The Sacred Ritual of Meals with My Mother

A few years ago, when my mother and I were cleaning out my grandparents’ home in Japan, I came across a cache of letters. In them was a document my grandmother had written about her life, from infancy through her marriage and up to the birth of her three children. My mother, the middle child, was born in Japan during the war. My family squatted in an empty house, abandoned because it was near an out-of-commission airstrip still considered a potential target for Americans.

My grandmother wrote of starvation after my mother’s birth. “The doctor told me to give up saving Kazuko, for she is too weak. I became so angry and told myself: ‘I will raise Kazuko to a full grown person.’ In order to prepare Kazuko’s food, I grew rice and spinach and I dried anchovies. I prepared this kind of food for the next two years. She did not walk or sit up during this period. However, suddenly when her second birthday came she stood up and began to walk without anybody’s help. I ordered for her a pair of waraji [rice straw slippers] with red string. When I tied up these slippers on to her feet, Takehiko [my uncle] held her hand and went out to play. They were picking our neighbor’s flowers. When I saw that, I cried with happiness.”

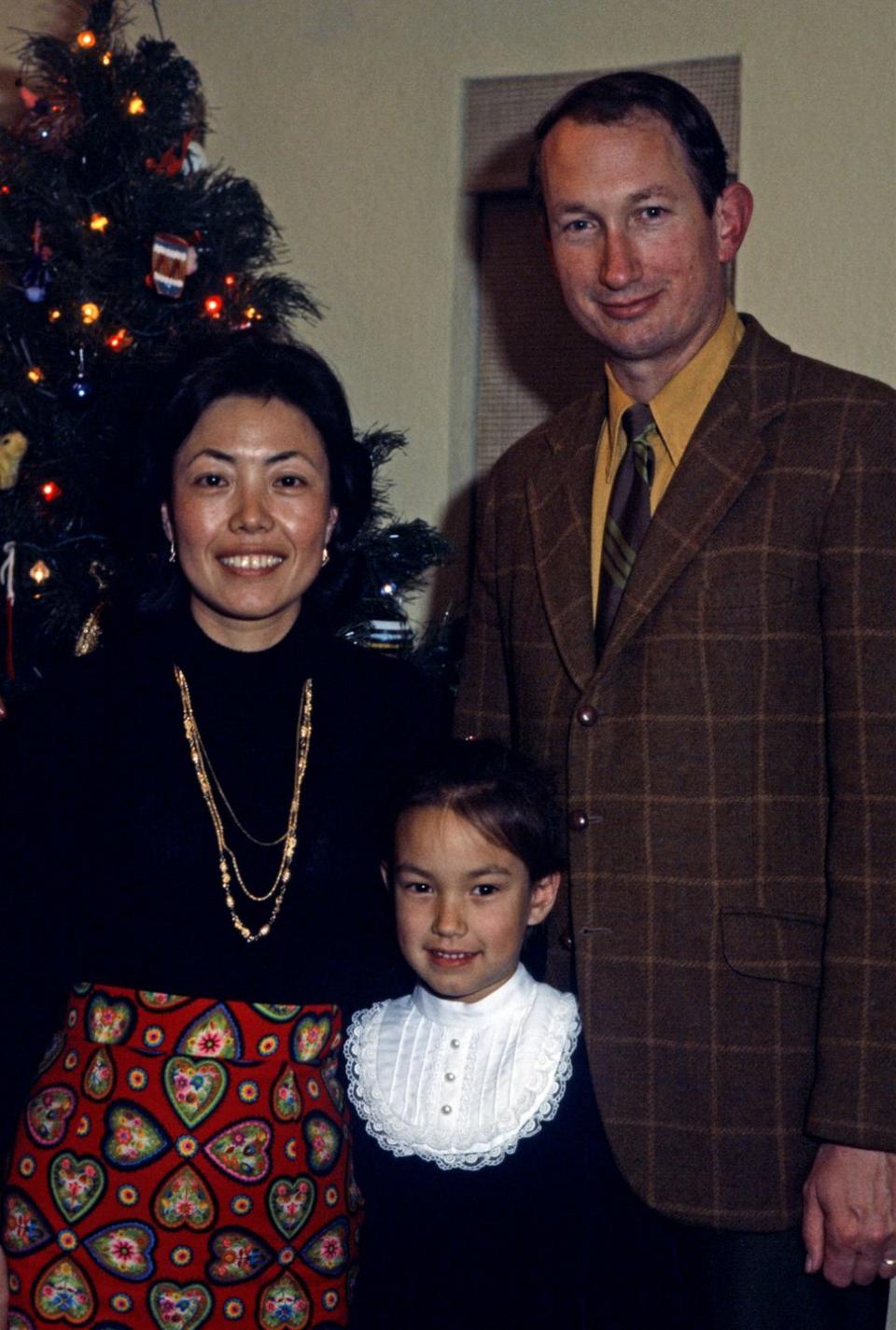

I remembered this passage when I visited the hospital where my mother spent much of last year. She first became sick when I was ten—meningitis—and her health has wavered between fragile and robust for decades. We do not know why exactly. I have always suspected that her birth in a war zone could have exposed her to some toxic concoction of chemicals left over from bombing runs. My family used to tell me about hiding in shelters dug out under rice paddies, and how my grandmother was nearly kicked out when she scampered in with two children. “If the Americans come, they will hear your baby crying!” the townspeople told her. But my grandmother would not leave. To protect her children, she would endure the hate.

Last year, my mother’s health took a severe downturn. I visited her once a week in the hospital, bringing her a flat of sushi. My food was the only food she enjoyed and I fed it to her by hand in a vain attempt to keep her here, though she was steadily losing weight. I thought about my grandmother who fed her to keep her here too.

I had not made the sushi for my mother—it was from Japantown in San Francisco—though I was taught how to make sushi like it. I knew that the carrots were sautéed with soy sauce and dashi. The spinach was steamed, the water squeezed out, and the leaves placed into strips. The egg was whisked and then poured onto a special square pan at a high heat to make a thin and flat omelette. There was the whole matter of seasoning the rice to be neither too sweet nor salty, and of spreading it just-so on a sheet of seaweed without tearing the tissue. Making sushi like this takes hours of assembly—hours which I did and do not have.

“The sishi here is so tiny. You know? Like at Whole Foods?” the nurse said.

“Sushi,” my mother growled.

“Sishi,” the nurse repeated.

“SOO-shee.” My mother took a bite of her food and avoided further eye contact.

In the hospital, I told my mother that it was not necessary to correct the nurse’s pronunciation. She was, I insisted, doing her best.

“I want to go home,” my mother said, referring to the house she has lived in since she moved to America to marry my father, and where he passed away a decade ago. More specifically, she wanted to be surrounded by nature—her rose bed, orchard, and vegetable garden. It was from nature that she learned to forage for wild shoots, insects, and nuts to feed her family in the years after the war, when so many Japanese starved to death. “You give just a little bit to a garden,” she always said, “and it will give back.”

The Japanese believe that whatever you eat in the first three years of your life will dictate your palette forever. There is a very precise way in which children are weaned from breast milk to solid food. First, one eats a kind of rice gruel, which is eventually seasoned with one of two sauces: one made from kelp broth and the other from fish. The first protein is egg white, and the first meat is a salty white fish called shirasu, which is served to adults as a condiment. New mothers are instructed to rinse the shirasu, and I did so religiously when my son started eating solid meat. He didn’t even have a hot dog until he was seven; before that the only protein he wanted was white fish.

My mother followed the same milk-to-rice-to-fish procedure with me. In Japan, it is common for older women to ask mothers: “And does your child eat everything with no likes and dislikes?” To eat everything with joy is considered a virtue.

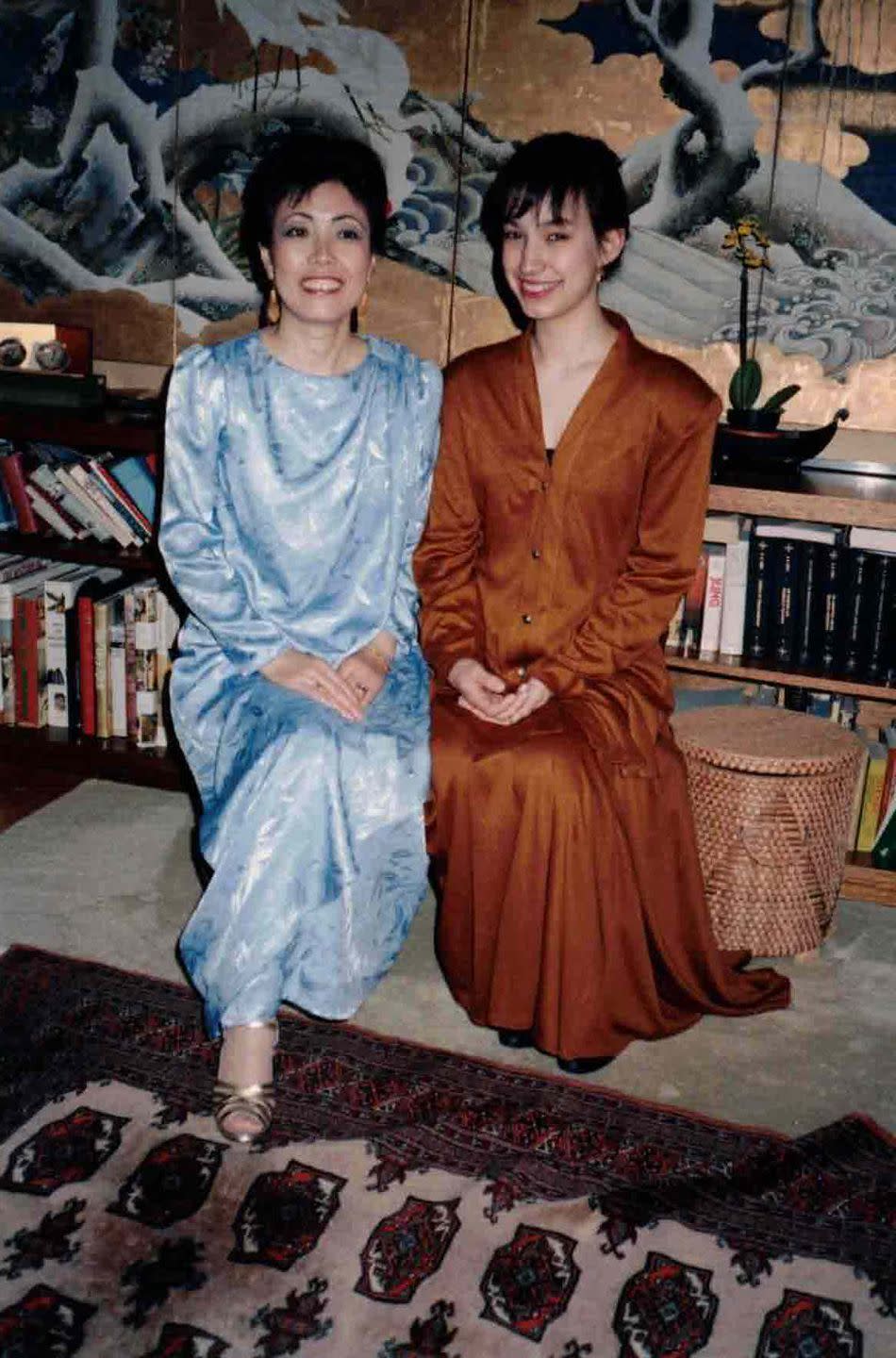

In this, I have failed as a mother. My son, now ten, is picky and argues with me over vegetables, meat, and the thickness of cheese. He has not become a person who “has no likes and dislikes.” My mother and I, on the other hand, are successes; we have shared many meals together, fearlessly eating everything with pleasure and appreciation.

When I was 19, I had pneumonia and was hospitalized for a week. While my fever raged and the antibiotics fought to clear my lungs, I refused to eat. The spaghetti and lasagna cooked up by the hospital kitchen turned my stomach. All I wanted was rice and seaweed: Japanese soul food.

After the final fever broke, my mother arrived with three plastic containers. One had rice. Another held pickled sour plums she had made with fruit grown in her garden. A third held ground beef carefully seasoned. “You’ll get better now,” she grinned as she fed me by hand. And I did. My body reconstituted itself out of her nourishment. Even now, when I am sick, I yearn for those flavors.

Back at the nursing home, before the world shut down to combat a pandemic, the social worker talked to us about how we might plan for my mother’s return home: “You’ll need to either use an assisted living facility, or hire care,” she said to my mother, “That way, you can keep your relationship with your daughter as mother and daughter.” This is what people in the medical field tell the elderly and the dying. It’s a way of suggesting that our bonds with our loved ones should remain purely emotional, as though two people can distill the most important aspects of how they interact, the way cream is spooned out from milk, and leave the rest of the work for others to do. But while it's one thing to accept help with incontinence, bathing, and medication, I stumble over the idea of letting someone else decide what my mother will eat.

Many Japanese homes have an ancestor shrine, with photos of deceased family members, incense, and candles placed next to a statue of the Buddha. After my grandmother died, my grandfather used to put a small bowl of rice and a cup of tea on his altar for her every day. When we had something extra special—a crate of oranges or a rolled sponge cake—these were placed on the altar first so the dead could eat before we did. I used to find these actions beautiful but sort of empty—who really thinks the dead can taste a piece of fruit? Now I’m not so sure.

If you’ve ever played any sport that requires targeting—archery, golf, basketball—you know how accuracy often relies on “follow through.” You cannot just throw, hit, or shoot; you must visualize the follow-through of the object whose trajectory should trace a very specific path. I am beginning to think that leaving food on the altar for the dead is sort of the same thing. Unlike so much in our lives that's now transactional—housework, childcare, store-bought sushi—the making of food is elemental. It makes the cells that constitute the body and keep us clinging to life. I wonder how many problems in the world can be attributed to this lack of understanding: To make food for others from start to finish is to follow through in our commitment to each other.

And yet. Part of the promise of what we call “modernity” is that people (women) need not be yoked to this kind of work—childrearing, cooking, and cleaning—to the exclusion of any other personal striving. And so when a social worker asked me: “Can your mother feed herself?” I understood that the time required for her care was far more than I had to give.

My mother spent two months in the nursing home before COVID-19 struck the West Coast; her facility was among the first to close itself off to visitors in February. Three weeks ago, they began confining residents to their rooms. Now I get a video a day. “I miss you,” she says, her voice slurring, and I wonder if she's been instructed to say this. Sometimes I get a photo of her eating her meals. There is no sushi on her plate.

I text her photos of the vegetables she’d wanted to plant this spring but I did instead—new carrot shoots and “raspberry root” with emerald leaves. Now I understand my mother's implicit faith in the garden and its slow and constant regenerative power. Every day I think, I would give anything to eat a meal together again. I consider removing her from the nursing home and then I ask myself if I am up to the challenge.

If the shoe were on the other foot, my mother would not have left me in a facility, only to see me on the other side of a screen. She would be feeding me. I think of the caretakers and healthcare workers now engaged in “follow through”—caring for others. Their skills, so often under-appreciated in the United States, are now the nightly subject of mass clapping by people trapped at home. But in the countries that have the lowest death and infection rates—countries like South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong and Taiwan—I see the philosophy of follow-through at work, and I wonder if it’s because it’s a skill that was never wholly dismissed from the culture. I wish for a world in which it is our reflex to care for each other in this way, not just during a pandemic or during Mother’s Day, but every day.

You Might Also Like