and naked dancing and not a lot of washing. But it was also a last optimistic hurrah before the wave of assassinations and race riots burned through Vietnam-era America.

Or was it? Ringolevio, an insider’s memoir from 1972, long forgotten but now republished, reveals that the so-called Summer of Love was anything but summery and loving. Hard, uncomfortable fact: it was a largely commercial enterprise, the finely orchestrated brainchild of HIP, the Haight Independent Proprietors, the men (even in the equality boastful Sixties, it was still always men) who owned the shops lining Haight and Ashbury Streets, the city’s epicentre for those in search of The Hippy Dream.

A hundred years previously, the only people to make good money out of the Gold Rush were the shovel and rope sellers, supplying the needs of the soon-penniless prospectors. Now, again, HIP knew it had hit pay dirt. The previous January they had successfully hosted the Human Be-In. Billed as “a gathering of the tribes”, it wasn’t much more than a one-stage festival with poetry and speechifying. Jerry Rubin, later one of the Chicago Seven, called for a marriage of the Haight-Ashbury tribe and the Berkeley tribe. More pithily, Timothy Leary told them to “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

The Summer of Love – publicised nationwide – would take this to a new level, attracting countless new shoppers to the Haight. HIP, keen to have everyone onside, summoned a Council For The Summer Of Love in a Methodist church basement. But one local group, The Diggers, had already seen through this cynical commerciality. Naming themselves in honour of the 17th century protesters on St George’s Hill in Surrey who’d merely pleaded for land to cultivate, these new Diggers similarly put practicality before manifestos or idealism.

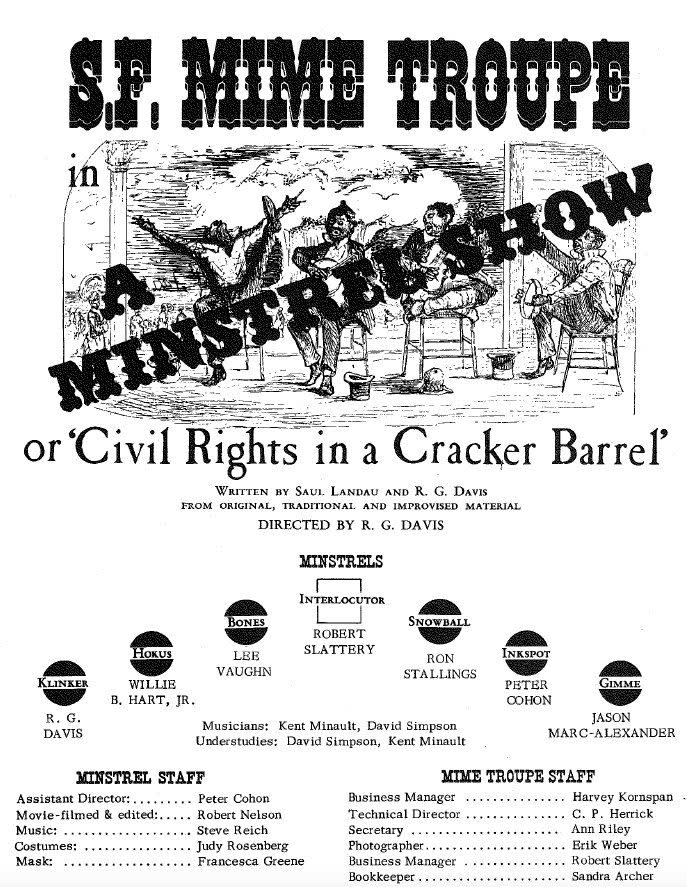

A collision between street theatre and plain old-fashioned anger, much of the group’s theatricality came from two Peters: Peter Berg, known as The Hun, and Peter Cohon, whose acting name became Peter Coyote. Both were mainstays of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, staging everything from Commedia dell’Arte to a blackface Minstrel Show using satire to advocate for Civil Rights.

But one day someone new asked to audition. Coyote, one of the last surviving Diggers and now a Buddhist priest after a successful career in Hollywood, remembers: “A lithe freckled man with flinty Irish features walked in...he had a chiseled face thrust aggressively forward, as if it were impatient with the body behind it.” This was Eugene Grogan, now going by the name of Emmett. And in the hands of Grogan, a charismatic but probably unremarkable actor, the Mime Troupe quickly switched from Pantalone to Street Protest.

But where had this Emmett Grogan sprung from? If the first half of Ringolevio is to be believed (and it does demand more than a pinch of salt), he had just been discharged from the US Army for wielding a bazooka while under the influence of dextroamphetamines. Prior to that, he had bummed round Europe – helping build a chapel in the Italian Tyrol, attending Film School in Rome, blowing up Armagh border posts with IRA buddies and writing pornography in London. All of this before his 25th birthday.

And anyway what was this Brooklyn boy doing in Europe? Try this: having got hooked on heroin as a teenager, he did six months on remand before winning a scholarship to a private school on the Upper West Side. There he scoped out his friends’ Park Avenue apartments, waited for their Christmas vacations, snuck back in (one time via the dumbwaiter), cracked the safes, and snuck back out again. Hence the speedy escape to Europe.

Like I said, if Ringolevio (a variation of the children’s game tag, which originated in New York) is to be believed. A later friend was a convicted cat burglar so he may well be the inspiration for that sequence. But, as I researched, other chapters, some even less believable, suddenly emerged as true. Did he really win a place at Europe’s oldest Film School at Cinecittà? Yes, I found his name on the 1965 admission roll. Was he ever in London? Yes, there’s his National Insurance Card, home address off the King’s Road.

So although Ringolevio may read as a barely credible bumper-car ride through a hard-scrabble childhood and a dissolute early adulthood, it does plausibly explain the Emmett Grogan who founded and led the Diggers on its counter-counter-culture crusade. It seems that Grogan was always going to do what he thought was right and count the cost later (and in 1975 he was found dead from a heroin overdose on the Coney Island Subway).

But back in the Haight-Ashbury of 1967, the Diggers were appalled by the sight of the hippy runaways, hungry and sick on the streets of “Hashbury”. So did they protest? Did they advocate? No, they established free food kitchens. OK, there was a small price: before eating, the kids had to step through a giant golden picture frame – known as the Free Frame of Reference – to inspire them to henceforth see the world differently (metaphors were important to the Diggers).

And in truth, the food wasn’t “free” either. As Grogan never tired of saying: “It’s not free because it’s yours.” This was the key to the Digger Philosophy: Everything Free. Even Coyote, who’d been away on tour when it was first instigated, remembers the full lash of Grogan’s righteous fury: “Emmett asked me if I’d like something to eat, and I said ‘No, I’ll leave it for people who need it.’ He looked at me sharply and said, ‘That's not the point’ and prised open a door in my mind. Feeding people was not an act of charity but an act of responsibility to a personal vision.”

From there, the Diggers graduated to a “Free Store” where everything remained free and if you asked for the Manager, you were told: “It’s you.” There were “crash pads” too, where doctors would come round and check on the kids – Frisco is a damp city, harsh on drug-smoking lungs.

As a group who combined activism with theatricality, the Diggers are surely the ancestors of everything from Pussy Riot to Extinction Rebellion. But it was also hard work: there was only so long they could get up and beg food each morning at the Produce Terminal, cook up the twenty-gallon cans of stew and deliver it all to Panhandle Park. Meanwhile, HIP was cruising on, using its Summer of Love to lure ceaseless waves of teenagers: they came for peace and love but ended up working in HIP sweatshops for two bucks an hour.

An early Digger piece of Guerrilla Theatre (it was Berg who coined that term) was a funeral procession marking “The Death of Money”. Less than two years later, they staged “The Death of Hippie” to mourn the commercialisation of the Haight. Most of the Diggers retreated to environmental activism in the California Hills, but Grogan went on to write lyrics with The Band, write Ringolevio, and hang out with Bob Dylan (who dedicated Street Legal to him).

1967 was Grogan’s shining moment: he was a consummate Life Actor (another Bergism) who treated everything he did as a performance, played his role to the full and then burned out. But surely it’s time to honour his memory with a more nuanced view of the San Francisco that was his personal stage.

Ringolevio by Jonathan Myerson is on Radio 4 at 3pm on Sunday August 21 and 28. Also available on BBC Sounds